Now is the time to track the secret space plane X-37B on its OTV-4 mission.

Boeing / Paul Pinner

Step outside on any clear night at dusk during twilight hours and watch the sky for a few minutes, and you’ll notice swiftly moving “stars,” sentinels of our modern Space Age.

Some are regular satellites. (Folks at public star parties are always amazed to see satellites with their own eyes!) But most of what you’re seeing are actually discarded boosters in low-Earth orbit, and more than a few are clandestine spy satellites.

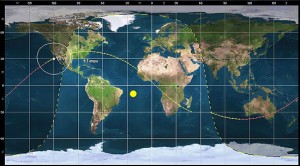

One of the more intriguing missions to track from your backyard is the U.S. Air Force’s X-37B. The USAF owns two X-37B spacecraft, and the current Orbital Test Vehicle 4 (OTV-4) mission is the fourth overall for the program. Launched from Cape Canaveral on May 20, 2015, OTV-4 orbits Earth once every 91 minutes in a 196-mile (315-km) altitude orbit. Its orbit is inclined 38° from Earth’s equator, ensuring that the craft is visible from latitude 45° north to 45° south.

As with a majority of classified U.S. Department of Defense missions, NORAD doesn’t publicly publish the orbital parameters for the X-37B. (The launch was broadcast live, however.) Once launched, tracking the mini space plane becomes the pursuit of dedicated satellite-watchers worldwide. You can trace this legacy all the way back to the original Project Moonwatch, which first tracked Sputnik 1 after its historic first orbit in 1957.

“In the time of Moonwatch, the network of amateur observers was a (if not the) most prominent source of tracking information on new objects launched,” says veteran satellite watcher Marco Langbroek. “Moonwatch and our modern network both make available data on objects on which otherwise very little data would be (publicly) available.”

Volunteer satellite hunters have confirmed — and sometimes refuted — launch claims by countries with largely veiled space programs, such as North Korea and Iran. They also recently tracked the maneuverings of the extra mystery payload Russia launched aboard the Cosmos-2496 satellite and which is suspected to be testing either in-orbit refueling or ”satellite-killer” tech.

A Mini Space Shuttle

Orbitron. Used with permission.

The X-37B is a direct descendant of Boeing’s X-40 project. A miniature space plane one-fourth the length of the U.S. Space Shuttle, the X-37B launches atop an Atlas V rocket and lands like an aircraft. Thus far, landings have occurred unannounced at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, though future missions (and perhaps OTV-4) may land like the Space Shuttle at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for rapid reprocessing and launch. The X-37B is only the second space plane — after the Russian Buran, which orbited the Earth once on November 15, 1988 — to perform an automated landing. It also holds the duration record for a space plane in orbit, having spent nearly 675 days in space during OTV-3.

OTV-4 is also notable in that, for the first time, the Department of Defense alluded to at least a portion of what the craft is doing during the mission: in addition to testing materials in space for NASA, it’s also demonstrating the use of Hall-effect thrusters as part of the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) satellite program, a strategic communications system being built by Lockheed Martin. Hall-effect thrusters will replace the troublesome liquid-apogee engines on AEHF satellites.

Hunting the X-37B

Greg Roberts

On a high pass straight overhead, the X-37B can reach around magnitude +3, similar in brightness to the stars that make up the constellation Aries the Ram. But more typically it gleams around magnitude +3.5, and it can drop to as faint as magnitude +5 at bad phase angles, says South African-based, long-time satellite tracker Greg Roberts.

We’ve seen the X-37B flare a few magnitudes in brightness on a zenith pass from here in central Florida, perhaps from sunlight glinting off the deployed solar arrays often depicted in artist’s conceptions.

“The current mission is in an orbit that makes it pass along (almost) the same ground track every two days,” says Langbroek. “That repeating ground track is something normally associated with Earth reconnaissance missions.”

Tracking and sighting opportunities for the X-37B are freely available and published publicly on many websites, including Heavens-Above. Heavens-Above is a great website to use to predict passes of satellites from your location, including the X-37B. Successfully spotting a satellite pass is as simple as knowing when it will occur, how bright it will be, and what direction it will be moving.

I also like to use the Orbitron satellite tracking program, as I can run it on a laptop in the field sans internet connection. Just make sure that the Two-Line Elements (TLEs) are up to date, as satellite orbits do change over time, mostly due to atmospheric drag. The SeeSat-L message board is also a long-standing source of discussion among volunteer satellite trackers.

Catching Satellites on Camera

You can also image satellite passes.

“I use a wide variety of equipment — all video or photographic — and as to what equipment I use, I decide prior to an observing session and select the best suited,” says Roberts. “If I have to do a planar search, then I go for relatively wide-angle fields, but if it’s straight positional work and the current orbit is known, then I use narrower fields of view.”

Roberts typically uses a camera with a 50- to 200-mm focal length for objects in low-Earth orbit, though he also employs a 10-inch aperture telescope to catch objects in medium-Earth and geosynchronous orbits. “My all-round favorite is a 4-inch f/2.6 refractor,” he adds.

Starting out imaging satellites is as simple as doing time-exposure shots of the sky with a tripod-mounted DSLR camera and letting the satellite “burn in” a streak as it slides silently by.

If you want to catch the X-37B, you have several weeks to try. Initial discussion by the USAF during the OTV-4 launch stated the mission would last a minimum of 200 days, which would place a possible landing in the first week of December at the absolute earliest.

Below, watch a video of OTV test flights (no sound). Credit: United States Air Force.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.