During a recent science conference discussing Messenger's results from Mercury, investigator Shoshana Weider (Carnegie Institution of Washington) commented, "Short of landing on the surface, picking up a rock, and bringing it home, the instruments on Messenger that characterize chemistry are the best we're going to get."

A dramatic splash of rays surround Mena, a fresh crater on Mercury about 10 miles (15 km) across. Dynamicists believe that such high-velocity impacts should have blasted many pieces of the innermost planet into space, some of which should have reached Earth.

NASA / JHU-APL / CIW

Well, Shoshana, you might still get to hold such a rock someday.

According to a 2008 analysis by Brett Gladman and Jaime Coffey (University of British Columbia), chunks of Mercury should be lying somewhere on Earth right now. The dynamicists conclude that 2% to 5% of the debris blasted by impacts off the surface of Mercury at or above escape velocity (2.6 miles per second) should reach Earth within 30 million years.

Their numbers suggest that Mercurian meteorites should be roughly one third as common as those from Mars, for which the count now stands at 60. Gladman conservatively suggests that at least a half dozen stones should be lying around somewhere on terra firma.

Meteorite collectors would value a Mercurian meteorite above all others, likely fetching $5,000 or more per gram, so they've been on the lookout for one. A few years ago, meteoriticists had speculated that the best existing match to Mercury were a rare handful of ancient, basalt-rich stones known as angrites.

But even before Messenger's arrival, ground-based astronomers had concluded that Mercurian surface rocks contained very little iron — strange indeed, given that the innermost planet has an iron core that takes up 80% of its diameter and more than half of its volume!

"At that time," comments geochemist David Blewett (Applied Physics Laboratory), "people were expecting Mercury to have a composition more like a lower-iron version of the lunar highlands. We now know that it's much different than that." After nearly a yearly scrutinizing the planet from orbit, Messenger has confirmed that iron is in short supply at the surface.

The Cumberland Falls stone, which fell in 1919, is one of only 62 recognized samples of aubrite meteorite. These contain very little iron and are similar — but aren't an exact match — to the composition of Mercury's surface.

Claire Houck / Wikipedia Commons

Instead, the compositional clues suggest that a Mercurian meteorite would be an igneous rock — or perhaps a fused breccia of different rock types — rich in magnesium and volatile elements (especially sulfur and potassium). This closely matches the composition of another rare meteorite group, the aubrites. Also known as enstatite achondrites, aubrites are igneous rocks dominated by the iron-free mineral enstatite (Mg2Si2O6).

But aubrites aren't from the innermost planet. For one thing, they're too reflective — anything coming from Mercury would be much darker, tinted by some yet-to-be-identified compound that's seen widely in Messenger's images. It might also smell faintly of sulfur, appear heavily shocked, exhibit significant exposure to cosmic rays, and might even be slightly magnetic. Such characteristics would certainly have come to the attention of hunters and collectors, and it's safe to say that none of the world's 40,000 well-documented meteorites are from Mercury.

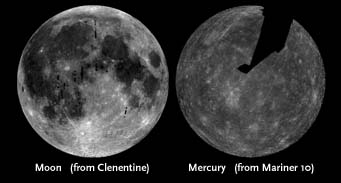

On average, the surface of Mercury is about 15% darker at visible wavelengths than is the nearside of the Moon. (These images are not shown at the same scale.)

NASA / JHU-APL / CIW

Yet dynamical probabilities argue otherwise, so why haven't such samples been found? Gladman and Coffey didn't address how chunks of rock might get blasted off the Mercurian surface, only that the high collision velocities of asteroids and comets should make it easy to do so.

Maybe the launch mechanics aren't understood well enough, suggests Jay Melosh, an impact specialist at Purdue University. "Perhaps at the very high speeds required for direct transfer, the fragments are simply too small," he says. "These ejecta have to be launched from the surface very close to the impact point — and perhaps our current models do not give very good results here." However, Messenger finds that big impacts on Mercury are accompanied by clusters of secondary pits, created by tossed-out debris, that are generally much larger — not smaller — than those around comparable lunar craters. "This fact is one of the current big puzzles about the Mercurian cratering record," Melosh concedes.

And so the search goes on for what will almost certainly be the most celebrated meteorite discovery since the finding of stones blasted from surfaces of the Moon and Mars a few decades ago.

14

14

Comments

Michael C. Emmert

January 6, 2012 at 12:58 pm

Don't meteor hunters generally test a candidate with a magnet to confirm that it's a meteorite? If it's a Mercurian meteorite they might have thown it away because of this. I would advise checking Antarctica, there are fields there where all rocks are meteorites.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Karl

January 6, 2012 at 2:47 pm

I have been in possession of a very peculiar rock for the last 45 years or so...It's quite small, but piqued my curiosity when I picked it up from the beach where I was doing some rock hunting. It was VERY light, compared to other stones its size! Roughly pyramidal in shape, weighing only a few grams, it seems to exhibit meteorite-like properties. It's very dark in colour and the surface shows what may be described as regmalypts. I don't know WHY I did this, but I brought a magnet near it and discovered it is definitely magnetic. (This was more than 45 years ago!)

