Last October 25th, I slept in a meteorite crater. The largest meteorite crater in the world, to be sure. So large, in fact, that it’s almost impossible to recognize it for what it is. Many people living in the small town of Vredefort don’t even know that their house is built at the site of a cosmic catastrophe.

Southern Africa is a fascinating part of the world, containing many astronomical highlights. It hosts the largest optical telescope in the Southern Hemisphere (the 11-meter Southern African Large Telescope or SALT) and it will be home to the mid-frequency part of the largest radio observatory in history (the Square Kilometre Array or SKA), both of which I described in a previous travel blog.

Govert Schilling

But this part of the world is also a paradise for cosmic impact aficionados. For starters, here you will find the largest meteorite known, weighing in at over 60 tons. It’s hard to miss: just west of Grootfontein, Namibia, there’s a large turnoff sign on highway B8 saying “Meteorite”. The gravel road takes you to the Hoba West farm, where the giant slab of iron and nickel, measuring some 2.7 meters across, lies at the center of a small artificial amphitheater.

Why would anyone choose this remote site to display the largest meteorite on the planet? Easy: because it fell here, some 75,000 years ago, and it has never been moved since. (The space rock was accidentally found by a ploughing farmer back in 1920.)

“It’s worth a quick stop only,” says my Lonely Planet guide for Namibia, “and its size is not all that impressive.” I strongly disagree. I know the Hoba meteorite from magazine articles and photos, but walking around the cosmic visitor and touching its many eroded thumbprints (officially known as regmaglypts), as I did on November 9th, is a great experience. This thing is huge!

Govert Schilling

About a week later and much further south, I run my fingers over some of the remnants of a more recent meteorite fall. A massive iron object encountered Earth some 30,000 years ago, and exploded high in the atmosphere. Its fragments were strewn across a 20,000 km2 area. Since the mid-1970’s, some 30 large chunks of the Gibeon iron meteorite have been on display at Post Street Mall in downtown Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city.

Govert Schilling

Scars and Bruises

S&T: Monica Young / source: Govert Schilling

Southern Africa is a very old part of our planet’s crust, so it’s not too surprising that meteorites from prehistoric times have been found and collected here. It’s also the reason that the area contains a number of ancient impact craters — cosmic scars and bruises you won’t readily find in geologically younger regions.

There’s one problem, though: old meteorite craters may be very hard to recognize as such. Arizona’s Meteor Crater, east of Flagstaff, has a well-preserved bowl shape, partly because of its relative youth of some 50,000 years. Older craters, however, may suffer from slow geologic processes and erosional forces. In many cases, the original crater has become filled up with younger deposits, while the crater’s rim has eroded away.

That fate befell the South African Kalkkop crater, some 40 kilometers south of the town of Graaff-Reinet. Despite a detailed road atlas and a GPS, I find it hard to locate the crater, on one of the first days of my six-week trek through South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia. It’s not a tourist attraction at all; there are no road signs, and it appears hardly anyone has ever heard of it.

Govert Schilling

Bumpy dirt roads eventually take me to a roughly circular area of broken pieces of limestone, a few hundred meters across. The limestone has been deposited over the past 250,000 years or so by draining water; below is a thick layer of fragmented rock. Only a trained geologist’s eye would be able to identify this site as an impact crater.

With the 1.1-km Tswaing crater, just north of the bustling metropolis of Pretoria, it’s much easier. Although it’s about the same age as Kalkkop — the crater was excavated 200,000 years ago or so by a stony meteorite some 40 meters across — it has been much better preserved. In fact, with a depth of some 100 meters, Tswaing is quite comparable to Meteor Crater. The big difference: its walls are covered by vegetation and it has a huge lake at the center.

