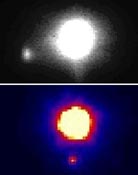

A satellite roughly 35 kilometers across has been found circling the large, main-belt asteroid 22 Kalliope by two teams of astronomers working just hundreds of yards apart on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. William J. Merline (Southwest Research Institute) and Francois Menard (Grenoble Observatory) first noticed the satellite in infrared images taken on the morning of September 2nd with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope. At the time the companion was about a half arcsecond (roughly 1,000 km) from Kalliope and 4.9 magnitudes (90 times) fainter than Kalliope itself. Follow-up observations the next day cinched the moonlet's reality.

Courtesy William J. Merline & Francois Menard.

A satellite roughly 35 kilometers across has been found circling the large, main-belt asteroid 22 Kalliope by two teams of astronomers working just hundreds of yards apart on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. William J. Merline (Southwest Research Institute) and Francois Menard (Grenoble Observatory) first noticed the satellite in infrared images taken on the morning of September 2nd with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope. At the time the companion was about a half arcsecond (roughly 1,000 km) from Kalliope and 4.9 magnitudes (90 times) fainter than Kalliope itself. Follow-up observations the next day cinched the moonlet's reality.

Meanwhile, another team had already come to the same realization. Jean-Luc Margot and Michael E. Brown (Caltech) had been following the asteroid since the morning of August 29th. Also observing in the infrared, Margot and Brown were using the adaptive-optics system on the Keck II telescope. Both teams reported their findings to the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center, which issued a joint announcement on IAU Circular 7703.

About 180 km across, Kalliope has an M-class spectrum, which has traditionally denoted bodies thought to have metallic (iron-nickel) composition. But M asteroids also mimic the spectra of silicate-dominated, metal-poor meteorites called enstatite chondrites. Although interesting in its own right, the new satellite — officially designated "S/2001 (22) 1" — will be a powerful tool for deciding between these possibilities. Determining its orbit will yield Kalliope's mass and, in turn, its bulk density. For now, Margot says, "Our data are consistent with a period of between 3 and 4 days," but he cautions that everything is guesswork at this point. Another opportunity to divine something about Kalliope will come in December, when a team led by Christopher Magri (University of Maine) attempts to detect radar echoes from from its surface using the Arecibo radio telescope.

The count of double asteroids is growing steadily, with 12 known and another five suspected. Observers have found three paired systems this year alone.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.