New images from the European Space Agency’s Venus Express orbiter hint there might be active volcanoes on Venus today.

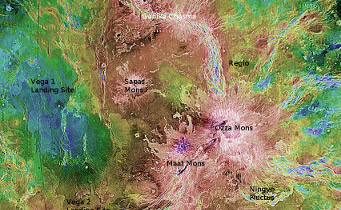

NASA / S&T: Gregg Dinderman

Despite being the closest planet to Earth, Venus remains enshrouded in a cloud of mystery — both figuratively and literally as it’s covered by thick skies of carbon dioxide and even clouds of sulfuric acid — making it extremely difficult to view the planet’s surface.

We do know that while Venus is nearly Earth’s twin in mass and size, the planet is entirely foreign, even deadly. The atmospheric surface pressure is 93 times that on Earth, and the temperature is almost 900° Fahrenheit. Its surface is dotted with more than 1,000 volcanoes, rising from smooth plains indicating past lava flows.

But are volcanoes still active on Venus today?

This question has been a hot topic within the scientific community for decades. Both NASA’s Pioneer Venus and ESA’s Venus Express orbiters recorded a significant increase in the average density of sulfur dioxide — a gas commonly known for being produced by active volcanoes on Earth — in the upper atmosphere. In both cases the signature was immediately followed by a sharp decrease, likely because the molecule was broken down by sunlight.

But the presence of sulfur dioxide in Venus’s upper atmosphere isn’t the only clue pointing to volcanism in the planet’s recent geological past. In 2010, Suzanne Smrekar (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) and colleagues spotted former lava flows on the planet’s broiling surface. The team analyzed images from the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS), onboard the Venus Express orbiter, which can see through the thick clouds and measure the brightness of surface rocks. They detected nine locations that emit abnormally high amounts of heat when compared to their surroundings.

Further analysis compared the hot spots to terrestrial hot spots such as Hawaii, which are believed to overlie mantle plumes and therefore indicate current volcanic activity. Ultimately the team concluded that three of their candidates were geologically young lava flows, less than 2½ million years old.

While multiple detections have pointed toward active volcanism in the planet’s recent geologic past, there is no direct evidence for ongoing volcanism today.

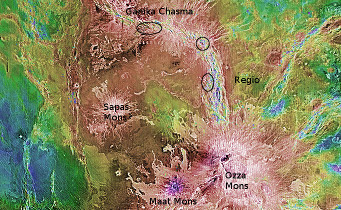

New surface images, however, show three transient bright spots at the edge of a young rift zone known as Ganiki Chasma. The new data, presented by Eugene Shalygin (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research) and colleagues at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston on March 17th, are thought to be eruptions that occurred late last year.

NASA / S&T: Gregg Dinderman

The team took 36 separate images of a region surrounding Maat Mons — a giant shield volcano that scientists think erupted 10 to 20 million years ago — using the Venus Monitoring Camera (VMS). It has a near-infrared filter (1.01 micron) at which the atmosphere is largely transparent, so images taken of the planet’s night side at that wavelength can map heat coming from the Venusian landscape.

If the spots are really hot spots on or near the surface, the team estimates them to be 980° to 1,520° Fahrenheit, well above the planet’s typical balmy temperature of 800° Fahrenheit.

But could the hot spots be illusory? The team considered whether they were seeing smudges on the VMS optics and “holes” in the clouds but eventually rejected both theories. Instead the bright spots are an “indication of some localized process that releases hot matter,” writes Eugene Shalygin (Max-Planck Institute) in the conference preceding.

Shalygin and colleagues suggest the hot matter could be ongoing lava flows stretching 16 miles or so, a chain of cinder cones, or volcanic hot spots. Any of which would make these observations the very first images of active volcanic processes on Venus today.

So far the claim has not been confirmed. There's no evidence of past lava flows in this area and there is a 3-month gap in coverage after the features were spotted. So it's unclear how long these hot spots may have persisted. Shalygin’s team plans to sift through archived radar images from NASA’s Magellan spacecraft, which visited the planet from 1990 to 1994, and look for similar hot spots in other rift zones using the Venus Express spacecraft.

Shalygin preferred not to comment on the team’s findings until his team's research is officially published in Nature.

4

4

Comments

Dennis

March 24, 2014 at 4:25 pm

One would believe if there were true then Venus's interior would generate a similar dynamo effect that would produce a magnetic field. That doesn't appear to be the case though.

Thoughts?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Alson Wong

March 24, 2014 at 9:10 pm

Venus rotates very slowly (once every 243 days), which is too slow to generate a dynamo effect,

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John Cudworth

March 27, 2014 at 10:38 am

Is the 900 degree F. temperature just because of the runaway greenhouse effect? Could the heat also be caused by hot lava coming up out of the interior ( and the atmosphere trapping that heat under there? ) Has anyone done a computer thermal simulation of this?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew R Brown

March 29, 2014 at 7:52 am

I wonder if the core of Venus is not as hot as Earth's? Also Venus appears to have a singular solid core with a molten lower mantle, unlike Earth and Mercury which both have a solid inner core and a molten outer core which is convecting.

This is a huge difference between the Earth and Venus and would certainly explain the lack of a magnetosphere.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.