In 2008, while in London, I made a point to see what had become of the city's once-famous planetarium. It had closed two years earlier, only to become part of Madame Tussaud's waxworks.

A sorry sight: London's main planetarium is now part of Madame Tussaud's entertainment complex.

J. Kelly Beatty

Today the huge dome boasts an action-packed "experience" that, among other things, explores how Marilyn Monroe and other celebrities are viewed by aliens. I am not making this up.

But a shuttered star theater isn't always bad news. A year ago Boston's Charles Hayden Planetarium closed for a promised $9 million physical and technological transformation — and I'm happy to report that its doors have once again opened wide to the public. New England's preeminent star dome, whose 57-foot diameter is nearly equal to London's, now can razzle and dazzle as well as any planetarium in the world.

The much-needed renovation was supposed to be unveiled two years ago (and had been on the drawing board for a decade) but stalled partly for lack of funding and partly due to the departure of planetarium director Robin Symonds. The void at the top was filled by David Rabkin, the museum's director of current science and technology. "We felt our team was strong, and I had a strong relationship with them," he explains. "So why screw it up?"

Opened in 1958, the Charles Hayden Planetarium (white dome at right) at Boston's Museum of Science has attracted more than 11 million visitors.

J. Kelly Beatty

Even with funding secured, the technological tasks were formidable. The clear trend among big-city planetariums (or planetaria, depending on your taste) has been to junk all the banks of Kodak slide carousels in favor of full-dome digital projection. It's immersive, to be sure, but not always a true-sky experience. The full-dome digital systems rolled out during the 1990s were hindered by fuzzy stars and often-ragged video.

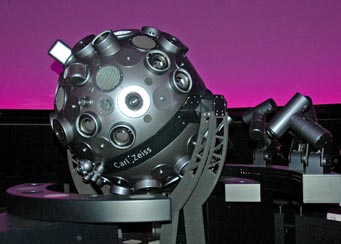

Rabkin and Hayden's staff avoided incurring the wrath of planetarium purists by marrying a state-of-the-art Zeiss Starmaster projector, imported from Germany, with a crisp 16-megapixel digital video system, imported from Sky-Skan in neighboring New Hampshire. One of only two in the U.S., the Zeiss's burnished-metal orb uses fiber-optic technology to fire 9,100 razor-sharp pinpoints onto the newly resurfaced dome. Trust me, it creates a 6½-magnitude sky so real that you'll be tempted to bring your binoculars along for a closer look.

My first question was: "What took you so long?" According to Mark Petersen of Loch Ness Productions, an independent producer of planetarium shows, nearly 700 sky theaters worldwide already offer full-dome video, not counting the ones with tilted or portable screens.

An audience at the newly transformed Charles Hayden Planetarium in Boston is immersed in a full-dome video presentation.

Museum of Science / Michael Malyszko

"Full-dome video projection of computer graphics is the only game in town these days," Petersen explains. "Boston — and indeed any planetarium wanting to do more than project stars and point out constellations — has no choice but to adopt it, or go the way of the dinosaurs."

Several Sky & Telescope editors attended Hayden's celebrity-studded grand reopening last week, which featured the debut of "Undiscovered Worlds." Written in part by physicist-author Alan Lightman, and drawing on local planet-hunters Lisa Kaltenegger and David Charbonneau from Harvard and Sara Seager from MIT, the 30-minute-long program explores the hows, whys, and wows of searching for other solar systems.

As producer Danielle Khoury LeBlanc explains, "We chose exoplanets because of its timeliness, because it's an exciting topic, and because it lends itself so well to the dome's 360° environment."

Costing $2 million, the Zeiss Starmaster installed at Boston's Charles Hayden Planetarium uses fiber optics and its lens-covered 30-inch ball to project up to 9,100 stars. Cylindrical projectors at right display the positions of solar-system objects up to 10,000 years in the past or future.

J. Kelly Beatty

Flashing my colorful "boarding pass" (ticket) and entering the 209-seat theater, I saw familiar surroundings: in the center stands the Zeiss Starmaster, a lens-covered ball with a passing similarity to the Death Star spaceship from Star Wars. Off to one side of the vaulted theater is the 10-foot-wide control panel, which glows with complex computer displays. Unseen on opposite sides of the dome are two Sony video projectors that fill the sky with dramatic video. "It's got eight times the definition of your wide-screen TV," boasts animator-visualizer Chuck Wilcox.

| Click here to hear or download a 5-minute interview about the planetarium's capabilities with Chuck Wilcox. |

New visitor displays are part of the Boston Museum of Science's $9 million renovation of its Hayden Planetarium, which reopened in February 2011.

J. Kelly Beatty

So what's next? No one would tell me, but the Hayden staff is committed to producing its own presentations and distributing them widely — one of only a handful of U.S. planetariums to attempt full in-house production. "We have a challenge to top what we've just done," Rabkin admits. "But the team will tell you, "We can't wait to do the next show.'"

3

3

Comments

Tony Flanders

February 18, 2011 at 7:27 am

Like Kelly, I was at the premier show. What really impressed me wasn't the technology, but the show itself. Gee-whiz technology all too often becomes a substitute for substance, but not in this case. The show really conveyed the importance and excitement of the exoplanet hunt -- but that's the easy part. It also presented all the important scientific information thoroughly, accurately, and at a level that any lay person could understand with ease. All of this without being at all boring or didactic. That's quite a trick!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

February 18, 2011 at 3:26 pm

I'm happy to hear that the Boston Hayden Planetarium turned out so well. The Morrison Planetarium in the recently rebuilt San Francisco Academy of Sciences uses state of the art computerized video projection, but doesn't have an optical star projector. I miss the old projector, which was built with Army surplus artillery equipment. The video shows in the new planetarium are exciting and informative, but I still believe that the primary purpose of a planetarium is to teach visitors about the visible night sky, and nothing does that like an optical projector. I guess that belief means I'm going the way of the dinosaurs. Oh well, so are we all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David Fried

March 4, 2011 at 8:29 pm

Last Saturday I went to check out "The Sky Tonight" show, because I was most interested in how the new Zeiss Starmaster handled the traditional night sky. The chairs were terrific; the show, less so, although the children in the audience seemed both enthusiastic and knowledgeable as they shouted out answers.

The projection was very good, but I certainly did not see a quantum advance on the traditional Zeiss projectors. The low profile of the new projector, compared to the giant whirling dumbbells of the old, was a great improvement.

What disappointed me was a failure to relate what the audience was seeing to the real, light-polluted sky they might see from their backyards. This was a lost opportunity to point out just how far most people would have to travel to see anything like the projected sky, and what we might do about it. Ironically, for the first half of the show the presenter forgot to turn off the "Exit" signs, spoiling everyone's dark adaptation. The difference when she turned them off was a "teachable moment" that she failed to seize upon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.