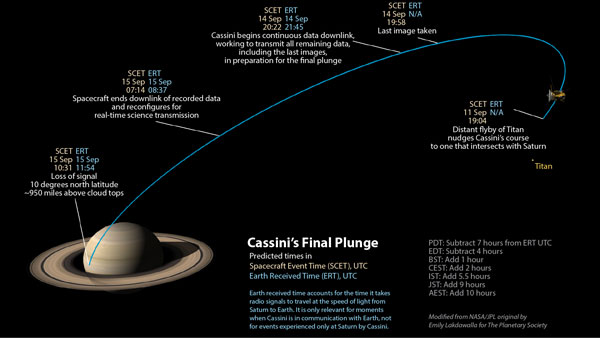

At 7:55 a.m. EDT on September 15th, we will officially observe a loss of signal from the Cassini spacecraft as it makes its fateful plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere, traveling at 76,000 mph (34 kilometers per second).

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Emily Lakdawalla

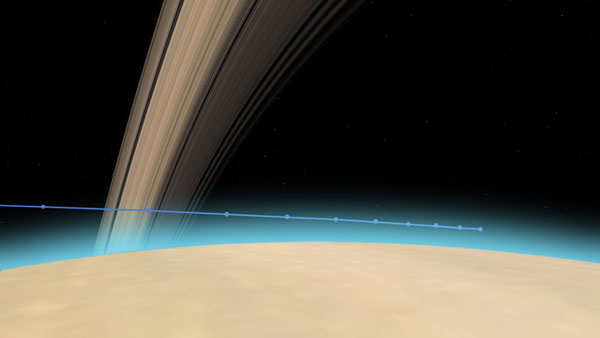

During the orbiter’s last moments, its control thrusters will fire at 100% of their capacity in order to keep the high-gain antenna pointed toward Earth. This will enable the spacecraft to send any last remnants of invaluable data our way before the spacecraft itself becomes a meteor high above the clouds of the ringed planet. The team has predicted loss of communication at an altitude of about 1,500 kilometers (930 miles).

NASA / JPL-Caltech

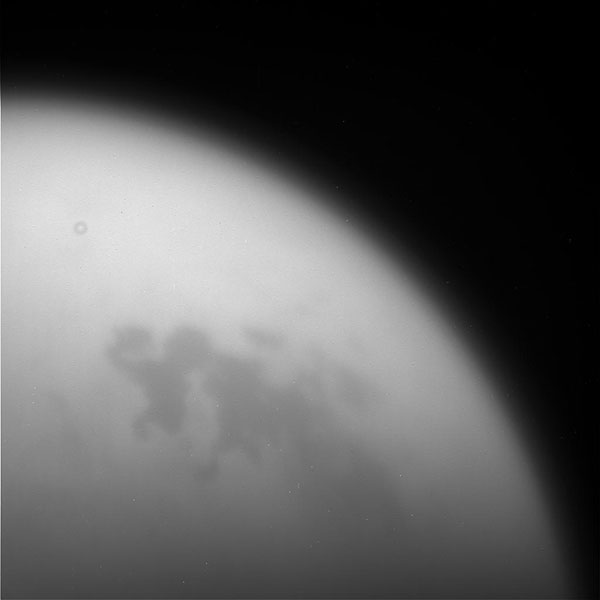

The discoveries made by Cassini during its 13-year exploration of the Saturn system are vast. Liquid methane seas and lakes of Titan, and the liquid water world of Enceladus, complete with its geysers and possible hydrothermic vents are only some of the major discoveries the probe has unveiled.

“The possibility of life so far from the Sun has opened up our paradigm of where you might look for life,” said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker (JPL), “both within our own solar system and in the exoplanet solar systems beyond.”

Titan’s “Goodbye Kiss”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

At a distance of 84,000 kilometers on the morning of September 11th, Titan’s gravity nudged Cassini one last time, removing 39 meters per second from the spacecraft’s velocity and sending it on its inevitable collision course with Saturn.

Earl Maize, Cassini project manager, explained how Titan acted as a main engine to the orbiter, making 127 major course changes possible during a total of 294 orbits.

“Titan gave us one last little nudge back in April, and pushed the Cassini spacecraft between the rings and the planet itself,” he said. That change began the sequence of 22 grand finale orbits. “Every time we fly by Titan, we get a little bit better view of Titan and a little bit better view of the Saturn system.”