Govert Schilling

Tswaing is a tourist destination, with a parking lot, a small exhibit, and a ticket counter. But in late October, I’m the only visitor. A hiking track takes me all the way around the crater rim and even down to the lakeshore. It’s a pretty tough walk: temperatures soar close to 100°F. The area harbors many ruined remains of old industrial buildings and facilities — for centuries, people have been mining salt and sodium here. Interestingly, the impact nature of the crater wasn’t confirmed until 1990.

Too Big to Fathom

Júlio Reis / NASA

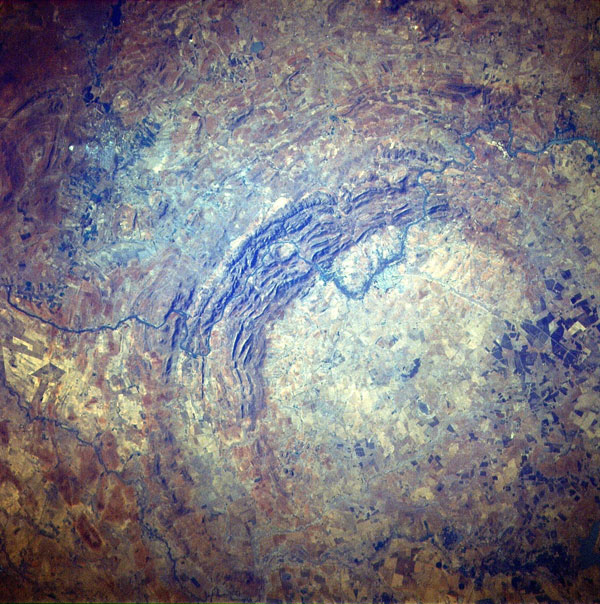

No one is allowed to spend the night in the Tswaing crater. But it’s impossible to impose that rule on the Vredefort crater, centered at a point some 200 km south-southwest of Tswaing. In fact, the city of Johannesburg, with a population of over 4 million, lies just within the original confines of the crater. Formed more than 2 billion years ago by the impact of a city-sized asteroid, Vredefort originally measured some 300 km across. It’s just too big for human beings to fathom.

Even from the air or from space, the multi-ringed impact crater is hard to recognize. From the ground, it’s all but impossible. The small towns of Vredefort, Parys, and Koppies lie close to the granite dome that marks the crater’s central uplift — a large group of mountains that can be seen from a distance of tens of kilometers.

That night, I park my truck at a small camping site on the south bank of the Vaal River, just north of Vredefort. Lying in my rooftop tent, I admire the serene view of the stars rising above the distant hills. It’s incredibly quiet. I try to imagine how the surrounding area must have looked two billion years ago, when the asteroid struck out of the blue. Back then, Earth’s surface was still barren and lifeless, but, even so, a peaceful day suddenly turned into a cosmic Armageddon.

Govert Schilling

I know there’s currently no threat of yet another 15-km-diameter asteroid colliding with Earth. Even impacts of huge space rocks like the Hoba Meteorite are pretty rare. No need to worry. Still, as I turn on my side in my sleeping bag to catch some night’s rest, I realize that I’m not just a traveler on Earth. I’m road tripping space itself. It’s a good thing to be aware of the other traffic.

4

4

Comments

Stub Mandrel

May 19, 2017 at 4:22 pm

Great article, I would love to visit Namibia some day - amazing dark skies, wildlife and rare plants!

Stub.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mattperson

May 19, 2017 at 8:37 pm

How big is the Berringer Meteorite? I would think it bigger than the Hoba Meteorite, or is it that it is still buried?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

May 22, 2017 at 5:17 pm

Most of it was vaporised in the impact, but plenty of fragments have been recovered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

darkchairman

May 30, 2017 at 8:26 pm

Is the Congo basin a meteor crater? On the Rand McNally geo-physical world map the basin appears round, similar to the Argyre Planitia on the Mars globe. A near-circle is formed by the Congo River around the north and east, Lac Ntomba and Lake Mai-Ndombe on the west, and the Kasai-Sankuru-Lubefu River on the south. Salonga National Park is near the center. The circle is about 850 km across.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.