Why is the time of the equinox so specific? S&T's editors explain.

For those of us already seeing blushing foliage or feeling a chill in the air, it might seem as though autumn has already arrived. But astronomically speaking, fall officially comes to Earth's Northern Hemisphere at 20:44 Universal Time on Sunday, September 22, 2013. At that moment, the Sun's path crosses Earth's equator heading south, an event called the autumnal equinox.

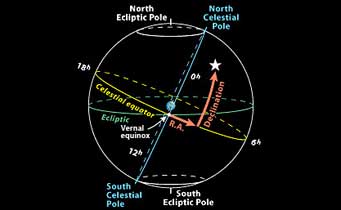

The Earth's spin axis isn't at right angles to the plane of its orbit around the Sun. One consequence: the celestial-coordinate system is tilted with respect to the ecliptic (the path followed by the Sun through the stars over the course of a year). The equinoxes occur when the Sun crosses from one hemisphere to the other.

S&T / Gregg Dinderman

Why do we say summer ends and fall begins at an exact moment, when the natural events happen gradually? Because the four seasons many of us use — winter, spring, summer, and fall — have beginning and ending points defined as actual key moments in the Earth's annual orbit around the Sun — or equivalently, from our point of view, the Sun's annual motion in Earth's sky.

The Sun appears farther north or south in our sky, depending on the time of year, because of what some might consider an awkward misalignment of our planet. Earth's axis is tilted about 23½° with respect to our orbit around the Sun. That means that the plane drawn by Earth's orbit, called the ecliptic, is tilted with respect to the planet's equator. And because from our perspective the Sun follows the ecliptic in its path through the sky over the course of a year, each day the Sun's highest point in the sky moves depending on the time of year. For a skywatcher at north temperate latitudes, such as in the continental United States, the effect is to make the Sun appear to creep higher in the sky each day from late December to late June, and back down again from late June to late December. An equinox comes when the Sun is halfway through each journey.

The Earth's axial tilt is why we have seasons. When the planet is on one side of its orbit, the Northern Hemisphere is tipped sunward and gets heated by more direct solar rays, making summer. Six months later, when the planet is on the opposite side, the Northern Hemisphere is tipped away from the Sun, and the slanting solar rays heat the ground less, creating winter.

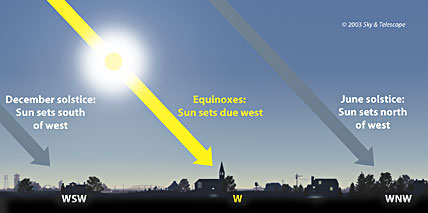

The Sun rises due east and sets due west on the equinoxes in March and September. At other times of year it comes up and goes down somewhat to the north or south. This illustration is drawn for mid-Northern latitudes.

This celestial arrangement makes several other noteworthy things happen on the equinox date:

- In the Southern Hemisphere, September's equinox marks the start of spring, and the March equinox marks the start of fall.

- Day and night are almost exactly the same length; the word "equinox" comes from the Latin for "equal night." (A look in your almanac will reveal that day and night are not exactly 12 hours long at the equinox, for two reasons: First, sunrise and sunset are defined as when the Sun's top edge — not its center — crosses the horizon. Second, Earth's atmosphere distorts the Sun's apparent position slightly when the Sun is very low.

- The Sun rises due east and sets due west (as seen from every location on Earth). The fall and spring equinoxes are the only times of the year when this happens.

- If you were standing on the equator, the Sun would pass exactly overhead at midday. If you were at the North Pole, the Sun would skim around the horizon as the months-long polar night begins. Richard E. Byrd wrote eloquently in his 1938 book Alone of the Sun as it dove into the long Antarctic night as seen from Advance Base, 80°08'S, 163°57'W:

Huge and red and solemn, it rolled like a wheel along the Barrier edge for about two and a half hours, when the sunrise met the sunset at noon. For another two and a half hours it rolled along the horizon, gradually sinking past it until nothing was left but a blood-red incandescence. The whole effect was something like that witnessed during an eclipse. An unearthly twilight spread over the Barrier, lit by flames thrown up as from a vast pit, and the snow flamed with liquid color.

3

3

Comments

Russ F

September 20, 2013 at 12:46 pm

Autumn begins on September 1st. Meteorologic as in weather and climate. Look it up: http://www.wmo.int/pages/index_en.html

We here should know that the autumnal equinox occurs IN autumn. It is an ASTRONOMICAL event - NOT any 'official beginning' - of either fall or spring! The sun angle has been decreasing for all of the northern hemisphere since the summer solstice. Summer, of course, began on June 1st.

http://weather.weatherbug.com/weather-news/weather-reports.html?story=5429

Weather & climate - nothing to do with astronomy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lou J

September 22, 2013 at 11:55 am

Russ, you make a good point. However, in most cases the astronomical events do signify the 'official' beginning of the seasons. Of course, it depends on your source and it is natural for meteorologists to mark the changing of seasons differently to coincide better with temperature and climate variations. Astronomers are well aware of the lag between the astronomical events and the warmest or coldest weather. You should not find it surprising that an astronomy publication would choose to use astronomical events to mark the seasons. Most calendars published in the U.S. use these dates as "official" beginnings of seasons as well. In any case, it has everything to do with astronomy, whether or not we use the specific events/dates or not. All dates based on any calendar are astronomical, as our calendars are based on Earth's orbit around the Sun and the Moon's orbit around Earth. In fact, these particular dates are much less arbitrary than picking the first day of the months because they signify distinct astronomical events.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Frank Reed

September 22, 2013 at 11:56 am

Russ, the standard definition of the seasons which has Fall (Autumn) beginning this afternoon, Sep. 22, is an ancient one, and we are stuck with it. It's not going away. You call it an astronomical definition, but I would even say that our traditionally-defined seasons are a relic of astrology, rather than astronomy. The seasons begin at the instant the Sun enters a particular "sign". These events have only minimal astronomical significance. I do like the meterological seasons, which have Autumn starting on September 1, but they, too, are a bit arbitrary. Why the first of the month? Personally, I prefer to tell people that the seasons (in weather terms) start on the 7th of the corresponding month. If you divide the year up by temperature into quarters, for most of the areas that interest me personally, you find that the coldest day of the year is right around January 21, the hottest around July 21, and the beginnings of the seasonal quarters are then Sep. 7, Dec. 7, March 7, June 7 (or thereabouts). The seasons lag the Sun by just about one month. And of course those meteorological seasons match up pretty well with our civil seasons, too. Summer ends on Labor Day here in the US (and Labor Day happens to have the nice habit of bouncing around in the first week of September from one year to the next). The beginning of civil summer is a little harder to define, but schools let out and beaches open sometime around the first week of June. So again, we actually use seasons in practice that do a pretty good job of matching the meteorology rather than the astrology/astronomy. But the latter definition of the seasons is traditional, and these dates are objects of popular celebration. Even the obvious discrepancy yields entertainment: how many times have you heard someone say in early December, "Look at all this snow... and it's still two weeks until the beginning of winter!"

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.