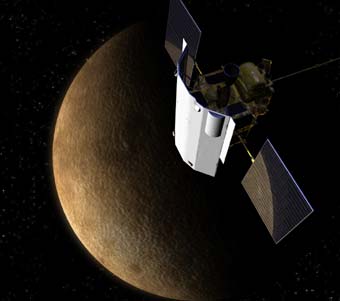

The Messenger spacecraft, seen here in an artist's concept, is equipped with two cameras, a laser altimeter, three spectrometers, and a magnetometer.

NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

NASA’s Messenger spacecraft, nearly three years into its flight to reach Mercury in January 2008, swung close to Venus on Tuesday for a necessary gravity assist. It also gave scientists a chance to test its instruments before reaching the innermost planet. During the flyby, Messenger teamed up with the European Venus Express (which has been orbiting Venus since April 2006) to carry out collaborative studies focusing on the planet’s atmosphere.

Messenger reached its closest point to Venus on Tuesday at 7:08 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, passing within 340 kilometers (210 miles) of the planet’s surface. During this time, the largely solar-powered spacecraft fell into the shadow of the planet for 20 minutes and relied on its internal battery, which reached full charge again two hours later. The flyby went smoothly and all seven instruments were functional, according to scientists.

“This is the first time we are able to take observations [of Venus] from two different vantage points with complementary sets of instruments,” said Messenger principle investigator Sean Solomon (Carnegie Institution of Washington) in a press conference. Scientists hope to observe cloud patterns, magnetic fields, and how the atmosphere interacts with the solar wind.

One goal of studying Venus is to learn more about “how climate change works on planets,” explains Venus Express scientist Hakan Svedhem (European Space Agency). With a thick, dense atmosphere of mainly carbon dioxide and sulfuric-acid clouds, Venus has the strongest greenhouse effect of the planets in the solar system, says Svedhem, and studying it may lead to models for understanding Earth's climate.

When Messenger flew by Venus the first time in October 2006, the planet was on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth, causing a radio blackout.

Since noon Eastern time today, scientists have started to download the roughly 6 gigabits of data — 630-plus images and other observations — that Messenger took within its 73-hour observation period. By Friday they hope to have color pictures of Venus, according to Messenger engineer Eric Finnegan (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory).

While past spacecraft have used planetary passes to launch themselves farther into space, Messenger’s flybys of Venus are doing the opposite — the second flyby slowed the spacecraft from 36.5 to 27.8 kilometers per second so it can settle into Mercury’s orbit. Aside from the planetary gravity assists, Messenger will execute three trajectory corrections using its main engine, and can take 13 additional maneuvers if needed. “Over the next 18 months, the spacecraft will travel on a veritable roller coaster,” says Finnegan.

Messenger is scheduled to arrive at Mercury on January 14, 2008, Earth’s first visitor to Mercury in more than three decades (the first was by Mariner 10). Messenger will take images of the never-before-seen side of the largely unstudied planet, sweeping by two more times in October 2008 and September 2009 to map most of the surface, record atmosphere composition, and gather data that will help scientists plan the yearlong orbital mission starting in March 2011.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.