Although flight controllers were worried that Mars-orbiting spacecraft might be harmed by the comet's close approach, nothing happened — and unique scientific observations are now streaming back to Earth.

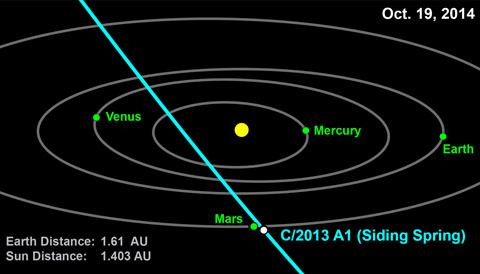

Six months ago, flight controllers on both sides of the Atlantic were worried about how close Comet Siding Spring (C/2013 A1) was coming to Mars and what might happen when it got there.

NASA / JPL / Horizons

NASA's teams decided to take the proactive route by altering the paths of their three orbiting spacecraft: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Mars Odyssey, and the just-arrived the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft. These tweaks put all three on the opposite side of the planet during the window of greatest danger, which computer models suggested would occur 90 to 100 minutes after the comet came closest to Mars.

Meanwhile, dynamicists at the European Space Agency took a wait-and-see approach. A plan was drawn up to have the agency's Mars Express orbiter briefly duck behind Mars as well.

However, because spacecraft is low on fuel and spends most of its orbiter relatively far from Mars, and because the comet's activity waned as the encounter neared, no adjustment was necessary. In fact, earlier this month mission managers decided not to turn the spacecraft so its big dish antenna could serve as a partial shield to protect the craft from cometary particles.

Instead, the good news is that all five Martian orbiters (including India's Mars Orbiter Mission) survived the comet's encounter without incident. Here are NASA's post-encounter status reports for MRO, MO, and MAVEN. Here's the latest word about Mars Express. (There's no word yet on the status of MOM or the observations it gathered.)

NASA / CIOC

Early Results from the Comet Encounter

Now that the comet has come and gone, at least in the neighborhood of Mars, planetary scientists are eager to analyze all the data these and other spacecraft are gathering about the unprecedented close flyby.

One of the most anticipated results came from the powerful HiRISE camera aboard MRO. Alfred McEwen, the University of Arizona researcher who heads the camera team, described the picture-taking attempt as "like imaging a speeding bullet while riding a roller coaster." Concern heightened when, 12 days before the encounter, test images showed that the comet wasn't quite in its predicted location.

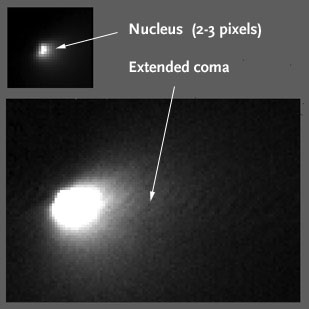

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona

But everything worked just fine, and HiRISE images taken during the encounter show that the nucleus of Comet Siding Spring is only two or three pixels across. So it can't be more than 0.5 km (about 1,500 feet) across — about half the size estimated from earlier observations. Still, this is the first time anyone has seen the nucleus of an Oort Cloud comet. McEwen and his team hope to derive the albedo, or reflectivity, of the icy nucleus (likely very, very dark) and its rotation rate.

The high-resolution camera on ESA's Mars Express wasn't able to resolve the nucleus, but its images of the comet's coma and tail will still be valuable. Word is that those data are on the ground but will take a few days for a quick-look analysis.

A very different perspective came from NASA's enduring rover, Opportunity, which looked up into the Martian night and spotted the comet from its perch in Merdiani Planum. Curiosity took some snaps too, but those haven't been released yet.

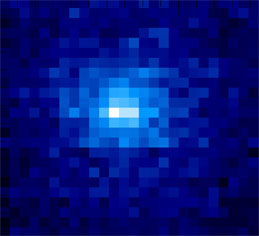

NASA / LASP / Univ. of Colorado

Another intriguing result is to what extent, if at all, gases from the comet's coma impinged on the upper Martian atmosphere, effectively contaminating it. Here's where the recent arrival of MAVEN and MOM, both equipped to make such observations, proved serendipitous. Earlier today the MAVEN team released an ultraviolet image that recorded a vast cloud of hydrogen atoms (derived from water molecules) in the comet's coma.

