A recent NASA study outlines possible dedicated missions to the "ice giant' planets Uranus and Neptune.

In 2003, NASA's Galileo mission came to an end by plunging into the atmosphere of Jupiter. Later this year, Cassini will follow suit, ending a decade and a half exploring Saturn and its moons. What's next for planetary exploration? Some researchers are pushing the next logical step: dedicated orbiters for either or both of the "ice giant" outer planets, Uranus and Neptune.

NASA recently released a study outlining just how such a mission (or missions) might unfold. The study is part of a lead up to the next Decadal Survey for 2022–32, a time when planetary scientists prioritize their wish list of future missions. The last Decadal Survey, published by the National Research Council's Space Studies Board, covered opportunities from 2013 through 2022 and offered detailed development studies for the Mars 2020 rover and Europa Clipper missions, though a dedicated Uranus orbiter was in the running as a distant third possibility.

"This study was one of many that will be performed to support the upcoming Decadal Survey deliberations," says Curt Niebur (NASA-HQ). "Once [the next Decadal Survey] is received by NASA, which should occur in 2022, NASA will begin considering which priorities it will pursue and how it will go about implementing them."

To date, only one spacecraft has visited the two outermost planets during its "grand tour" of the outer solar system: Voyager 2, which flew past Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989. But those visits were fleeting, giving planetary scientists brief glimpses of these distant worlds and moons as Voyager 2 headed out of the solar system. An Ice Giant Orbiter would, like Cassini, hang out and explore Uranus or Neptune long term.

Road Trip to the Outer Solar System

But it'll be a long haul, for sure. The problem with outer solar system exploration is, you want a spacecraft moving fast enough to reach its intended destination in a decade or so — but too much speed makes slowing down to enter orbit out of the question. New Horizons was a good case in point, as it took over 9 years to reach Pluto and Charon, whizzing by at 13.8 km per second, with only a hectic flyby period of exploration possible.

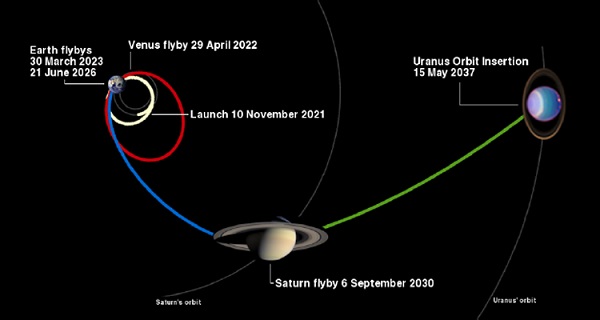

Instead, the mission to either Neptune or Uranus would launch in the 2030—31 time frame, taking 12 to 13 years to reach its target. The study calls for a 50-kg kilogram payload with three main instruments and an atmospheric probe similar to the one Galileo delivered to Jupiter. An "Ice Giant Orbiter" would utilize either traditional chemical propulsion on a slingshot trajectory, or perhaps a new solar-electric propulsion (SEP) system currently in development. Similar to the thrusters aboard NASA's Dawn mission, SEP propulsion offers the ability to maintain low thrust over long periods to build up speed.

NASA / JHU-APL

The study notes that an optimal window for a Uranus mission using a gravitational flyby assist of Jupiter exists in 2030 to 2034, while the same window for a Neptune mission runs from 2029 to 2030. Getting an orbiter to Uranus via an assist from Saturn could be carried out prior to 2028.

NASA/ CSA

An Ice Giant Orbiter would be a $2 billion "Flagship mission, the top end of what NASA flies for planetary exploration. Other Flagship alumni included Cassini and the Mars rover Curiosity. Other classes of NASA missions include mid-range ($500 million to $1 billion) New Frontiers missions such as Juno and OSIRIS-Rex and less-than-$500-million Discovery missions such as Lunar Prospector or Mercury's Messenger.

Scientists proposed a dedicated return to Uranus and Neptune early in the development of New Horizons. Such a “New Horizons 2” mission would've been a clone of the original, but it was later dropped from the program due to cost constraints.

Prime objectives for either mission would include a study of the planet's atmosphere, interior, and ring system as well as a survey of major moons and a hunt for more. Neptune's large, strange retrograde moon Triton is of particular interest, as researchers believe it's a captured Kuiper Belt object (KBO). At a minimum, an Ice Giant Orbiter mission would carry a mass spectrometer, wide and narrow angle cameras, a magnetometer and dust sensors.

NASA / Hubble / ESA

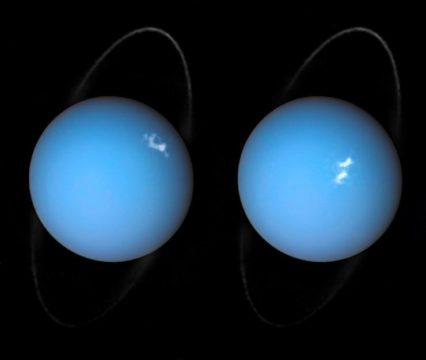

Uranus in particular would offer a challenging target, as the planet rotates tipped on one side. When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, its southern hemisphere was in the middle of a 21-year-long summer and its northern latitudes lay hidden in shadow. A future spacecraft would arrive with the seasons reversed.

