When news breaks in the world of astronomy, we try to get word of that to you here as quickly as possible. Our motto has been: “If it’s a big story in astronomy, you should be able to find out about it here.”

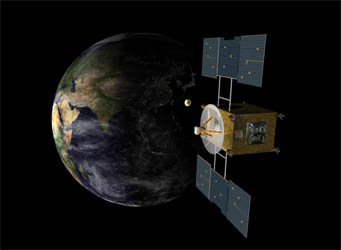

A protrayal of Hayabusa's long-awaited return to Earth on June 13th, just after release of its descent capsule.

NASA / JPL / C. Waste / T. Thompson

For example, in the past year you’ve read here about the heroic effort to get the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa ("Falcon") back to Earth. Before, during, and after its brief touchdown on asteroid 25143 Itokawa in November 2005, the craft suffered several crippling malfunctions — solar-cell panels damaged by a powerful flare, complete failure of its stabilization system, an internal fuel leak, loss of thruster rockets and three of its four ion-drive engines, partial battery failure — any of which might have doomed the mission.

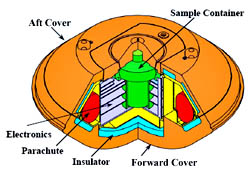

Yet somehow the mission’s engineers have coaxed Hayabusa back to Earth’s doorstep, albeit two years later than planned. Tucked inside the spacecraft is a small capsule, only 16 inches (40 cm) across, that might contain bits of the asteroid, and this triumph-over-adversity saga won’t be complete until that capsule safely parachutes into the team’s waiting arms.

Hayabusa's sample-return capsule is just 16 inches (40 cm) across and weighs 38 pounds (17 kg). Scientists hope that tiny bits of an asteroid are safely stored inside.

JAXA / Yukio Shimizu

All that said, the truth is that I’ve kept mum about some aspects of this developing story. Take, for example, the landing date. A couple of days ago, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) finally divulged the date and time: June 13th at about 14:00 Universal Time (11 p.m. in Japan).

More true confessions: while I did tell you that the landing would take place in Australia’s remote Woomera Test Range, what I wasn’t able to add — until now — is that I’ll be there to welcome Hayabusa home.

Some of you know that I’m teaching astronomy at the Dexter and Southfield Schools in Brookline, Massachusetts. This private, K-12 institution is home to the Clay Center Observatory, which boasts a remarkable 25-inch Ritchey-Chrétien telescope. The observatory’s director, Ron Dantowitz, has occasionally worked with NASA to perform specialized imaging and spectroscopy of objects ranging from Space Shuttle launches to outbursts from meteor showers.

Researchers aboard a NASA aircraft tracked the atmospheric reentry of Stardust's sample-return capsule in the predawn darkness over Utah on January 15, 2006.

NASA / M. Taylor / Utah State Univ.

For the Hayabusa recovery, Dantowitz has once again teamed up with Peter Jenniskens of NASA's Ames Research Center and the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. Jenniskens has assembled an international team of researchers to record Hayabusa’s sample capsule (and a half ton of fragments from the main spacecraft) as they plunge through the night sky over Woomera at 7½ miles (12 km) per second.

Satellites reenter the atmosphere all the time, but rarely from the depths of interplanetary space and at such a high velocity. (One recent example was the return of Stardust in 2006.) So think of Hayabusa’s reentry as a whopping-big, one-of-a-kind meteor. Knowing which parts glow incandescent and ionize at which altitudes has tremendous scientific value.

Among the researchers who'll record Hayabusa's return to Earth are (from left) James Breitmeyer, Yiannis Karavas, and Brigitte Berman — students at the Dexter and Southfield Schools in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Ron Dantowitz

During the reentry a DC-8 aircraft crammed with the researchers and their equipment will be circling near the entry track. Other members of the Clay Center team will be staff astronomer Marek Kozubal and two talented (and very lucky) students: Brigitte Berman and James Breitmeyer. Meanwhile, a subset of team will be positioned on the ground to record the reentry. That’s where I come in: I’ll be helping a third student, Yiannis Karavas, take visible and near-infrared spectra of the white-hot spacecraft.

As you can imagine, we’re all really excited about this — and for now I’m hard at work reacquainting myself with the southern sky.

4

4

Comments

Mark

April 25, 2010 at 3:37 pm

I'm a bit confused. In your article of Nov 29 2005 "Hayabusa Hits Paydirt" you state that "At about 7:30 a.m. Japan time, Hayabusa (Japanese for "falcon") briefly touched down on 25143 Itokawa in a flat, relatively featureless area informally dubbed Muses Sea. Then it quickly fired two metal pellets into the surface, timed just 0.2 second apart, and collected some of the dust kicked up by the impacts." In the same article it was also stated that on Nov 20th during the first sampling attempt that it did not fire the pellets.

But in a later article on March 30th 2010 you said that "Hayabusa failed to fire two small tantalum pellets designed to kick surface material into a collection cone."

So I'm a bit confused. Did it fire the pellets and sample the dust or not?

Not a criticism just genuinely interested in a fascinating story of perseverence and determination to get this craft back to Earth.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lee

April 26, 2010 at 5:49 pm

You call it "NASA's SETI Institute in Mountain View, California"... but the SETI Institute is not owned by or run by or part of NASA in any way.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lawless J.

April 28, 2010 at 2:00 pm

I'm wondering how these engeneers were able to put their hands back on the probe . It's a marvellous job and I hope they will succeed to recover their priceless sample container .

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Faye Kane, homeless brain

May 12, 2010 at 10:32 am

Kelly, I've liked your work over the years, but please answer Mark's question about whether or not the pellets were fired, and if not, why not, and where did the sample material come from?

For that matter, why didn't they use a more reliable method that would return more material, like firing a slug with slits in it (where material would collect) into the asteroid, then retrieving it with an attached wire?

--faye kane, idiot savant

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.