After a 5-year-long journey, NASA's Juno probe, an emissary to the largest planet in the solar system, has arrived at its destination and slipped into orbit around Jupiter.

NASA / JPL

"Joy" at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's mission control center today is spelled JOI — for Jupiter Orbital Insertion.

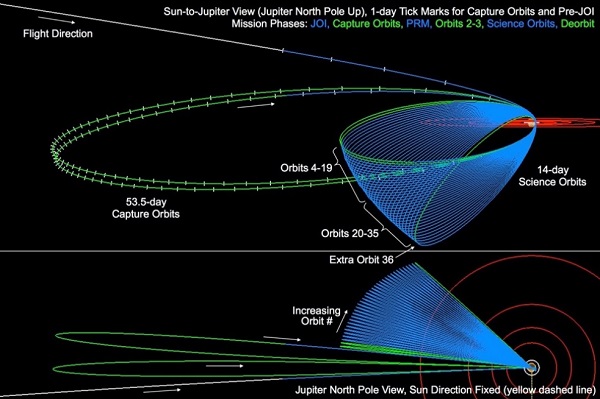

July 4th fireworks erupted in the outer solar system overnight, as the Juno probe fired its main engine and entered a polar orbit around Jupiter at 11:53 p.m. EDT (Earth receive time), which was 3:53 Universal Time (UT) on July 5th. Juno carried out a scheduled 35-minute-long burn that slowed its velocity by 542 meters per second (1,212 mph), enough to become a captured satellite of Jupiter with an initial 53.5-day orbital period. Arriving at 58 km per second with respect to the planet, Juno also performed the fastest orbital insertion to date.

"Independence Day always is something to celebrate, but today we can add to America's birthday another reason to cheer — Juno is at Jupiter," notes NASA administrator Charlie Bolden in a post-arrival press release. "With Juno, we will investigate the unknowns of Jupiter's massive radiation belts to delve deep into not only the planet's interior, but into how Jupiter was born and how our entire solar system evolved."

Unfortunately, Juno won't return any eye-candy images during its arrival, as all science instruments were turned off during the crucial engine burn. Juno resumed full transmissions to Earth 58 minutes after the the thruster lit up, indicating all is well with the spacecraft. At 5.8 astronomical units (a.u.) or 869 million km from Earth, Juno is currently more than 48 light-minutes away, with a corresponding lag time as transmissions reach NASA's worldwide Deep Space Network.

Launched on August 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral atop an Atlas V rocket, Juno took almost five years and one Earth gravitational assist flyby (on October 9, 2013) to reach Jupiter.

Juno is the second in the series of three New Frontiers program missions for NASA: the first was the New Horizons mission to Pluto and beyond (launched in 2006), and the next is the Origins Spectral Interpretation Resource Identification Security REgolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) asteroid sample-return mission, now being readied for launch in September.

Juno's looping initial orbit keeps it well clear of the most intense charged-particle belt trapped around the planet. It also means that the spacecraft won't return to the planet's immediate vicinity until August 27th. On October 19th, Juno will fire its main engine one final time to drop the spacecraft into a series of tighter, 14-day-long science orbits. Juno also revved its rotation up from two to five revolutions per minute during today's orbital insertion maneuver. Spinning the spacecraft allows for stabilization without the use of reaction wheels. The very first spacecraft to explore Jupiter — Pioneers 10 and 11 in the early 1970s — utilized the same approach.

The Juno Probe's Dangerous Assignment

The mission's three major objectives are to study Jupiter's polar magnetosphere, assess the composition of its atmosphere, and probe its deep interior. To accomplish this, the spacecraft must duck under the planet's intense radiation belt and thread a target zone just above its cloudtops.

NASA / JPL / SwRI / MSSS

Juno will plunge closer to the Jovian cloud tops than any mission before, passing just 4,200 km (2,600 miles) away over the course of 36 orbits. Its instruments will also examine Jupiter's polar regions close up on each successive close pass, another first.

NASA / JPL

Does Jupiter possess a solid rocky core at its heart, or are those heavy elements dissolved in a sea of metallic hydrogen all the way though? How similar is the source Jupiter's powerful magnetic dynamo to the Sun's? Juno will, for the very first time, sound the interior of our solar system's largest planet in a effort to tell the story of its current state and, perhaps, its origin and role in the formation of the solar system.

"Where is the water?" is a major question that mission scientists expect Juno to answer. NASA's Galileo probe plunged into Jupiter's atmosphere on December 7, 1995, and measured a curious lack of water during its brief 48 kilometer per second plunge. Is this paucity of H2O the norm for Jupiter's upper atmosphere, or did the probe merely hit a dry patch? Either answer has enormous implications for models of planetary formation.

The Juno probe will also test frame-dragging, as predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity, as it maps the gravitational field of Jupiter.

Sounding the Jovian Depths

Like its namesake, the queen of the gods in Roman mythology, Juno will see through the cloudy veil of Jupiter to probe its true self. Juno even carries three Lego depictions of the deities Jupiter, Juno, and the 17th-century astronomer Galileo, as well as a portrait of Galileo and a brief observation of Jupiter by the famous scientist.