Do you suppose I have a Mercurial Meteorite? Who should I contact?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris

January 6, 2012 at 6:47 pm

Karl, your stone doesn't sound like a meteorite. You said it was very light? I'm guessing by light, you mean it is light in comparison to other rocks? Even though achondrites are generally lighter than irons and chondrites, achondrites have roughly the same density as terrestrial igneous rocks (3g/cm3). Only the CI and CM chondrites have lower densities. You also say you found it on a beach. Of the 40,000+ meteorites, only one has been found on a beach (Southampton) and it was extremely weathered. The salt water at a beach is extremely destructive to meteorites, and the CI and CM meteorites mentioned, would disintegrate within a day, ruling out any light meteorite. The "regmaglypts" you describe, are these shallow depressions, like someone has lightly pressed a miniature thumb into putty, or are they more like little holes/circular depressions. A meteorite of only a few grams would have subtle, shallow regmaglypts. From your description of it as "VERY light", it's probable that your stone is full of tiny holes/vesicles, as this would explain the low density. Meteorites, contrary to popular belief, do not have holes or vesicles. They all, except for Martians, form in environments without gas to form the holes. Even Martians have vesicles that can only be seen with a scanning electron microscope. The only meteorites that have a holy look to them are a handful of Lunars. This is caused by gas implanted by solar wind expanding as the surface turns to liquid during the fiery passage through the atmosphere. In this case though, it's only the thin crust that has the holy look to it and they are still just as dense as other achondrites. From your description of your stone, it sounds like volcanically ejected basalt. When basalt is hurled into the air during an eruption, gas that was compressed inside it under the tremendous pressure underground, can expand quickly and the rock solidifies as a basalt pumice. Basalt can also be very dark and show an attraction too a magnet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris

January 6, 2012 at 10:37 pm

@Michael, Antarctic meteorite recovery is a challenging enterprise, however several countries such as Japan and the U.S. conduct annual expeditions to recover meteorites. The U.S.'s program, ANSMET (ANtarctic Search for METeorites) for instance, has recovered in excess of 17,000 meteorites in its 35 years of operation. The steep, mountainous terrain and ice cover that over centuries, migrates like glacial ice, causes meteorites to accumulate at low points. Private meteorite hunting in Antarctica is prohibited however. Article 7 of The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, prohibits the exploitation of mineral resources, except for scientific research. Magnets aren't used by meteorite hunters to the same extent nowadays as they once where. In fact, a number of scientists try to discourage the use of magnets by hunters because it erases the paleomagnetic field from the surface, necessitating the need to drill a deep core if they want to study the magnetic field of the parent body. The above mentioned ANSMET prohibits the use of magnets by its participants. Meteorites are generally identified by a number of other characteristics other than magnetism, such as fusion crust, regmaglypts, weight, texture and concretion cracks for example. A large number of meteorites including some Lunars, some Martians, arbrites, some ureilites, some angrites and a number of the HED's from Vesta among others, have all had many different specimens discovered despite the fact they show almost no attraction to a magnet. In fact, since many terrestrial rocks are strongly attracted to a magnet, the magnet test is probably one of the few tests in which a hunter might discard the stone if it where the only test it passed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nick

January 7, 2012 at 12:38 am

I thought I had something very interesting. For a background, These rocks includes; Medusa-effect like Mummified animal head/s solidified in Volcanic Ash and sorts of internal organs, fruit chunks, petrified tree limbs, etc., also a suspicious Miocene Armored mud balls in Three(3) different colors, Pleistocene coral, Rare earth, Nickel and other ores all pile-up and found on one side of the beach, together with Unclassified but oriented basaltic and other type of meteorites and impactite...,

Here's what I suppose something very different from my other UNWA's. Among the above finds, I only had one of this squarish and naturally sliced rock shaped and colored like Chocolate cake (as found). It had black surface on Three sides, Two side are brown and the last is made up of brown and shaded in black. Ironic of it is, that very side shows the solidified melting point. Flatter bottom bears pebble impressions, and had slight magnetic attraction. When polished, Matrix reveals grayish with faded black colors. At a size of a palm at 4.5x 3.75x 2.75, it weighted more than 1,600+ grams or 1.6++ kgs.

