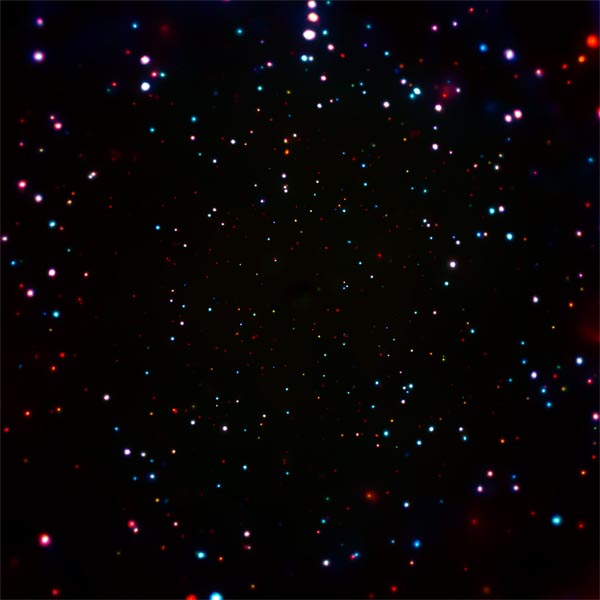

The Chandra X-ray Observatory has gazed at a small patch of sky for almost 12 weeks, revealing 1,008 X-ray-emitting sources — most of them supermassive black holes.

NASA / CXC / Penn State Univ. / B. Luo et al.

Astronomers at the winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society unveiled the "deepest" X-ray image ever made: a 7-million-second exposure of a patch of sky about two-thirds the size of the full Moon, gathered by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory during 102 pointing sessions between 1999 and 2016. Most dots in this image are supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies billions of light-years away.

Neil Brandt (Pennsylvania State University) introduced the image, and the science it produced, on January 5th as he accepted the Rossi Prize, awarded yearly for significant contributions to high-energy astronomy.

The image, known as the Chandra Deep Field South, shows 1,008 discrete sources, each of them emitting X-rays with energies between 500 and 8,000 electron volts (0.5–8 keV). It's an incredibly deep image — for the very faintest sources detected in this image, Chandra captured only one X-ray photon every 10 days!

Since Chandra tabulates individual photons as they come in, this is far more than just an image. It's also a light curve and spectrum of every source. The time-lapse animation below is made from 4 million seconds of the data. Every twinkling dot is a supermassive black hole. The still dots are largely quiescent galaxies with X-ray emitting stars. The field of view, in the southern constellation Fornax, is about 20 arcseconds across.

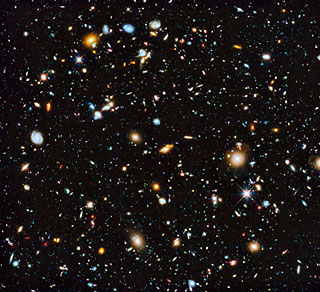

Multiple telescopes, including the Hubble, Spitzer, and Herschel space telescopes, along with the Keck telescopes and Very Large Telescope here on Earth, among others, have all observed the same field, so it's possible to map almost every X-ray source to its counterparts at other wavelengths, such as infrared, radio, or visible light. (For example, the much narrower and deeper Hubble Ultra Deep Field sits at the center of this image.) Almost every source also has a measured redshift and hence a known distance.

More Than a Pretty Picture

So what do these twinkling Christmas lights tell us? They shed light on nothing less than the birth and growth of supermassive black holes.

To understand a unique study by Fabio Vito (Pennsylvania State University and University of Bologna, Italy) and colleagues, you first have to know that while Chandra imaged more than a thousand sources emitting X-rays, there are tens of thousands of galaxies in the same field, as seen by Hubble and other telescopes at various other wavelengths. Most of these galaxies don't produce enough X-rays for Chandra to detect. Yet they probably do have some very faint X-ray emission, if not from their central black hole then from stars within the galaxy.

NASA / ESA / S. Beckwith (STScI) / HUDF Team

What Vito and colleagues did was to cut out regions of the Chandra Deep Field South around 2,000+ distant galaxies (from a universe less than 1.8 billion years old) that were not detected in X-rays. Then they stacked those cutouts, effectively combining them into a single X-ray image with the equivalent of more than 30 years' worth of exposure time depicting the average X-ray emission from a galaxy in the early universe.

"We're looking back to times when black holes were in crucial phases of growth, similar to hungry infants and adolescents," Vito says.

This average galaxy that Vito and colleagues see is rife with star formation — not black hole growth. This means that black holes aren't growing throughout their lifetimes; instead, they appear to experience long quiescent periods interspersed with short growth spurts.

We already know that black holes with a billion Suns' worth of mass existed just a billion years after the Big Bang. In theory, it's hard to build such a massive black hole that quickly. So if they're not growing continuously from the moment they're born, then they probably didn't start as stellar mass objects. More likely, the seeds for supermassive black holes must have already been quite large, 10,000 to 100,000 times the mass of the Sun. These seeds might have formed from the direct collapse of massive clouds of gas in the early universe.

The Black Hole-Galaxy Connection

Another result presented at the AAS meeting shows that we still have far to go in understanding black hole evolution. We've long known that supermassive black holes appear to grow at the same rate as the stars form in their host galaxies. But the connection between black hole and galaxy growth has remained elusive. (In fact, we devoted a feature to the topic in the February issue of Sky & Telescope.)

Now, Guang Yang (Pennsylvania State University) and colleagues show that this growth connection appears to be a secondary effect. Instead, a black hole's growth rate appears to be more strongly connected to the total stellar mass than to the number of new stars forming. In other words, more massive galaxies appear to be more efficient in feeding their central black holes — though why this should be the case is still up for debate.

This mystery is one of many that remain unanswered, at least for now, but astronomers have only begun to plumb the depths of the Chandra Deep Field South.

1

1

Comments

Richard_21

January 13, 2017 at 3:21 am

We need new astrophisics and cosmology, to explain observations like this one. At first black hole definition must bee formed...and then cosmological principle should be at least suspended.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.