So far, so good... After a leisurely 4½-day coast through space, NASA's two newest recon robots reached the Moon on June 23th and then bid each other adieu.

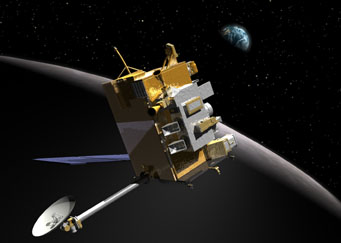

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is equipped with seven instruments that will thoroughly map the Moon for at least one year.

NASA

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter fired a braking rocket at 6:27 a.m. EDT (10:27 Universal Time) and slipped into a looping orbit that will carry it over the lunar poles. Four additional burns are needed to tighten the circuit into a "commissioning orbit" 20 by 135 miles (20 by 216 km) high, and in two months that will shrink further to final circular orbit just 30 miles (50 km) above the surface. From that vantage seven instruments will map and survey the desolate landscape below for at least one year.

Meanwhile, a second probe remains attached to the liquid-fueled Centaur rocket that helped launch the mission. Aided by the Moon's gravity during its brief swingby, the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, swung into a much wider polar loop and, technically, is still orbiting Earth every 37 days.

A snapshot of the Moon taken June 23, 2009, by the visible-light camera aboard NASA's LCROSS spacecraft.

NASA

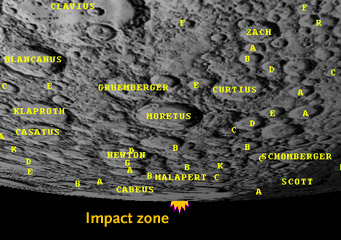

Three loops from now, on October 9th, mission controllers will guide the emptied Centaur, followed 4 minutes later by LCROSS, into a permanently shadowed crater near the south-polar feature Cabeus. Pummeling the lunar surface at 1½ miles (2½ km) per second should raise giant clouds of debris, perhaps entraining some of the water that theorists believe lies frozen in the lunar shadows.

Mission managers plan to select the exact target about a month ahead of time. For now, the impacts are scheduled for within a half hour of 11:30 Universal Time (7:30 a.m. EDT, 4:30 a.m. PDT).

On October 9th, the LCROSS spacecraft and its spent Centaur rocket will crash into a permanently shadowed crater near the Moon's south pole. Amateur astronomers with large telescopes might be able to see the resulting cloud of debris.

That timing is crucial, as the rising plumes need to be in view of the arsenal of observatories atop Mauna Kea and the western U.S., the Hubble Space Telescope, and a Swedish astronomical satellite named Odin.

(Why Odin, you might ask? Its two instruments are well equipped to detect faint wisps of water vapor and other volatile compounds.)

This closeup of the Moon's south pole closely matches the lunar phase (waning gibbous) on October 9, 2009, when NASA ground controllers will force the LCROSS spacecraft and a Centaur rocket to crash into a shadowed crater at the pole.

Sean Walker

It's hard to gauge just how bright the impact clouds will be, but some calculations suggest 4th magnitude isn't out of the question — and that gives well-equipped amateurs a shot at seeing or recording the splashy event.Interested? For now you can learn more from the LCROSS team tasked with coordinating the observations.

SkyandTelescope.com plans to provide full details about where, when, and how to watch. You can also read more about this exciting mission in Sky & Telescope's June 2009 issue.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.