NASA has selected its next New Frontiers mission: Dragonfly, a rover-sized drone will begin ‘coptering around Titan in 2034.

Johns Hopkins APL

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, has long tantalized us from afar. An opaque atmosphere enshrouds a freezing-cold world where methane cycles through clouds, precipitation, and rivers and lakes in the same way that water does on Earth. This environment holds all the ingredients for life — water, organic molecules, and energy — that were present on early Earth.

Now, NASA has announced that its next New Frontiers mission, led by Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle (Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory), will let us see this exotic world as we’ve never done before.

A Dragonfly on Titan

Dragonfly, an eight-rotor, Curiosity-size drone, will launch in 2026 for an eight-year trajectory through the solar system before landing on Titan’s sand dunes in 2034. From there, Dragonfly will conduct dozens of reconnaissance flights, first investigating the organics-based grains that make up the dunes, then flying farther afield to approach and enter Selk Crater. The long-ago impact that created this 80-kilometer (50-mile) wide crater melted water ice, which mixed with organic molecules. NASA’s Cassini probe has already surveyed this region and identified several outcrops where this water-organics mixture exists right on the surface — ideal sites for investigating prebiotic chemistry and even searching for signs of life.

ESA / NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona

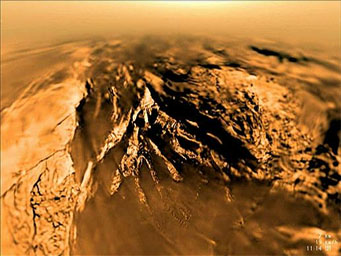

Dragonfly will land exactly one Titan year (29.5 Earth years) after the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe descended through the moon’s murky atmosphere. Huygens was designed as a first look and lasted only 2½ hours on limited battery power. But the glimpse it provided showed us a world that’s strangely familiar despite a surface temperature that hovers around -180°C (-290°F). From above, Huygens saw river-like channels that appeared to empty into a larger sea; the landing site itself resembled a dried up river- or lakebed, strewn with 10- to 15-cm cobbles.

Given this brief look, scientists are itching to investigate this terrain. But they won’t be going to the rivers and lakes. Dragonfly will land, as Huygens did, during northern winter, when the north pole of Titan receives no sunlight. More importantly for communication purposes, the northern, lake-filled regions won’t have a direct sightline to Earth. Without Cassini in orbit to relay communications, Dragonfly will need to transmit data directly.

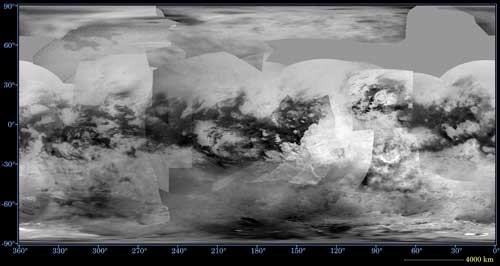

Instead, Dragonfly will travel to the “Shangri-La” dune fields in Titan’s equatorial region, which appear similar to the Namib dunes in southern Africa. While Cassini’s radar could investigate seas and lakes, the probe had more limited capabilities for the sand dunes. “The big outstanding question is the nature of solid surface materials,” Turtle explains. “They hold the keys to understanding the prebiotic chemistry that’s abundant on the surface of Titan.”

Dragonfly’s “Eyes”

For its investigations, Dragonfly will contain many of the instruments that Curiosity carries on Mars. But because the probe will fly instead of roll, it has the potential to cover far more ground than a rover would — more than 175 kilometers (108 miles) over a baseline mission of 2.7 years. That’s nearly double the distance traveled to date by all the Mars rovers combined.

NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

Here’s a brief rundown of Dragonfly’s instruments:

- Downward-looking cameras will investigate the drone’s groundtrack, while forward-looking cameras will investigate the horizon.

- A mass spectrometer similar to the one on Curiosity will drill into the ground, liberating particles that it will then vacuum up into a chamber. It will take measurements, then bake the particles and investigate the gases released with a gas chromatograph

- A neutron-activated gamma-ray spectrometer will investigate bulk surface composition. Usually these kinds of spectrometers rely on cosmic rays to generate neutrons, but Titan’s atmosphere is too thick for cosmic rays to get through. Instead, this spectrometer will generate its own neutrons, sending a pulse into the ground and then investigating the results.

- Meteorology sensors will measure wind and other atmospheric and surface conditions

- A seismometer will sense Titanquakes and use them to investigate the moon’s internal structure

“We’re doing innovation, not invention,” says Turtle, noting that many of these instruments have versions already sitting on the surface of Mars.

