It must be hard to design a spacecraft. When you send a robotic explorer to study an unknown world, you need to plan for everything because you never know what you'll find.

In November 2005, the Cassini spacecraft looked back toward Saturn's icy moon Enceladus and caught its profile backlit by sunlight. Several volcanic plumes tower above the 500-km-wide satellite. Their spray fills Saturn's E ring with icy particles that ultimately coat many of the planet's other satellites.

Kelly Beatty

Take NASA's Cassini orbiter, for example. Back in 1997 when the spacecraft left Earth and headed out to Saturn, who would have guessed that, a decade later, mission scientists would be flying it through an ice volcano's plume?

On March 12th, Cassini did just that, making a super-close flyby of Saturn's moon Enceladus and peering down onto the enigmatic "tiger stripes" in the moon's southern hemisphere from just 50 km (30 miles) above the surface. These stripes, discovered in 2005, are warmer than any other place on Enceladus and are home to the geysers.

Fortunately, the Cassini designers had planned for everything — or at least for enough things. They had the craft's cameras snapping pictures, a spectrometer measuring ejecta composition, and a dust analyzer poised to analyze the particles coming off the surface.

In concert, scientists planed to use these instruments to "dissect" the plume. They wanted to know what powers the volcanoes, they wanted to know if the gases in the plume match those that are found in the halo of bits around Enceladus, and they wanted to learn more about the size, make-up, and speed of the particles coming from the surface. Their ultimate goal is to learn how the geysers formed in the first place.

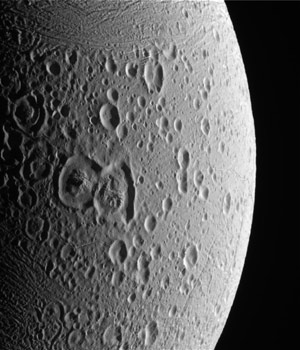

This image from Cassini's March 12th flyby shows details at 190 meters per pixel.

NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Unfortunately, a software glitch knocked out the dust analyzer when Cassini was at closest approach. But everything else worked beautifully. Just take a glance at raw images that were beamed back to Earth late last week. Certainly these are just a taste of things to come.

So far the team has pinned down that geysers are shooting out water vapor at around 400 meters per second (900 mph). Check out NASA's press release for more details.

It's hard to believe, but Cassini's four-year-long primary mission is coming to a close in June. But not to worry: an extended mission is planned, funded, and ready to go. Among the first major highlights will be a return to Enceladus on October 9th to again study what's in those geysers.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.