What was it like to have a front-row seat to one of the most spectacular events in the history of astronomy?

H. Hammel / MIT / /NASA

It is hard to imagine that two decades have passed since the first tiny fragment of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collided with Jupiter. When that distant Saturday dawned, neither I nor Gene and Carolyn Shoemaker had any idea what the day would bring. As I said some time later, "Comets are like cats. They both have tails, and they both do precisely what they want."

Exactly 20 years ago, on July 16, 1994, Gene and Carolyn Shoemaker and I were leading a press conference at the Space Telescope Science Institute, located on the campus of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. We were awaiting views of Jupiter taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and trying to provide some background to the press about the comet's discovery.

Suddenly, Hubble team leader Heidi Hammel walked quickly onto the stage. Gene was answering a reporter's question and suddenly stopped, looked at Heidi, and gave her the microphone. "Gene Shoemaker," she began, "said that he would be surprised if we saw nothing using HST. Well, Gene isn't going to be surprised. We saw some amazing things."

With those words, the most exciting week in our lives was underway.

It was the pinnacle of an extraordinary journey that had begun 16 months earlier, on March 23, 1993, when we were sitting at the 18-inch Schmidt telescope dome atop Palomar Mountain in California. The Schmidt camera was the first telescope put there — Fritz Zwicky began his supernova patrol with it in 1936. Gene Shoemaker began using it in the early 1980s for his Palomar asteroid and comet survey; Eleanor Helin was part of the survey during its earliest years, and later Carolyn Shoemaker joined the team.

We'd begun our observing week rather inauspiciously. Apparently someone had opened our box of films while we were gone and exposed them to light. Our first exposures were completely black. Gene thought all the film sheets were ruined, but he determined later that the ones closer to the bottom of the stack were partially usable, not at their blackened edges but close to their centers. While fresh films were being prepared, we used the bad films that first night. By about 3 a.m., the new films were ready, and we used them until we stopped at dawn.

The next evening, March 23rd, was going well until cirrus clouds began to cross the Palomar sky and we were forced to stop. We all went outside to study the cloud, and I noticed some breaks. I suggested that we continue. Gene used a financial argument against my proposal; he said that we spend some $8,000 per year on film, and therefore could not afford to waste film on a night like that one. I asked Gene if we had any of last night's bad films left. He replied that we had about a third of a box still unused. Trumping his argument about the cost, I suggested we use them since they were already officially wasted and wouldn't cost us anything. Gene looked at Carolyn, Carolyn looked me, and I looked at Gene as he said, "Let's do it!"

The very next picture was the first of the two exposures that would reveal Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 to us.

NASA / ESA / H. Weaver & E. Smith

Two months later, I received a message from Brian Marsden, then director of the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. He wrote that some interesting news would be announced within the next few days. On May 22, 1993, IAU Circular 5800 announced that there was a strong chance that all the fragments of our comet would collide with Jupiter beginning July 16, 1994. I will never forget Gene's reaction. "We're going to witness an impact," he said. "In all my life, I've wanted to see something like this more than anything else."

A few weeks after this revelation, I was enjoying dinner with planetary scientist Clark Chapman. He explained how rare and wonderful the coming event would be. Unique in the history of science, this collision of a comet against a major planet was something to be observed with every available telescope on, or near, Earth.

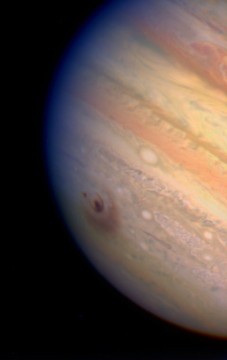

Returning to Saturday, July 16, 1994, the shoemakers and I were preparing for an evening news conference when Hal Weaver, one of the S-L 9 science team members, rushed in and presented Gene with a hastily printed message. "They saw plumes!" Gene blurted. We rushed to the nearest bank of computers so we could see for ourselves. Later, Heidi Hammel again interrupted our press conference, this time to show the first Hubble Space Telescope image. It clearly showed a large black spot high in Jupiter's cloudy atmosphere. "And this is the first, not the biggest," Hammel noted. "We're in for an exciting week."

Twenty years have passed, and yet the study of this "comet crash" still remains active. The Galileo spacecraft detected that Jupiter's ring displayed ripples in it in 1996 and in 2000, indicating that the entire ring was tilted by about 2 km following the comet's impact. Then in 2007, during its flyby of Jupiter, the Pluto-bound New Horizons probe detected continuing disturbances in the Jovian ring that apparently were still affecting the structure.

More than anything else, this comet taught us about the role that impacts have played in the history of the solar system. Comets have been shown to contain the building blocks of life, particularly "CHON" particles — consisting of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen — that form the alphabet of life.

The comet no longer exists. Nor, sadly, does Gene Shoemaker, who was killed in a car accident in Australia in 1997. But life continues here on Earth. Carolyn is retired now, and I still look for comets. I found one on my own in 2006 and shared in discovering another (Comet Jarnac) in 2010.

Those of us who witnessed the spectacle still recall that wonderful week in 1994 with awe and wonderment. Those not here yet can still imagine that moment of history — when a comet, racing along at 140,000 miles per hour, slammed into the solar system's largest planet.

Perhaps during our lifetimes, we'll witness other impacts on other planets. But Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9's spectacular demise will be hard to beat.

Learn about the inspiring life of Leslie C. Peltier, one of the greatest observers and comet-hunters of all time, in his autobiography Starlight Nights, which features an introduction by David Levy.

3

3

Comments

July 16, 2014 at 6:33 pm

We will just have to excuse you one more time Dr. Levy, as you take a drink from a glass of water, brought to Earth by a long ago comet impact, to commemorate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jim Kremsreiter

July 18, 2014 at 6:46 pm

At the time all I had was a Tasco 4.5" with it's terrible eyepieces. But I saw the most amazing sight when I saw, caused by a fragment, a huge black eye centered on the meridian. I stared at that until the planet disappeared behind the trees. Awesome! Never to be forgotten. Hard to believe that was 20 years ago.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John

July 21, 2014 at 7:08 am

I remember racing back and forth between NASA TV in the house and the 8 inch setup on the back porch pointed at Jupiter. Watching as the Hubble images were displayed and then going out to the scope to compare what I could see with my own eyes. Incredible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.