News has been sparse in recent weeks about Phoenix, NASA's newest Martian lander, and that probably suits the craft's handlers just fine. They've been working steadily but carefully to squeeze the most science of out a mission that will likely end once winter sets in a few months from now — and the clock is ticking.

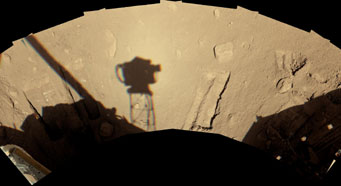

Phoenix's 7.7-foot-long robotic arm has dug plenty of trenches since the lander arrived in late May. In the areas at right, water ice lies just a couple of inches below the surface. The covering of dust is much deeper at left.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona / Texas A&M Univ.

Back on August 29th, Phoenix surpassed the 90-day milestone of its primary mission. I hesitate to say "completed" because, for all this lander has accomplished so far, a major objective still needs to be checked off the "to do" list: analyzing the water ice that lies abundantly beneath its footpads.

The ice has tantalized scientists since the first days after landing, when it became clear that plenty of the white stuff was within reach of Phoenix's 7.7-foot-long robotic arm. But getting scoopfuls of it (from a trench dubbed "Snow White") into the experiment hoppers hasn't been easy. The mix of icy shavings and soil particles clings tenaciously to the inner surfaces of the arm's scoop, and the Phoenix team is still working on a better delivery technique. Rumor has it they'll try again next week.

But other aspects of the mission are going well. Ice-free dirt samples have made into the tiny ovens of the Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer (TEGA) and another three samples to the lander's miniaturized wet-chemistry laboratory (WCL). Daily weather measurements are piling up — those should start getting really interesting now that northern summer is over and the Sun has started dipping below the horizon each night.

As of early September, Phoenix's deepest excavation was a 7-inch-deep trench dubbed "Stone Soup" (at bottom center). The small rock at right, nicknamed "King's Horses," is about 8 inches (20 cm) across.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona / Texas A&M Univ.

The science team has gotten a green light from NASA managers to keep digging, sniffing, and tasting through the end of September, but how much longer Phoenix might last after that is anyone's guess. I'm sure plenty of bets are on the line at the science operations center in Tucson, Arizona, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Phoenix sits amid polar terrain with a subtle polygon-shaped texturing that betrays how the ice is distributed just below the surface. Think of a sheet of bubble wrap (the kind used for shipping packages), and you'll get the idea. In some spots mounds of ice about a yard across lie barely covered with ruddy dirt, whereas the dirt layer extends deeper in the shallow troughs between them.

Recently Phoenix's excavations have shifted to a trough that's within arm's reach, and last weekend the robotic arm gathered up a sample dug from a trench (nicknamed "Stone Soup") about 7 inches (18 cm) deep.

By sticking this probe into the ground and passing electricity among the four tines, Phoenix can determine the water content of the Martian surface — which turns out to be extremely dry.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona / Texas A&M Univ.

One puzzling result followed a test of the soil's water content using a fork-like probe on the end of its sampling arm, which passes electrical current through the surface layer. It seems the topmost dirt is dry as, um, dust — even though there's water vapor in the air above it. "The relative humidity transitions from near zero to near 100% with every day-night cycle," notes JPL investigator Aaron Zent in a September 4th press release, "which suggests there's a lot of moisture moving in and out of the soil."

Puzzled or not, Phoenix's scientists seem to be having fun — at least as evidenced by the whimsical names they assigned to landmarks in the lander's trenching area. A few others, besides Snow White and Stone Soup, are a sample called Baby Bear (dug from Dodo-Goldilocks), the Upper and Lower Cupboards, Wicked Witch, and Ichabod.

All these giddy names make me wonder just how much sleep the science team got back in May and June, when they reset their body clocks to coincide with the Martian day (24.6 hours long). Now they're back on a more restful 9-to-5 schedule, but the name game hasn't stopped. The last sample, delivered to a WCL cell just a couple of days ago, was dubbed Golden Goose 2.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.