Though Saturn’s Great White Spot faded by the end of 2011, infrared telescopes have revealed the storm's long-lasting impact.

The Eastern seaboard hunkered down yesterday as Hurricane Sandy (aka Frankenstorm) barreled ashore. Even after hitting land, Sandy was still moving at a steady 28 mph, carrying sustained winds of 85 mph. Coastal areas flooded, including parts of New York City, and millions lost power. The storm surge along with the accompanying rain and gales might cost East Coast states up to $20 billion in total damages, much more than originally anticipated.

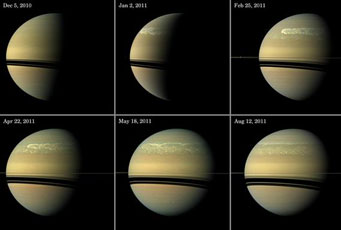

The Great White Spot erupted in late 2010 and captivated professional and amateur attentions for a year as it evolved from a white spot to a white ring fully encircling the planet before it dissipated by late 2011.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI

Faced with the wreckage of a hurricane, it’s hard to believe that Frankenstorm barely registers on the solar system’s weather scale. Saturn’s Great White Spot would have dwarfed little Sandy, and recent research shows that the tempest is continuing to wreak havoc in the planet’s upper atmosphere almost two years after it started.

Leigh Fletcher (University of Oxford) and his colleagues observed the evolving storm using Cassini, the Very Large Telescope in Chile, and NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) at Mauna Kea, revealing the full extent of the storm’s impact on the gas giant’s upper atmosphere.

When the Great White Spot erupted in late 2010 (May issue, page 20), the spectacular cloud display riveted the attention (and observing capabilities) of amateurs and professionals alike. The storm raged for roughly a year, encircling the planet and discharging lightning almost continuously. Warm, moist air rushed upward through the troposphere with speeds up to 335 mph, about four times faster than Hurricane Sandy’s winds, and the white monster’s head surged against Saturn’s jet streams at roughly 60 mph, twice the speed of Frankenstorm as it approached New Jersey.

Infrared telescopes following up on Saturn's Great White Spot — which faded by the end of 2011 — found a long-lasting infrared vortex spawned by the great springtime storm. The image shows the low-resolution infrared spot superimposed on a visible-light image of Saturn taken by Cassini.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI / ESO / IRTF / ESA

The Great White Spot — that is, the sunlight scattered off of clouds in the troposphere — had largely faded away by the end of 2011. But infrared views are now showing the storm’s true aftermath. While the cloud decks of the troposphere roiled below, the storm’s energy rippled upward to disturb the quiescent stratosphere hundreds of kilometers above. Even after the stormy white clouds dissipated, an infrared vortex continued to swirl in Saturn’s upper atmosphere.

In Earthbound thunderstorms, hot air rises and cooler air sinks, a boiling motion that often leads to an effect called “gravity waves.” (This effect is very different from gravitational waves!) While air usually moves horizontally to the ground, gravity waves move air up and down instead, much like waves on water. Gravity waves carry energy from below into the upper atmosphere, and Fletcher and his colleagues think that’s exactly what happened in Saturn’s atmosphere.

What began as a tropospheric storm (similar to a thunderstorm on Earth) soon became not one, but two spinning vortexes in Saturn’s stratosphere. Rather than cooling down and dissipating, the warm, whirling airmasses soon merged into a single vortex that, for a brief time, was even bigger than Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

Watch the video below to witness (from the side and from above) the two vortexes spawned by the Great White Spot. Unlike the clouds seen via scattered sunlight, which drift to the right in the video, the infrared-bright vortexes drift to the left following tropospheric winds. The first moves slowly at about 14 mph. The second travels with the head of the Great White Spot at 55 mph, catching up to merge with the slower vortex. Since the merger the giant beacon has shrunk and cooled a bit, but it’s still making its way around the planet at 55 mph as of the last reported observation in May 2012. Fletcher and his team expect the beacon to fade away by the end of next year, long outlasting the visible-light storm.

1

1

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

November 2, 2012 at 12:08 pm

I watched the video of the infrared hotspots circling Saturn and swallowing one another several times. Strangely hypnotic. Superimposing the infrared images on high-resolution visible light images was a very smart design decision. More educational eye-candy from JPL.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.