I apologized and please pardon my simple English. I hope I made the description clear and understandable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Karl

January 7, 2012 at 7:35 am

Thanks for the input, Chris! Perhaps I can clarify a little more - when I said "beach," in actuality it was beside a RIVER in southern Quebec. Nowhere near salt water. The apparent regmaglypts are shalow but well defined, and the entire stone has a glassy appearance. As well, it is attracted to a magnet.

If not a meteorite, where can I find out just what this curiosity might be? I've asked several rock collectors, and they're stumped. I've been keeping it as my "lucky rock" these past many years.

Thanks again!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris

January 8, 2012 at 8:09 pm

Probably the best starting point would be to join one of the online meteorite communities and ask for assistance there. A quick search for "meteorite forum" will bring you to a number of good choices, some of which even have an area dedicated to identification. Pick a site with the most activity if you want a prompt answer. When asking for help, it's important to post at least one good, clear photo. It's very important to make sure the subject is in focus, with good lighting/exposure and something for scale. Many people will come seeking help, but post a blurry, dark photo that assists no one. Most members who assist in identification expect that the person seeking assistance to have done at least some basic research and to explain, based on that research, why they think they have a meteorite. Basic research isn't difficult and a few simple tests can be done in any home. The first is magnetic susceptibility, which you've already done. 99.9% of meteorites are at least mildly attracted to a magnet. Also, take note and mention the density when describing it. This is very important to making an accurate identification. Next is fusion crust. Does the stone appear to have any remnant crust. Fusion crust is a dark, glass like coating usually no more than 1mm thick. In older meteorites, much of the crust may be missing, but their is usually some remnant of it. Then there is shape. Meteorites are irregularly shaped, but smooth. When a meteorite is ablating through the atmosphere, any sharp corner is worn away, leaving a rounded, smooth surface. Meteorites don't have sharp corners, apart from on broken surfaces after hitting the ground (these broken surfaces will lack any crust). Think of this shape as like a piece of ice melting in water.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris

January 8, 2012 at 8:10 pm

Next is the scratch test. You need to find some sort of rough, non glazed ceramic, like the back of a tile, or the underside of a toilet lid. Scratch lines on it with the rock and observe color. Meteorites leave very faint streaks of brown, to grey, yellow, or a very light red. If the color is a thick strong color like blood red or chocolate brown, then it is not a meteorite. The final test is to check the interior. To do this, grind away a small corner until you can see the interior. Don't worry about damaging the value if it turns out to be a meteorite. Only the most aesthetic of meteorites would loose value this way and a meteorite is going to have to be cut anyway, if you want it to be officially recognized (unrecognized meteorites really worth anything anyway). If you can see small specks of metal, as well as small circles of different colored rock (chondrules), then your off to a good start. People won't be able to definitively identify something as a meteorite based on a photo and description alone, but they will be able to rule something out with certainty if doesn't closely fit the bill. If it does look promising, they will be able to direct you on what further steps to take from there. I hope this helps and good luck.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

gnappi

January 9, 2012 at 3:18 am

"anything coming from Mercury would be much darker, tinted by some yet-to-be-identified compound that's seen widely in Messenger's images. It might also smell faintly of sulfur, appear heavily shocked, exhibit significant exposure to cosmic rays, and might even be slightly magnetic."

I bought a few years ago some meteorites on the internet and one of them fits that description perfectly! Can it be from mercury?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Karl

January 9, 2012 at 4:58 pm

You've provided me with a bounty of information, Chris! Thanks! I'll definitely be joining a meteorite forum or two. But first, I'll get all my ducks in a row and carefully photograph the rock from all possible angles, measure its density, weigh it, and do the scratch test.

OK, I just went into the bathroom and took off the toilet tank lid. The rock hardly makes a mark (streak) at all on the rough underside of the lid, and it's pretty faint. (Brownish.) I may be on my way to owning a genuine piece of Outer Space! LOL

Clear Skies!

Karl

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nick

January 12, 2012 at 9:53 am

Wow! I thought I had this kind of rock that fits the description of Basaltic composition of the aforementioned subject. As a Bonus, the rock itself shows beautiful pattern of flight orientation., I hope this is it?

Limitless skies, Nick

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Karl

January 17, 2012 at 2:56 pm

If anyone is still following this thread, I have posted pictures of my (suspected) Mercury Meteorite on PhotoBucket.

http://s161.photobucket.com/albums/t224/Gunrunner45/Meteorites/

The pictures are pretty much self explanitory, but if anyone needs to contact me for clarification, I may be reached at:

[email protected]

Hope everyone has Clear Skies!

Karl

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Aharonn17

June 20, 2020 at 2:00 pm

By any chance would the inside of the meteorite smell like sulfur the inside looking green, not be magnetic and look white On the outside and be poris as well. To me that doesn’t sound like a meteor but maybe you might think differently

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jonhough1

September 25, 2022 at 10:02 pm

I think I have one. Contact me and I'll send pics

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.