Two studies of star formation in distant galaxy clusters point to different mechanisms of slowing the stellar baby boom that reigned in the early universe.

The star-formation history of the universe still isn’t a settled issue in astronomy. In theory starbirth peaked around 10 billion years ago, and it’s been decreasing ever since, but that’s not an easy thing to verify observationally. Two new studies take a closer look at star-forming galaxies in distant, long-ago clusters — although they raise more questions than they answer.

What Halts Star Formation in Galaxy Clusters?

NASA / ESA / CXC

Galaxy clusters are some of the largest known gravitationally bound structures in the universe. They consist of hundreds to thousands of galaxies permeated by hot gas and dark matter. As galaxies move through their cluster, the denser gas between galaxies is thought to strip away the sparser molecular gas within galaxies, removing their fuel for star formation and decreasing star formation rates. Conversely, galaxies in “the field,” away from clusters, usually have higher star formations rates, since they don’t have outside forces working to remove their fuel.

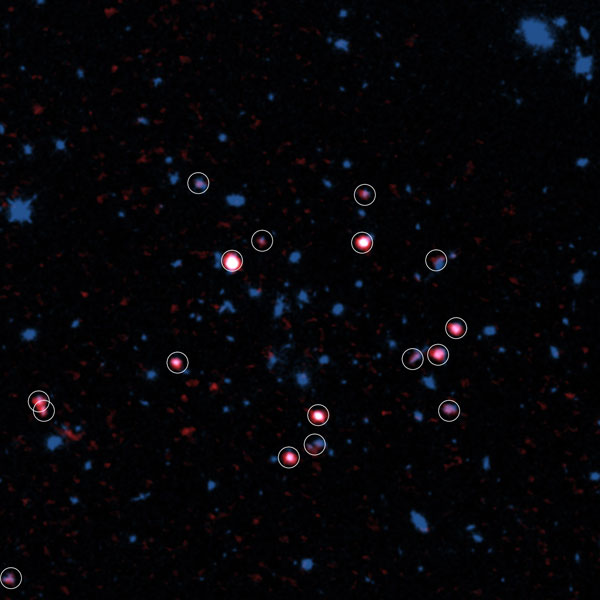

A recent study published in the June 1st Astrophysical Journal Letters appears to confirm this picture. Masao Hayashi (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan) and colleagues used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to observe a galaxy cluster 4.4 billion years after the Big Bang. The ALMA observations pinpointed molecular gas clouds associated with 17 gas-rich and star-forming galaxies in the cluster.

ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO) / Hayashi et al. / NASA/ESA Hubble

All but a few of the galaxies are located in the far outskirts of the cluster, possibly because they’re relatively “new” to the cluster environment, so they haven’t been drawn in close enough to have their gas reservoirs stripped away yet. Presumably, once they fall farther towards the center of the cluster, they’ll lose this fuel and star-formation will grind to a halt.

A Puzzling Result

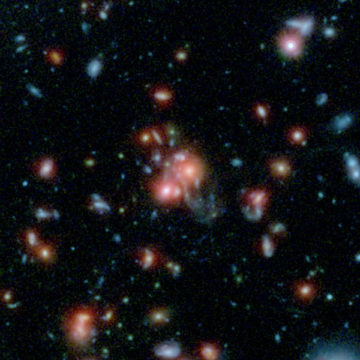

However, astronomers working with the Spitzer Adaptation of the Red-sequence Cluster Survey (SpARCS) have found a puzzling result: in three galaxy clusters that existed when the universe was just 4 billion years old, galaxies have actually had more star-forming material than comparable galaxies in the field. The result is published in the June 20th Astrophysical Journal.

NASA / ESA / JPL-Caltech

SpARCS is the largest survey to date of galaxy clusters that existed in our universe when it was younger than half its current age. Allison Noble (MIT) and colleagues followed up on three of these clusters, again using ALMA to detect the cold gas that fuels star formation. The clusters are some of the most massive known at this distance. Noble’s team found molecular gas clouds associated with seven galaxies and two galaxy pairs across the three clusters.

The researchers compared each galaxy’s cold gas reservoir to its expected rate of star-formation, estimated based on its total mass. Surprisingly, these galaxies contained an abundance of gas compared to the stars they were forming, and even more so when compared to galaxies in the field.

So, how did these cluster galaxies come by their excess fuel, and why don’t they use it to form stars? The authors speculate that something about the cluster environment might prevent some fraction of the gas from feeding star formation. Alternatively, some still-unknown aspect of clusters could account for the different star formations rates in cluster galaxies compared to galaxies in the field.

“While the current study does not answer the question of which physical process is primarily responsible for causing the higher amounts of molecular gas, it provides the most accurate measurement yet of how much molecular gas exists in galaxies in clusters in the early universe,” says SpARCS collaboration lead Gillian Wilson (University of California, Riverside).

Neither study provides any conclusive answers, but they both make new and interesting contributions to what we know about the fuel available for star-formation in clusters at this point in time. As Hayashi states: “The distribution of gas is key to understanding the evolution of galaxies.”

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.