Getting Around

Titan’s distance from Earth and the ensuing time delays in communicating with Dragonfly mean that flight has to be largely autonomous. The moon’s atmosphere is four times denser than Earth’s air, while its gravity is seven times weaker, so flight itself is relatively easy. “If you put on wings, you’d be able to fly on Titan,” says NASA Program Scientist Curt Neibur. Likewise, self-flying drones are already commonplace on Earth, so it’s just a matter of applying the techniques to another world.

Johns Hopkins APL

Titan’s atmosphere is opaque, letting little sunlight through, so for power Dragonfly will carry a multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG). An MMRTG is particularly useful on Titan as it dispenses heat along with power. However, the MMRTG produces too low a wattage for high-energy activities like flight, so it will charge a battery to provide power for those purposes. Charging will occur during Titan’s night, which lasts eight Earth days.

Titan’s surface might be tricky; Huygens slid a bit when it landed. So Dragonfly will land on skids. It will also perform “leapfrog flights” to scout out future landing sites. Its first landing site is already chosen, so from there it will scout out landing site B, and then site C, before returning to site B to land. The flights will gradually lengthen to about 8 kilometers (5 miles) in length.

As it soars above the dunes, Dragonfly will be taking images of its surroundings. Given the moon’s similarity to our planet, the views will look a lot like an orange-hued Earth. But there will be some differences: more obvious craters, for one, and a different kind of geography too. “The topography on Titan is fairly subdued in general compared to what we’re used to on a silicate planet, only a mile or so high at most, and the dunes themselves are fairly low,” Turtle explains.

Just as Titan is easier to fly over, it’s also easier to land on. Remember the “seven minutes of terror” experienced by Mars explorers? On Titan, that’s going to stretch to a couple hours. The moon’s low gravity mean that its atmosphere is extended, and entry begins up at 1,100 km. From there, it will open its main parachute at 4 km, then discard that and open a second at 1 km. (It needs two parachutes because with just the main chute, the descent would take even longer.) Then, because Dragonfly can indeed fly, it will disconnect from its protective shell and helicopter to its landing site. You can watch an animation of the landing sequence here:

Good things come to those who wait — exciting times are ahead in 2034!

Do you want to know more about the mission? Ask all your questions next Monday: NASA is hosting an “Ask Me Anything” session on Reddit on July 1st at 3 p.m. EDT.

8

8

Comments

Robert-Casey

June 28, 2019 at 2:55 pm

I expect it will be a challenge to build this probe to operate in the very cold Titan atmosphere. Having the electronics and batteries not mind this very cold environment. Especially when drilling, you don't want the drill to melt the ground and get the probe stuck.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Uwq_1rRhIcDO

June 28, 2019 at 5:58 pm

The first sentence of the second to last paragraph "As it flies, Titan will be taking images of ..." should probably refer to Dragonfly instead of Titan.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica YoungPost Author

June 30, 2019 at 8:48 pm

Yes indeed! I've fixed the typo.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

JasonJ

July 1, 2019 at 5:34 pm

I suppose it's all flying, technically. Some objects are just bigger.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mxyzptlk

June 29, 2019 at 9:17 am

I'm ecstatic the Dragonfly concept was chosen. This is the best news I've heard since Grant took Richmond ! Titan is infinitely more interesting than the dead world of Mars.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

JasonJ

July 1, 2019 at 5:33 pm

First law passed by the people of Titan:

Drone operators must obtain permission from the TAA prior to flying within 400 atmospheres of Titan

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jim-Gasser

July 2, 2019 at 12:32 pm

Any basic idea on how navigation will work? What is the frame of reference? I guess it’s been done many times for various landings but I’m not familiar with it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dobsonite

July 5, 2019 at 6:28 pm

Admirable! "....Curiosity-size drone, will launch in 2026 for an eight-year trajectory through the solar system before landing on Titan’s sand dunes in 2034." That's eight years!

Well, I probably won't BE here for 2036.....but it raises the question: Is there some way we can get our space program moving faster with some of the new propulsion systems we keep hearing about??

Being already ancient, I can remember sci-fi authors of the 50's and 60's already having us on the Moon permanently by 1974...and anyone remember Clarke's 2001?

Oh, and I still can remember a pamphlet put out by General Atomic in 1978 in which they said they expected to "have fully functional fusion plants in place by the year 2000." I think they burned those...

Point being, none of these authors/futurists foresaw the recessions of 1973-74, which sucked up all the lift out of the space program, not to mention the other recessions, the cratering of 2008+, etc....

To quote Yogi Berra, "The future ain't what it used to be!" 🙂

Yogi, it never is. ("Hey, where's my flying car??")

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.