The Final Plunge: What to Expect

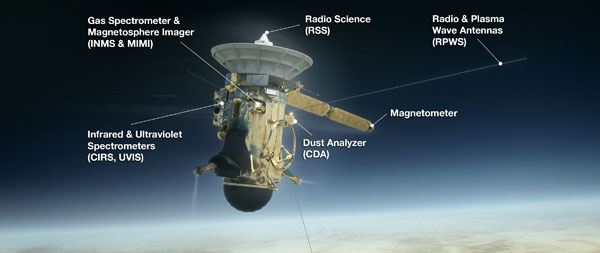

“We have an extensive set of science objectives that we’re going to execute on this final plunge,” said Hunter Waite (South West Research Institute), who acts as team lead for the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer. “We’ll be able to make the cleanest sample of the atmosphere of Saturn itself.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech

One of the most important issues scientists are trying to figure out is a concept called ring rain. Scientists introduced the concept in the 1980s to explain Pioneer and Voyager observations of water vapor and ice grains coming from Saturn’s rings that fall into and change the planet’s atmosphere.

“Well, as Cassini has always delivered, ring rain is much more extensive than that. It’s much more complicated. We’re getting great new data,” said Waite, “and trying to find out exactly what’s coming from the rings and what is due to the atmosphere, and that final plunge will allow us to do that.”

Another objective, as Cassini moves closer to the thicker atmosphere, is to get a better idea of the hydrogen to helium ratio. “This is important in terms of the formation of and evolution of Saturn itself,” Waite adds.

More Questions than Answers

Pauline Acalin

Spilker, who also worked on the Voyager mission, divulged that scientists have been examining data from Cassini’s grand finale orbits and finding that many of their models are either too simple or just out-and-out wrong.

“In particular, the interior of the planet is very different than we expected,” Spilker said. The ringed planet’s almost perfectly aligned magnetic field presents another puzzle. “Everything we think we know tells us that if you don’t have at least a small tilt, you can’t maintain those currents that sustain a magnetic field. So we have some more thinking and some more work to do.”

“We set out to do something at Saturn. We did it. We did it extremely well,” said Cassini project manager Earl Maize. “And we left the world informed, but still wondering.”

Cassini's Goodbye

Pauline Acalin

On Sept 14th, the Deep Space Network (DSN) will begin down-linking Cassini’s last data at 5:45 p.m. EDT (21:45 UT), initially at Goldstone and then continuing at Canberra at 11:15 p.m. EDT (3:15 UT, Sept 15).

The very last image Cassini will take will be the location of its own demise. According to Linda Spilker, the image will be dark, as it will be taken on Saturn’s night side.

“We are here at a very historic time, but it really started with the Voyagers passing through the Saturn system begging us to go back,” said Jim Green, director of planetary science, as he acknowledged the full-scale Voyager display in NASA/JPL’s press room.

As Carl Sagan wrote in the very first issue of The Planetary Report titled Approach To Saturn, “By examining other worlds – their weather, their climate, their geology, their organic chemistry, the possibility of life – we calibrate our own world. We learn better how to understand and control the Earth.”

Just as Voyager is still bringing us new science, we should expect the same from Cassini for decades to come.

2

2

Comments

Graham-Wolf

September 14, 2017 at 10:41 pm

The Cassini MIssion....

13 wonderful years.

Immeasurable quantities of valuable data.

A host of awesome images.

We have learned sooooooooooooo much!

Money well spent.

Graham W. Wolf at 46 South, Dunedin, NZ.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

September 15, 2017 at 11:49 pm

MY WIFE AND I VISITED JPL DURING AN OPEN HOUSE. THEY WERE HAVING PEOPLE ENTER THEIR NAMES TO BE ENTERED ON A MICRO DOT TO ACCOMPANY CASSINI ON ITS MISSION. WE ENTERED THREE NAMES. RICHARD GLYNN MCLAUGHLIN, PATRICIA ANN MCLAUGHLIN, AND RICHARD RUSKIN MCLAUGHLIN (OUR SON) . PATRICIA DIED IN 2002. I ALWAYS THOUGHT THAT SHE WAS TRAVELING THROUGH THE VOID WITH CASSINI. NOW THE VOYAGE FOR BOTH OF THEM HAS ENDED. HOW FITTING. THANKS TO ALL INVOLVE IN MISSION CASSINI..................SKYKING

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.