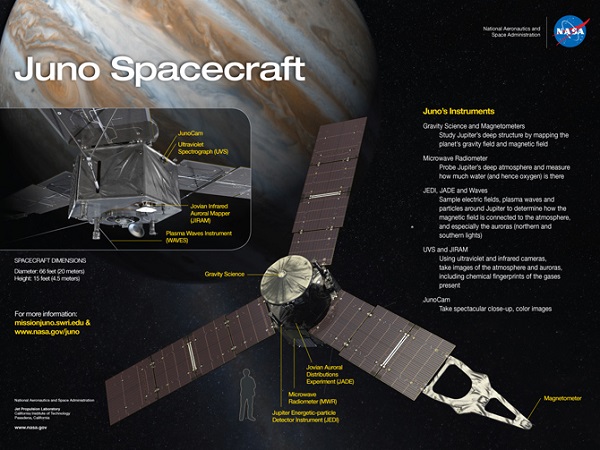

To carry out its mission, Juno carries a suite of instruments:

JunoCam: The craft's sole camera will provide closeup images of the polar regions of Jupiter during each flyby. As part of an online outreach campaign, members of the public will help choose image targets for JunoCam, coordinated with an amateur observer campaign. Taking images from a spinning spacecraft is difficult, and JunoCam overcomes this using a "push broom" imaging technique, taking consecutive thin strips of images during each spin and later building them up into a single comprehensive image.

Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVS) and Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM): These imagers will study the compositions of clouds and hazes in Jupiter's uppermost atmosphere at ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths, respectively.

ESO / L. Fletcher

Radio and Plasma Wave Sensor (Waves), Jovian Energetic particle Detector Instrument (JEDI), and the Jovian Auroral Distribution Experiment (JADE): These detectors will study the interrelationship between Jupiter's atmosphere and magnetic field and chronicle auroral activity on Jupiter.

Magnetometers and Gravity Science instrument (MAG and GS): Their goal is to map the planet's magnetic and gravitational field.

Microwave Radiometers (MWR): Able to penetrate deep into Jupiter's atmosphere at microwave wavelengths, MWR will map the depth and extent of atmospheric circulation. MWR will also measure the amount of water present in Jupiter's atmosphere.

Juno's instruments are contained within an enormous titanium vault, in an effort to shield them from Jupiter's extensive radiation belts. Even then, orbital precession will eventually drag the spacecraft into the deadly belts, ending the mission.

NASA / JPL

Juno is also the first spacecraft to explore the outer solar system powered not by a plutonium-fueled radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), like those used on the Voyagers , Galileo, and Cassini, but by solar energy. The three solar arrays powering Juno are enormous, spanning 20 m — roughly the size of a basketball court. At five times Earth's distance from the Sun, solar energy in the vicinity of Jupiter is 1⁄25 of what Earth receives. Juno's enormous solar panels generate about 500 watts of energy, enough to power a small kitchen refrigerator. Half of that power goes simply to heating the core of the spacecraft.

With those large solar panels, the Juno probe must carefully thread Jupiter's powerful magnetosphere, avoiding a torrent of electrical current that sometimes reaches millions of amps. One encounter with the powerful Io plasma torus linking the innermost Galilean moon with Jupiter would doom the mission.

NASA/Jack Pfaller

Radiation exposure is a very real threat to the mission. On Earth, we're exposed to about a third of a rad a year at sea level from natural background sources. Over its 1½ years of operation, Juno will be exposed to an amazing 20,000,000 rads, a lethal dose for humans many times over.

The end of mission comes on February 20, 2018, when engineers will direct Juno to burn up in Jupiter's atmosphere, avoiding any future contamination of Jupiter's large moons.

Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to flyby Jupiter in 1973. Other Jupiter flyby alumni include Pioneer 11, Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini, New Horizons, and Ulysses. To date, Galileo was the only other mission that entered orbit around Jupiter, operating from 1995 to 2003.

Observing Jupiter

You can also catch Jupiter high in the evening sky looking west just after sunset and join the amateur collaboration in an effort to monitor Jupiter leading up to Juno's crucial observation passes. Jupiter passed opposition for 2016 on March 8th, and it will slip behind the Sun and move into the morning sky this September.

A new orbital outpost in the solar system is now "open for business." Time to explore the mysteries of Jupiter!

3

3

Comments

Bob

July 6, 2016 at 1:49 pm

Interesting article. Thanks.

Bob

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don-Kerouac

July 8, 2016 at 10:39 pm

Fine write up on the Juno mission.

Why risk failure with the enormous solar panels given the proven track record of the RTG on past successful missions?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

July 12, 2016 at 2:22 am

The main issue is the lingering Plutonium shortage for deep space missions. For example, the Pu used to power Curiosity was purchased from the Russians. The good news is, the U.S. has restarted Plutonium production for NASA, but it'll take years for the production pipeline to reach the launchpad.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.