NASA’s Curiosity rover has detected both methane in Mars’s atmosphere and carbon-bearing organic compounds in its rocks.

On December 16th, team members with NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory reported that the Curiosity rover has confirmed the presence of methane and other organic compounds on Mars. But it’s unclear where these molecules come from — or whether there’s any biological connection.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SAM-GSFC / Univ. of Michigan

Organics are molecules made up of carbon atoms linked to other elements, especially combinations of hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. But they don’t automatically signal “life.” Dozens of different organic molecules occur abiotically in interstellar clouds, and they can rain down from space as micrometeoritic dust. Either way, organics would break down fast in the hostile Martian environment, destroyed by solar ultraviolet rays or by the strongly oxidizing soil, so missions have had trouble detecting them.

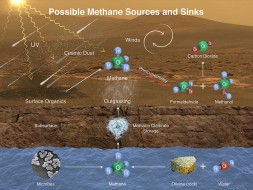

One simple organic molecule, methane gas (CH4), has a similar story. It can arise abiotically as a product of the breakdown of meteorite-borne organic matter, or from the interaction of water with silicate minerals such as olivine and pyroxene (both present on Mars). On the other hand, it can also come from primitive microbes called methanogens, which produce methane as part of their metabolic processes. (The sub-meter-scale resolution of the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s HiRISE camera has ruled out Martian cows.)

To find signs of past or present life on Mars, scientists would look for both atmospheric methane and organic-bearing rocks. And they’ve found both. “We now have full confidence that there is methane occasionally present in the atmosphere of Mars, and that there are organics preserved in ancient rocks on Mars in certain places,” announced project scientist John Grotzinger (Caltech) in a press conference at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

But the team stresses that they have no idea where these compounds come from. In fact, Grotzinger pointedly noted that neither the discovery of methane nor of organic matter argues that life is or once was present on Mars.

Drilling Martian Rocks

NASA / JPL-Caltech

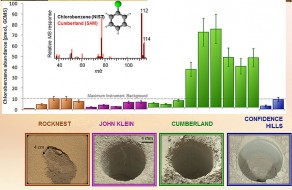

The organics detection comes from a sample that Curiosity drilled out of a rock called Cumberland on May 19, 2013 (a.k.a. sol 279 of the mission). Notably, Cumberland lies only 2 meters from another sampled rock, John Klein, which that exhibited little to no organics signature, Grotzinger said.

The team picked Cumberland because it’s full of concretions, hard spheres that form as a water-borne sediment is first solidifying into rock. Because they form so early in this process, concretions are good at encapsulating and protecting fragile organic compounds from destruction by radiation or chemical reactions (such as with the oxidizer perchlorate, detected by NASA’s Phoenix lander in 2008.)

Since drilling into Cumberland last year, Curiosity has been munching on the sample with its Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) experiment, while teams on Earth checked and rechecked its detections and ran parallel tests with clone equipment to weed out potential false alarms. Mission scientists also waited until the rover took a bite out of Confidence Hills at the base of Aeolis Mons this past September. That assay turned up no organic detection — the positive finding was unique to Cumberland.

The compound SAM identified is chlorobenzene (C6H5Cl), which has shown up before but never at the high level seen in the Cumberland mudstone (at least four times the upper levels inferred from previous samples). It’s one of four compounds that are indigenous to Cumberland, said team member Roger Summons (MIT), but it’s unclear whether it’s actually present in the rock as chlorobenzene or as something else, such as benzilic acid (C14H12O3), that’s transformed by SAM’s processing. Summons said he suspects the chlorobenzene indicates the presence of more complex organic carbon.

More Than a Whiff of Methane

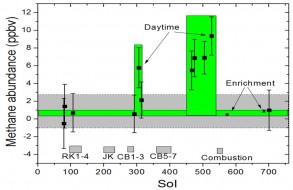

Methane has been a point of contention in Mars research for a few decades. Ground- and space-based observations have found hints of methane in the Red Planet’s atmosphere, either as global averages or plumes from discrete sources. But doubts about the interpretation of some of these results have made scientists circumspect. Adding to the debate was Curiosity’s iffy detection last year, which placed an upper limit of 1.3 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) in the atmosphere — so little that some wondered whether it was even there.

NASA / JPL-Caltech

But in fact methane is there, the team now says. The find came in late November 2013, right around Thanksgiving. “We were completely surprised, we suddenly saw 5½ ppbv methane,” said Chris Webster (JPL). “It was an Oh My Gosh moment.”

Unlike a brief whiff of methane the rover had caught previously, this one persisted. A week later the level had risen to 7 ppbv; a month later it was still at that level. A fourth test 3 weeks after that detected 9 ppbv. Then 6 weeks later, it had completely disappeared.

The average over the 2-month period is 7.2 + 2.1 ppbv, about 10 times the average atmospheric level, the team reported at AGU and online December 16th in Science.

The signal’s sudden appearance and disappearance, coupled with the low background levels, suggest that the methane came from a small, localized source either within Gale crater (where Curiosity is) or just outside it. Given the wind patterns at the time, it came from the north, said team member Sushil Atreya (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor).

“What this is telling us is that Mars is currently active, that the surface or the subsurface is communicating with the atmosphere,” Atreya said.

Methane created by ultraviolet rays breaking up organic-bearing interplanetary dust on the Martian surface is sufficient to explain the low background levels. But you need something else to explain the spike, Atreya said.

That argues for either a modern source or leakage of ancient methane from a subsurface reservoir. Once created, methane can be stored for billions of years underground, locked in molecular cages of water ice called clathrates. When something destabilizes these molecular cages — say thermal or molecular stresses, or even small impacts — the methane can escape and worm its way through fissures in the rock to the surface, where it enters the atmosphere. Within a few months winds will spread it around the planet.