Other MAVEN results might not emerge so quickly. Measurements of hydrogen (and its heavier isotope deuterium) in the planet's upper atmosphere must take into account a pulse delivered recently by a strong coronal mass ejection from the Sun. "It's our first data taken in mapping mode, and we'll have to understand our instruments," explains MAVEN principal investigator Bruce Jakosky (University of Colorado). "The bottom line is that I can't promise yet when we'll have results — it may be very quickly, or it may take a while."

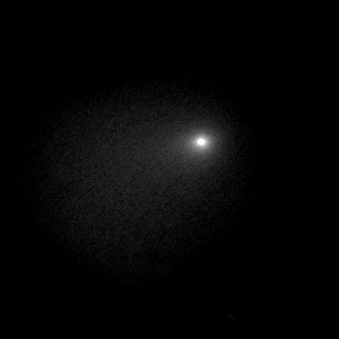

The Hubble Space Telescope also recorded the comet as it neared Mars. (Although the planet is slowly nearing the Sun from Hubble's orbital perspective, the planet is still separated widely enough, by about 60°, for the telescope to follow the action.)

The image at right shows a near-infrared view captured by the orbiting observatory on October 19th. It was also used in a composite image that NASA pulled together by adding a color image of Mars taken separately by HST. But the result looks very unnatural, especially the simulated starfield. Have a look and see if you agree.

Meanwhile, lots of cameras here on Earth were pointed in the direction of the Red Planet and its temporary companion, and amateurs (as usual) came up with many dramatic views of the Red Planet and its cometary companion. Two of the better ones are below.

© SEN / Damian Peach.

Gerald Rhemann / Sky Vistas

Our special issue, "Mars: Mysteries & Marvels of the Red Planet," is loaded with spectacular photos and a must-read for anyone interested in this intriguing neighboring world.

4

4

Comments

October 24, 2014 at 5:34 pm

RE: Comet Siding Spring

Does anyone know why we aren't getting any pictures from the surface of Mars? I cannot imagine that the rovers Opportunity and Curiosity didn't get some amazing shots of a comet only 88,000 miles away.

Perplexed in Oregon

You must be logged in to post a comment.

October 25, 2014 at 9:56 am

This certainly was not the first time a comet was observed from another planet. NASA's Pioneer Venus Orbiter made UV observations of Comet Halley in February 1986 since Venus was in a better position than the Earth to observe Halley (although at a distance of 40 million km, Halley wasn't anywhere near as close a pass as Comet Siding Spring's pass by Mars). And originally the Soviet VEGA mission to Comet Halley (when it was known as "Venera 84") started as studies for similar observations from Venus orbit. Of course the mission changed radically when it was discovered that Comet Halley could be reached by the Venera spacecraft after a Venus flyby.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

October 25, 2014 at 8:48 pm

I wasn't aware of these other observations. Very interesting. However, my original question remains.

Why do you think that NASA isn't releasing any photos taken by Opportunity or Curiosity from the planet's surface?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

October 27, 2014 at 1:08 pm

I wasn't addressing your question (which apparently wasn't posted when I made my original comment). However, to address your question directly, the chances that either rover would catch a usable image of Comet Siding Spring was considered pretty low. Yes, the comet was close but it didn't produce a lot of dust (which is what reflects the light for us to see the comet's coma and tail), the illumination is half that at Earth's distance, what light is coming from the comet is spread over a large area of the sky resulting in a very low surface brightness. All of this combined with less than ideal viewing conditions from the rover sites (i.e. just after sundown or just before sunrise) and the fact that the rover camera's were not designed for low surface brightness astronomical imaging means that it is unlikely that the comet would be spotted by the rovers.

All that being said, NASA *HAS* released a couple of images of Comet Siding Spring acquired by the decade-old Opportunity rover that are available at the following NASA web site:

http://mars.nasa.gov/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1738

They are very poor but they do show the comet about half way between Alpha and Omicron Ceti at a distance of 139,500 miles

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.