With so many beautiful pictures of spiral galaxies available, it might seem strange to highlight yet another image. But NASA's recent press release highlighting NGC 2841 merits the fuss.

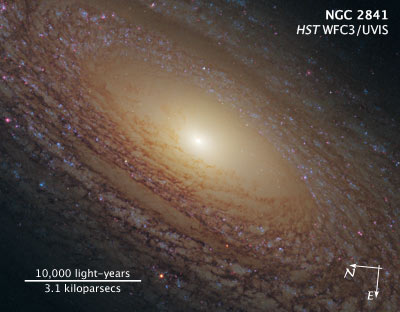

This Hubble Space Telescope image captures the spiral galaxy NGC 2841 in remarkable detail. Click above for a larger image.

NASA / ESA / STScI / AURA

NGC 2841 is a 9th-magnitude galaxy 46 million light-years away in the front leg of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. In many ways it's a classic example of a spiral galaxy: plenty of dust, inner populations of yellowish, middle-aged stars toward the center while bluer and younger stars congregate along the outer spiral arms.

However, NGC 2841 defies the norm when it comes to star-formation rate — compared to other galaxies of its kind, it lacks the emission nebulae that indicate star formation, boasting instead a larger-than-average population of young, blue stars. Stellar wind from the super-hot young stars may have blown off the gas that would allow further star formation in their vicinity.

Exposures for the new image were taken in 2010 with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 totaling two hours through four filters ranging from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths. The dust arms are captured in extraordinary detail.

3

3

Comments

Peter Wilson

February 22, 2011 at 7:19 am

"NGC 2841...lacks the emission nebulae that indicate star formation..." I must be looking at the wrong photo, because I see pink emission nebulae all over!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Adolf Schaller

February 27, 2011 at 1:15 pm

A "larger-than-average population of young blue stars" obviously demonstrates that plenty of gas for continued star formation must be present. As Peter Wilson notes, there is an abundance of emission nebulae to be seen throughout this system. However, the emission nebulae all seem to be relatively small and fairly uniform in size, with the largest examples apparently occupying the peripheral regions of the galaxy. Some mechanism appears to have prevented large star-forming complexes from condensing. One possibility is that the gas reservoir may be confined to a relatively undisturbed 'thin disk' distribution. Something in the galaxy's history (probably its last big merger event) might have originally fostered such a thin-disk morphology, and the galaxy probably hasn't consumed many dwarf galaxies to disturb its relative tranquility since. The corollary is that spawning very large 'starburst' complexes may require more than just gravitational condensation assisted by cooling dust: disturbances from infalling gas-rich dwarf systems may trigger a spate of star formation by propagating shockwaves through the disk gas which can produce atypically massive star-forming regions. Subsequently, a confluence of colliding large cluster winds and supernova shockwaves that ensue can sustain the process of producing more large star-forming complexes until the gas in an extended region has either been consumed or blown away. The common twin-armed galactic spiral arm structure type seems to be consistent with this mechanism, but such a robust spiral pattern seems to be conspicuously muted in NGC 2841, most likely because the small and evenly distributed star-forming regions and their relatively small clusters probably have enough to clear out or trigger other small star forming complexes within only a restricted localized region.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

February 28, 2011 at 8:20 pm

I suspect we have some story telling about NGC 2841 and the blue stars. How can you discern the difference between 1st generation blues stars in NGC 2841 vs. descendants from many past generations? You really cannot without engaging in various assumptions about the unobserved past of NGC 2841.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.