Curiosity will continuously monitor methane levels to see if it can catch another spurt and follow how it dissipates, Grotzinger said. NASA has also begun coordinating with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), whose Mars Orbiter Mission is currently orbiting the Red Planet and has the ability to detect methane.

Biotic or Abiotic?

Curiosity really doesn’t have the ability to distinguish between biological and geological sources. It might get lucky if there’s some obvious biochemical structure in a large sample of organics, or if a spurt of methane is strong enough (tens of ppbv) to establish the ratios of carbon’s three isotopes and see if organic processes have enriched one over the other. But Webster warns that such carbon tests are ambiguous and difficult to do, even on Earth.

The team’s focus instead is setting the groundwork for future missions by sampling as many rock types as possible and learning to identify where organics do and do not appear, Grotzinger said. The rocks at Cumberland and John Klein formed in relatively fresh water. On the other hand, the rock sample at Confidence Hills is more complex than what they’ve seen before, containing magnetite, hematite, and maybe sulfates in addition to the clay minerals seen elsewhere. This mixture might be bad for preserving organics. The team plans to do a lot more drilling than what they’ve done in the past, in order to better understand the distribution of minerals and chemicals in the rocks.

Reference: Christopher R. Webster et al. “Mars methane detection and variability at Gale crater.” Science. December 16, 2014.

Learn more about methane and mysteries of Mars in Sky & Telescope's special issue Mars: Mysteries and Marvels of the Red Planet.

8

8

Comments

December 18, 2014 at 7:03 pm

This detection of organic compounds in Martian surface deposits is welcoming news (especially after 38 years of mixed results). Combined with the announcement of Curiosity's detection of methane in the atmosphere (after an initial failure to do so), there is at least a tiny glimmer of hope for those that support the idea that Mars has extant lifeforms hidden in some habitable niche somewhere on the planet. But as the last several decades have taught us, the detection of life on other worlds is proving to be more difficult than had been originally assumed.

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2014/05/25/the-new-search-for-life-on-mars/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kevin

December 20, 2014 at 2:06 pm

For the most part oxidation occurs on the surface of a material so it should come as no surprise that the underlying material on Mars wouldn't be red. Having said that, I was still surprised by the gray material underneath the surface because it contrasts so sharply with its "rusty" surroundings.

When you look at everything we've learned about Mars it's almost a given that there are fossils of microorganisms that once flourished on Mars in that gray material. As an Earth-bound rockhound I'm familiar with the sparsity of fossils here so if we sent up a rover to look for such fossils on Mars, there would be just a tiny chance that the rover would end up in a place that had any fossils. Wouldn't it be incredible if the first manned mission actually dug up some Martian fossils?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ROBERT STENTON

December 20, 2014 at 9:41 pm

Not just cows but humans also produce methane and not just any methane but organic methane. So if the new Mars' mantra is "Follow the Methane", perhaps it would be wiser to hold back on human exploration until this issue can be fully sniffed out.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 21, 2014 at 10:19 am

It isn't cows or humans that are producing methane, per se, it is the bacteria in our guts that produce it. And except for a subtle isotopic fingerprint (which will likely differ as a result of the details of the biochemical processes involved), "organic" methane is indistinguishable from "inorganic" methane. As for the effects of human exploration on Mars, as soon as we step foot on Mars we will do a lot more than just generate methane "pollution". We will irrevocably contaminate the Martian biosphere (assuming one exists) with the microorganisms our activity will inevitably release. This fact has been realized by scientists for a half a century now which is why some of the earliest NASA studies of Mars landers in the 1960s included provisions to preserve pristine samples of Martian soil and rock for eventual recovery by visiting astronauts so that biologically uncontaminated samples could be studied by scientists back home.

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2014/08/07/the-automated-biological-laboratory/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ROBERT STENTON

December 25, 2014 at 10:13 pm

Dear Drew,

Thanks for replying. As a human, I am actually made up of more microorganism cells than I am of mammal cells. The point is that if we are for certain to know where the methane is coming from and whether it is organic or mineral and we need to find that out before we send polluting humans. There is much talk is about the need to send humans to Mars because they can do so much more than robots. I think that it should be pointed out that there are things robots can do better than humans. If the methane is organic, the most important thing we can do on Mars if find the source of that methane. Therefore, in a very real way, robotic exploration could be a better answer than human exploration. And not just because of methane, how will we know for sure that any bugs we find on Mars are not our own. Those first few uncontaminated rocks are not likely to be the source of the methane.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

December 27, 2014 at 1:09 pm

How will we know for sure that any bugs we find on Mars are not our own?

Unless God created life on Earth and Mars using the exact same amino-acid code and DNA-sequence, identifying alien microbes with today's DNA sequencing technology would be a trivial exercise. And even if God did it, duplicating the recipe in both places, the theory-of-evolution dictates that in isolation, Martian life would have gone its own way, and be easily distinguished from our own.

Fear of contaminating another planet with Earthly biology is incompatible with the theory-of-evolution, and should only be taken seriously by Creationists.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 28, 2014 at 5:19 pm

I apologize, Peter, but the logic behind your claims escape me. Concerns about the possibility of contaminating any potential Martian biosphere (assuming one exists today) and possibly contaminating it or even irrevocably harming it has nothing to do with Creationists beliefs. It is an ethical question that scientists have publicly considered since the International Astronautical Federation VIIth Congress in Rome in 1956 as well as why we have treaties and protocols dealing with biological contamination of other worlds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

December 29, 2014 at 1:20 pm

Sorry. Should have said, "Fear of misidentifying Earthly bugs as extent Martian bugs is incompatible with..." Was only addressing the issue of identification, not contamination.

I hope the first humans on Mars are aware that dying there would violate international treaties and protocols...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.