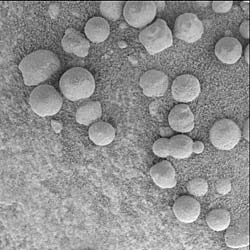

By analyzing several 'blueberries' in a group with its spectrometers, Opportunity could determine their composition.

Courtesy NASA / JPL.

When planetary scientists reviewed potential landing sites for the Mars Exploration Rovers, Meridiani Planum rose to the top of the list. Opportunity's future destination was known from orbital studies to be covered by hematite — a mineral often associated with water on Earth. Now, scientists have not only verified that Meridiani is covered by hematite, they are closer to determining how it got there.

When Opportunity arrived, opened its eyes, and looked around with its thermal spectrometer, "Bang! We saw hematite right away," said MER principal investigator Steven Squyres (Cornell University) yesterday at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston, Texas. The surface appeared covered with the stuff, but there was very little inside the small crater where Opportunity came to a rest. Moreover, Squyres notes, the bounce marks left behind by Opportunity's air bags show no hematite.

Close inspection of the rover's surroundings found the region filled with countless BB-sized pebbles affectionately dubbed "blueberries" by MER team members. "These granules are astonishingly spherical," says Squyres. Various studies determined that they are concretions — minerals formed by groundwater percolating through rocks. The fact that these pebbles exist in the first place is among the leading pieces of evidence that Meridiani Planum was once soaked with water.

Several blueberries have collected inside a small depression called the berry bowl (arrowed).

Courtesy NASA / JPL.

But until now, it wasn't clear what the blueberries were made of. To find out, engineers drove Opportunity to a spot called the berry bowl, a depression in the crater's exposed rock outcrop where several blueberries have accumulated. The BBs are too small to analyze individually, so they need to be looked at in a group.

The answer: "These are hematite concretions," says Squyres. "They have hematite. Tons of it!" The team reached this conclusion after Opportunity analyzed the berry bowl with its Mossbauer Spectrometer.

In light of all the other evidence, it seems clear that Meridiani Planum was an area that had ample ground water: enough to form and excrete hematite from the rocks. Opportunity was sent to Meridiani to look for this mineral.

Not only has the rover found it, scientists know how it formed and what state it is in.

So what's next? With the source of the hematite solved, Opportunity will soon exit its home crater and start rolling across the flat landscape toward Endurance Crater, 740 meters to the east. Inside Endurance, which is much larger and deeper than the rover's home crater, MER team members hope to find additional outcrops to help them better constrain the geologic history of Meridiani Planum.

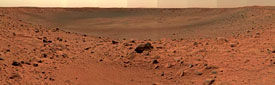

This stunning look inside Bonneville Crater by Spirit's Panoramic Camera shows a disappointing dearth of geologically interesting features. Engineers are unlikely to direct the rover into the depression.

Courtesy NASA / JPL / Cornell University.

Meanwhile, on the other side of Mars, Spirit is in the process of scoping out Bonneville Crater. Unfortunately, initial inspections have been disappointing. According to science team member Ray Arvidson (Washington University in St. Louis), the rover's peek inside Bonneville has thus far failed to find any outcrops or other features that would entice the team to have Spirit venture inside.

"We will do a circuit of the rim and look at the dark soil inside," says Arvidson. But it seems likely that Spirit will soon move on toward a hill complex to the east.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.