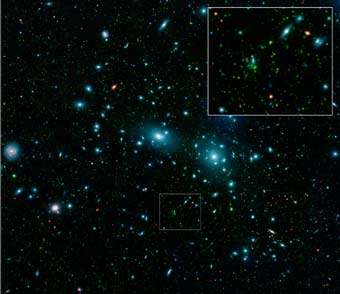

The newly discovered dwarf galaxies appear as faint green smudges in this false-color mosaic that combines visible-light data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (blue) with long- and short-wavelength infrared views (red and green, respectively) acquired by the Spitzer Space Telescope. Two large elliptical galaxies — NGC 4889 and 4874 — dominate the center of the cluster.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/L. Jenkins (GSFC)

With the far-seeing infrared eye of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, scientists peered deep into the Coma Cluster in constellation Coma Berenices and dramatically increased the number of known dwarf galaxies within the cluster. With the observations, scientists can better understand galaxy evolutions.

Leigh Jenkins and Ann Hornschemeier (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center) presented the evidence on Monday at the American Astronomical Society conference in Honolulu. Dwarf galaxies may be the first galaxies to form, and they reveal hints of how the universe is structured. To search for them, the astrophysicists used Spitzer to acquire 288 images of the cluster's core and an outlying region.

While many of the 30,000 objects they found were background galaxies, Jenkins estimates that at least 1,200 of these objects are dwarfs in the Coma Cluster, nearly 320 million light-years away. Since Spitzer looked at only a portion of the cluster, the results imply a dwarf-galaxy population of at least 4,000, says Jenkins.

"But there are probably more dwarf galaxies, perhaps by a factor of two or three, lurking in our data," added Hornschemeier.

Unlike the Milky Way, which has around 300 billion stars, dwarf galaxies contain only a few billion. The dwarf galaxies' masses are comparable to, or slightly less than, the mass of the Small Magellanic Cloud (30 billion stars), the second closest galaxy to the Milky Way.

Spitzer is the main reason scientists have found all of these dwarfs; the telescope took each of the nearly 300 separate images in a mere 70 to 90 seconds. "If you surveyed this similar-sized area as deep in [the visual band], you'd expect to find at least some of these dwarfs, but it's very hard to go that deep in anything close to the amount of time we were able to invest in this field," explained Hornschemeier. "So it's really a question of the sensitivity and efficiency of the data."

Hornschemeier and others are making follow-up spectroscopic measurements with telescopes at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and MMT Observatory in Arizona to figure out if additional dwarf galaxies are in the Coma Cluster. These additional studies may address secondary questions as well. "Have these dwarfs fallen in recently or have they been with the cluster a very long time?" Hornschemeier says. "That's one question we'll be able to answer as the data comes in."

Their results will be in an upcoming edition of Astrophysical Journal.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.