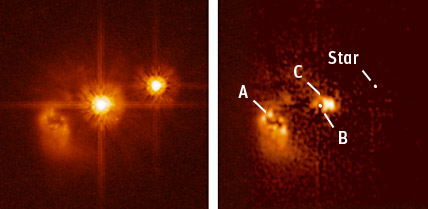

Left: The Hubble Space Telescope captured this view, just 7 arcseconds wide, of HE0450–2958, a quasar 5 billion light-years distant in the constellation Caelum. Right: Mathematically removing most of the quasar's starlike glow enhanced the view of a neighboring galaxy (A), and it should have revealed a host galaxy surrounding the quasar (B). But it only revealed a lopsided blob of gas (C) that is entirely devoid of stars.

Courtesy NASA, ESA, and Pierre Magain (University of Liege, Belgium).

Discovered four decades ago, quasars are starlike pinpricks of light that shine across billions of light-years of intergalactic space. Conventional wisdom states that they

are the ultracompact, ultraluminous nuclei of massive galaxies. The Hubble Space Telescope has amply buttressed that paradigm, showing that most of these ultraluminous beacons do inhabit recognizable galaxies. But a new Hubble study of 20 relatively nearby quasars in today's issue of Nature has turned up one that apparently is galaxy-free.

And that poses a puzzle. After all, astronomers have concluded that a quasar lights up because a supermassive black hole in a galaxy's very core has gobbled up nearby material, heating some to multimillion-degree temperatures and blasting the rest into space at near-light speeds. If HE0450–2958 truly lives in intergalactic space, then astronomers have to explain where it gets its fuel.

One piece to the puzzle may be the unusual galaxy that lies to the southeast of the ostensibly "naked" quasar. That distorted galaxy reminds astronomer Georges Meylan (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne) of "The Antennae" (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), a relatively nearby pair of colliding galaxies in Corvus. HE0450–2958 "may be a case where the original host galaxy, if there was one, was disturbed by a dynamical encounter" with the neighboring galaxy, says Meylan.

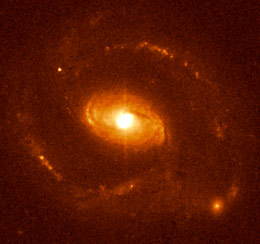

That Hubble is capable of detecting a quasar's host galaxy is evidenced by this image of HE1239–2426, 1.5 billion light-years from Earth on the Hydra-Corvus border. This quasar — presumably a supermassive black hole whose gravity accelerates surrounding matter to near-light speeds — is surrounded by a recognizable spiral galaxy.

Courtesy NASA, ESA, and Pierre Magain (University of Liege, Belgium).

Meylan, lead author Pierre Magain (University of Liege, Belgium), and their colleagues "do seem to have done the analysis carefully" in today's Nature paper, says University of Arizona quasar expert Jill Bechtold — an important consideration when the analysis involves mathematically removing the quasar's far brighter light to look for details that even Hubble can only barely resolve. But that doesn't necessarily mean that HE0450–2958 is a homeless black hole, says longtime quasar observer George Djorgovski (Caltech). "Much of the host may be obscured by dust," he notes, as sometimes is the case for the host galaxies of distant gamma-ray bursts. Alternatively, the host could be a so-called low-surface-brightness galaxy — a distant analog of the large but diffuse spirals that astronomers discovered in our cosmic backyard only recently. At HE0450–2958's considerable distance, a spread-out spiral host wouldn't register even on Hubble's sensitive detectors.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.