"The quick look we got from the Voyager 2 flybys of Uranus and Neptune taught us many things, but critical mysteries remain," says Mark Hofstadter (NASA/JPL). Compared to rocky terrestrial worlds or gas giants, ice-laden planets seem to be in a class by themselves. "Another important thing about Uranus and Neptune is that they seem similar to most of the exoplanets we are discovering around other stars," Hofstadter says. "To understand those distant planetary systems, we need to understand two examples that we can actually visit."

Planetary missions can provide a wealth of science discoveries for decades to come. For example, Georgia Institute of Technology researchers recently announced the magnetosphere of Uranus behaves like a light switch — a discovery that utilized Voyager 2 data gathered more than three decades ago.

NASA/KSC

As with every outer solar system mission to Saturn and beyond, an Ice Giant Orbiter would be equipped with a plutonium-fueled Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) for power far from the Sun. NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy announced in 2016 that the latter would restart the production of Pu-238 (a different isotope than the fissile Pu-239 used in nuclear weapons) for space exploration, and this exotic cache should be available in the 2020s for space exploration. NASA also elected to halt development of an Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generator (ASRG) engine in 2013, which would've been four times as efficient as traditional RTGs. That tough decision was due to budget cuts, though the study anticipates enhanced eMMRTGs and a Heatshield for Extreme Entry and Environment Technology (HEEET) to be available for an ice-giant mission in the late 2020s.

This idea comes at an exciting time of crisis and opportunity for NASA and solar system exploration. On one hand, our eyes in the outer solar system are going dark, as Juno, Cassini, and Dawn all finish up their respective missions. NASA also seems to currently favor selecting smaller, low-cost missions such as Mars InSight, Lucy, and Psyche — perhaps in an effort to assure all of its “eggs aren't in one basket,” as opposed large expensive missions that might look attractive to the financial axe.

And perhaps, long mission timelines extending out to the 2040s are a bit depressing to children of the Apollo era... weren't we supposed to be vacationing on Mars by 2017?

Remarkably, interplanetary missions that could run through the midway point for this century are now under serious consideration.

6

6

Comments

Robert-Casey

June 30, 2017 at 9:55 am

Maybe doing a gravity assist flyby of Neptune's moon Triton could help a probe get into orbit around Neptune, coupled with smaller retrorockets? Uranus' moons are probably too small to help a Uranus probe here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mjmorri

June 30, 2017 at 2:33 pm

For the first time in my life NASA is starting to propose missions whose years of conclusion may exceed my own.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Myth

June 30, 2017 at 8:34 pm

I highly doubt a cure for cancer will be found on Uranus....

I personally think finding a cure for saving the planet is more important than building expensive toys for narcissists who don't want to teach anymore. Let's try working on cutting down on the world's population, conserving and properly using our natural resources, finding a CURE for cancer and not a symptom relief approach to it, finding a way to relieve mankind of his fascination with killing (war) each other, and on and on and on.

If we don't work on these more pressing matters FIRST....then 2030 may never get here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

richard_malcolm

July 1, 2017 at 5:02 pm

A cure for cancer won't be found at Uranus. But that doesn't mean that we can't learn a great deal about the Earth, how it was formed, and how it is affected by its spatial environment by exploring other parts of the Solar System.

The $2 billion cost of a flagship mission to Uranus or Neptune isn't even a rounding error in the cost of addressing cancer, or climate change, or any other major problem on Earth - and we will *always* have problems on Earth. The United States, and humankind generally, can walk and chew gum at the same time; it can conduct robotic exploration of the rest of the universe on a (very) modest scale while trying to improve life here at the same time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

philip-gardner

July 3, 2017 at 7:00 am

We should strive to achieve the highest ideal we can, if that means going to a gas giant, I'm all for it. The magical "cure for cancer" is a myth because it supposes it is one disease and it is not. It is a complex range of diseases. The technological advances achieved by solving the problems with space travel, have, over the years, paid back enormously, in improvements to human lives across the planet, including advances in health. The space station is a prime example of where research into living in a totally hostile human environment has direct counterparts in medical uses on earth, e.g. robotic manipulators in the operating theatres. Space travel! what better way to distract us from killing each other.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

July 10, 2017 at 4:06 pm

I know I'm way ahead of the bureaucratic process, but let's assume one of these missions get funded -- or heck, let's imagine they both get funded! Obviously the Uranus mission should be named Herschel, despite the possible confusion with the infrared space telescope of the same name. And the Neptune Mission would be Le Verrier, with the lander Galle. Sorry, but Adams doesn't make the cut.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.