New results from NASA's Dawn orbiter show that the largest asteroid (and acknowledged dwarf planet) must possess a global layer of water ice that lies just below its dark, dusty surface.

Even before NASA's Dawn spacecraft reached asteroid 1 Ceres in March 2015, planetary scientists knew that this sizable world was not the dry-as-dust object that comes to mind when we imagine what asteroids should be like. For starters, it has a density (2.1 g/cm3) far too low for a solid ball of silicate rock. Infrared spectra taken as long ago as 1978 revealed the presence of water-infused clay minerals on its surface, and scans by ESA's Herschel space observatory a few years ago even caught Ceres exhaling clouds of water vapor.

NASA / JPL / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA / PSI

But one surprise from Dawn is that, apart from a smattering of bright spots here and there inside craters, there's not a lot of ice actually exposed on the surface. Whatever ice Ceres has must lie deeper down.

Now, it turns out, "deeper down" is probably no more than 1 or 2 meters, and that water ice must be everywhere. As detailed in this week's Science, the broken-up rubble on Ceres' surface contains high concentrations of hydrogen — and, cosmochemically speaking, water ice is the only likely compound to account for all that hydrogen. In fact, as Thomas Prettyman (Planetary Science Institute) and his colleagues explain, the near-surface rocks contain up to 10% water by mass, and this global ice layer likely extends to great depth.

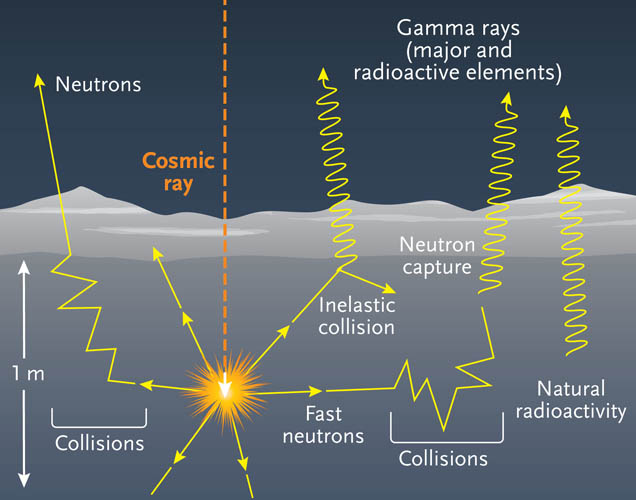

S&T diagram; source: T. Prettyman & others

Dawn's Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRAND) slowly built up maps of neutrons and gamma rays escaping from Ceres as the spacecraft orbited. "Gamma rays provide a fingerprint of what's in the surface," Prettyman explains, because they're the end product of complicated interactions of neutrons triggered by cosmic rays. Importantly, GRAND only detects neutrons and gamma rays extremely close to the surface, within about 1 meter.

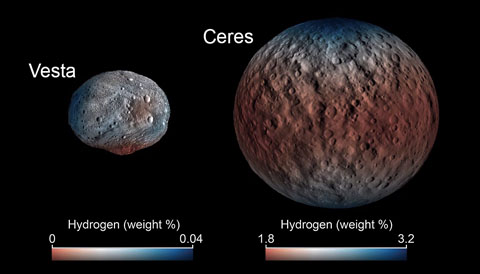

The resulting maps show that the near-surface hydrogen is roughly 100 times more abundant than was found on 4 Vesta, Dawn's previous host, which is largely covered with basaltic rock. On Ceres, the hydrogen signature is very uniform and increases dramatically toward the poles. The team interprets this gradation as a shift from minerals that reacted with (and incorporated) liquid water near the equator to near-surface water ice beginning at latitudes poleward of about 40°. There, Prettyman explains, water ice is probably filling the gaps between fine particles of dust.

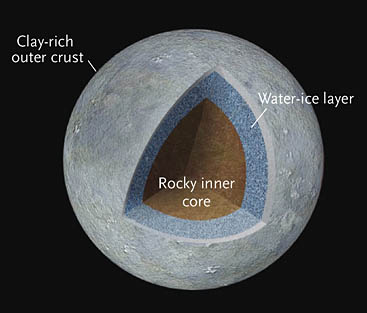

This water didn't come from impacting comets but rather must have been present when Ceres formed. Early in solar-system history, this body likely was at least warm, if not hot, due to the kinetic energy of near-constant bombardment and the decay of radioactive elements in its rocky matter, so the interior of Ceres separated into a rocky core surrounded by a less-dense exterior.

NASA / JPL

It's not clear how far this differentiation progressed. But it's no great leap to imagine that Ceres once had a global ocean (or at least an outer layer of briny mud). Over time, sunlight warmed the equatorial regions enough to drive out the near-surface water and concentrate it at the poles.

Yet exposures of water ice aren't common on the surface. Sure, there are some really bright spots in the big crater Occator, but those are likely salt deposits. (Last month the IAU's Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature quietly announced that the bright spots inside Occator now have names. The main spot is Cerealia Fcaula, and the slightly less obvious ones to its east are collectively Vinalia Faculae.)

Dawn's spectra suggest that water exists on the floor of a crater called Oxo and within some (but not all) of hundreds of polar craters that are persistently shadowed. These "cold traps," explains Norbert Schörghofer (University of Hawaii), accumulate water vapor over time that's been driven from Sun-warmed surfaces elsewhere.

So why isn't Ceres icy white all over instead of the very dark surface (only 9% reflective) seen today? Here's my guess: Ceres likely came together with a large helping of the kind of carbon-rich rock found in primitive, carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. Every time something blasts into Ceres, it creates a plume of ejected debris that spreads outward and over the surface. It's a mix of carbon-infused dust and water. Some of the water plops back onto the surface and eventually migrates toward the poles. But water vapor is vulnerable — ultraviolet sunlight readily breaks it down into hydrogen and oxygen — and so over time what settles back onto the surface becomes ever more desiccated.

That's just my hunch, of course. What the new Dawn results do confirm is the longstanding prediction that ice can survive for billions of years just beneath the surface of a body like Ceres. And now there's a much stronger case, Prettyman notes in a NASA press release, that near-surface water ice exists on other main belt asteroids.

To learn more, check out yesterday's press briefing at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, where Prettyman, Schörghofer, and others presented their results. And Marc Rayman, Dawn's mission director, details all of the results from Ceres in Sky & Telescope's December issue.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.