Over the course of ten years, a once-brilliant quasar seems to have stopped gobbling down nearby gas.

| Update Jan. 13, 2015: A new version of the paper corrects how long it would take for big changes in accretion rate to happen. Initially, LaMassa and colleagues calculated that such a change would occur over thousands of years, which we noted below would "dwarf human lifetimes." However, an updated calculation puts that estimate on decade timescales, which are perfectly consistent with the data. Nevertheless, the transition observed by LaMassa's team is rare, and this remains the most luminous and distant active galactic nucleus to undergo such a change. |

NASA / Dana Berry

Most large galaxies contain a central supermassive black hole. Some — such as the one in the Milky Way’s center — are dormant beasts. Others, known as quasars, outshine their host galaxies as they chow down on gas.

Black holes must transition from active to dormant status, but big changes should occur on astronomical timescales that dwarf human lifetimes. So when Stephanie LaMassa (Yale University) found two radically different spectra of an object measured just 10 years apart, she was shocked.

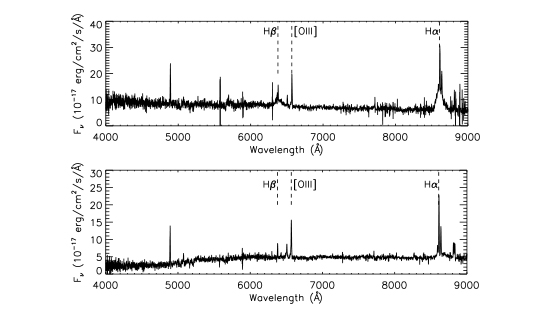

Most of quasars’ visible-light emission comes from the hot accretion disk that feeds the black hole. Orbiting gas clouds, heated and ionized by the disk, make their contribution to the visible spectrum in the form of emission lines. These wavelength-specific spikes of emission may vary in brightness, but they don’t generally change shape. Some lines are fat, spreading their emission over a wide range of wavelengths, while others are skinny. Typically, fat lines stay fat and skinny lines stay skinny.

The first spectrum, measured in 2000 with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, resembled a classic quasar: blue in color with broad emission lines. But the second spectrum, measured in 2010 as part of the BOSS Survey, didn’t exhibit those same emission lines. The broad component of one emission line, known as H-beta, had disappeared entirely, and another, known as H-alpha, had become only weakly visible.

BOSS / Stephanie LaMassa

Spectral lines aside, the object had dimmed to one-tenth its former brightness; once identified as a quasar, the object now looked almost like a galaxy.

So the million-dollar question became: what caused such a drastic and immediate change?

Diet or Dust Cloud?

At face value, the simplest possibility is that a cloud of dust has obscured our line of sight, dimming the quasar’s disk and the clouds of gas that orbit it. But to do this multiple lines of sight must be blocked: our line of sight toward the quasar and the gas clouds’ line of sight toward the accretion disk.

The setup is analogous to the solar system, Gordon Richards (Drexel University) says: even after the Sun has set from Earth’s perspective, it will still light up the Moon and other planets because they have a different line of sight to the Sun. So in this analogy, something would have to obscure both the Earth’s line of sight and the other objects' line of sight to the Sun.

LaMassa and her colleagues modeled how a cloud might obscure a quasar’s spectrum, and they found that no single dust cloud could reproduce the observations. To avoid overly complex scenarios, the research team favors the interpretation that the quasar shut off completely.

But they’re still baffled by how this drastic change could occur in 10 years or less. Astronomically speaking, that’s a blink of an eye. Most accretion disks extend far beyond the orbit of Uranus and emit 10 to 1,000 times more light than their host galaxy. Turning one off seems physically impossible in this short time-frame.

“I’m not sure at what level we would expect the activity to die out at — whether it would be with a bang or with a whimper,” says LaMassa.

This wacky object seems to have raised more questions than it can answer. But AGN expert Paul Martini (The Ohio State University) says it’s a fortunate turn of events. “It’s a great opportunity to study how accretion onto a supermassive black hole shuts down. It’s also a great way to see what the host galaxy looks like right after the end of the quasar phase.”

And if the quasar turns back on, potential abounds. Astronomers think that every galaxy goes through an active stage. “The question is: is it a continuous process?” says Richards. “Is it like a dimmer switch that goes up and down with time but never really shuts off? Or is it like an on-off switch?”

LaMassa observed the object at Palomar only a week after its initial discovery, and her observations in 2014 closely matched the object’s spectrum seen in 2010. Only time (and more observations) will tell if the object will continue to fade into quiescence or return to its initial state. In the meantime, this object has plenty of stories to share.

Reference:

Stephanie M. LaMassa et al. “The Discovery of the First “Changing Look” Quasar: New Insights into the Physics & Phenomenology of AGN”, submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.

6

6

Comments

Navneethc

December 26, 2014 at 12:27 pm

With the 'Dust Cloud' hypothesis, could you explain why there needs to be two sets of such clouds along two different lines of sight? With the Earth-Moon-Sun analogy, the usual moonlight that we see here on Earth can be blocked by nothing more than a 'regular' cloud.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 26, 2014 at 5:44 pm

It seems though that some other observer from some other totally discrete and distant place would need to be blocked from seeing the moon. I think that is the point here. What are the odds that this would happen in the dimensions similar to this in the accretion disk scenario?

JP

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 28, 2014 at 6:21 pm

Nav .. I thought the same thing .. maybe they can see how the Black hole react also? .. or maybe the traveling of the earth to the other side of the prospective every six months? ... or they sent Shannon Hall to the moon??

You must be logged in to post a comment.

robert-simpson

December 26, 2014 at 1:22 pm

I did not see a name or number for the object in the article and the reference link is to a different paper on debris discs around stars. Can you provide the reference?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

December 27, 2014 at 12:18 pm

It's called SDSS J015957.64+003310.5, or J0159+0033 for short.

The reference is provided under "Reference:"

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 28, 2014 at 6:17 pm

dear Shannon! my best compliments for being so young and so bright with a fantastic article!!

I wish you were my daughter!

On regard to the aim of the reporting, assuming that it is impossible that we were so lucky to be present into a switch on/off, I am more for something "crashing" in the middle (even if it looks like they kinda have it under control!!) or maybe the only thing that can give such a power of changes it is the Black Hole close to it ..

How a BH is revolving around the Quasar (or the contrary)?

can it be that it it went scratching the line of sight and absorbing the whole flux of photons?

IF I am am right, please change that stupid long name in Marino's Black Hole! In west LA they would go crazy for me!!

cheers

m

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.