Engineers have decided to keep the Jupiter probe, Juno, in its current orbit until an issue with its engine can be addressed.

| Update (October 19): Juno sure likes to keep us hopping! An anomaly caused the spacecraft to enter electronic hibernation at 1:47 a.m. EDT. The spacecraft acted as expected during the transition into this "safe mode," restarted successfully, and is healthy. High-rate data has been restored, and the spacecraft is conducting flight software diagnostics. All instruments are off, and the planned science data collection for today's close flyby of Jupiter did not occur. Scott Bolton (NASA) explained at the ongoing meeting of the Division of Planetary Sciences that the problem was with valves in propulsion system. Find more information from NASA's recent press release. Meanwhile, data from the first perijove flyby are still revealing intriguing results, showing that Jupiter's belt-zone structure extends at least 400 km deep! |

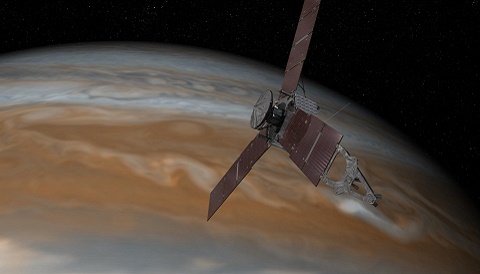

NASA / JPL-Caltech

NASA has announced that its Juno mission will stay in its current, wide-ranging orbit for at least one more pass.

The announcement came prior to a so-called period reduction maneuver (PRM) which was set to occur today. This would bring Juno closer to Jupiter, shortening its orbit from the current 53.4 days to just two weeks. An anomaly experienced by a set of valves controlling the spacecraft's fuel pressurization system triggered the decision. This PRM burn will be the last time Juno is scheduled to fire its main engines.

“Telemetry indicates that two main helium check valves that play an important role in the firing of the spacecraft's main engine did not operate as expected during a command sequence that was initiated yesterday,” says Juno project manager Rick Nybakken (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) in a recent press release. “The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes. We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine.”

The burn was one of the first major events for the mission after Jupiter emerged from behind the Sun and its glare on September 26th. The decision to postpone the burn came after NASA consulted with the Lockheed Martin Space Systems engineers who designed the spacecraft. The next opportunity for Juno to carry out this firing is during its next pass near Jupiter on December 11th.

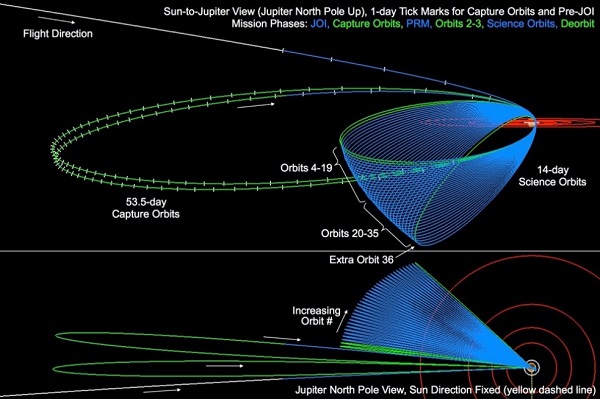

NASA / JPL-Caltech

In its present orbit, Juno ranges from an altitude above Jupiter of 4,300 km (perijove) out to 8.1 million km (apojove), more than 20 times the Earth-Moon distance and far beyond the orbit of Callisto. Following Kepler's Laws, Juno spends most of its time along this elongated orbit at its most distant point, briefly sweeping in toward the planet — and through its most intense exposure to high-energy charged particles trapped in Jupiter's magnetosphere — on each pass.

What's Next for Juno

This turn of events also means that the spacecraft's cameras and science instruments will stay on for this week's close pass of Jupiter — they were due to be shut off during the engine burn. NASA is now scrambling to make the most of this week's pass. We should see science returns similar to the first perijove pass this past August.

“It is important to note that the orbital period does not affect the quality of the science that takes place during one of Juno's close flybys of Jupiter,” said principal investigator Scott Bolton (Southwest Research Institute) in the October 14th press release. “The mission is very flexible that way. The data we collected during our first flyby on August 27th was a revelation, and I fully anticipate a similar result from Juno's October 19th flyby.”

Launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on August 5, 2011, Juno entered orbit around Jupiter on July 4th this year. Designed to probe Jupiter's interior as well as its gravity field and magnetosphere, the probe's first pass has already returned some amazing science. The most tantalizing part of keeping the spacecraft in such a wide-ranging pass is the long wait between science collection phases. Also, Juno sustains cumulative radiation exposure and subsequent damage on each pass, another reason that researchers are eager to get down to business.

This change in plans will force the amateur astronomer campaign observing Jupiter to reschedule their observations as well. A plan outlined by Candice Hansen on the Planetary Society blog to capture some far images of selected moons (an extra project, as the mission wasn't designed for satellite science) has also been put on hold for the time being.

Juno is set to end its mission in February 2018 after 37 orbits, burning up in the atmosphere of Jupiter. It's unclear at this point just how firm this end of mission date is, and if the health of the spacecraft could force the date to move up or move back.

At this point, it's also unclear just what caused the engine anomaly. NASA plans to hold a press conference today (October 19th) at 4:00 p.m. EDT / 20:00 GMT to address Juno's current status.

We'll have updates then. Remember: space is hard, and life as a solar-powered spacecraft in the outer solar system is even harder.

1

1

Comments

Robert-Black

October 21, 2016 at 4:13 pm

This part of the solar system is where plutonium powered RTG's are perfect. Why they don't use them is a mystery. I hope the anti-science greenies didn't influence this decision. Solar power out there is << at Earth, so the spacecraft dependent on that will always be energy starved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.