Ten years ago the Spanish island of La Palma was declared a “Starlight Reserve” to protect its astronomical observatories from light pollution and guarantee a dark sky for everyone. The measures implemented to protect the night seem to have worked.

Jan Hattenbach

What makes the perfect site for a professional astronomical observatory? Many clear nights and a stable atmosphere that ensures good seeing, for sure. A location not too close to the equator but far enough away from Earth’s poles to provide usable nights all year long. Accessibility and good infrastructure. And, perhaps most importantly: a population dedicated to protecting its dark skies from light pollution.

In this respect, La Palma, one of the smaller islands of the Canary Islands archipelago in the Atlantic, is an astronomer’s paradise. Its observatories sit on the island’s highest mountain, the 2,400-meter Roque de los Muchachos, protected by law against air and light pollution since the late 1980s.

In April 2007 members of UNESCO, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), and the Instituto Astrofísico de Canaries (IAC) signed the “Declaration in Defence of the Night Sky and the Right to Starlight”, called the “La Palma Declaration” for short. It proclaims, “An unpolluted night sky should be considered an inalienable right of humankind.”

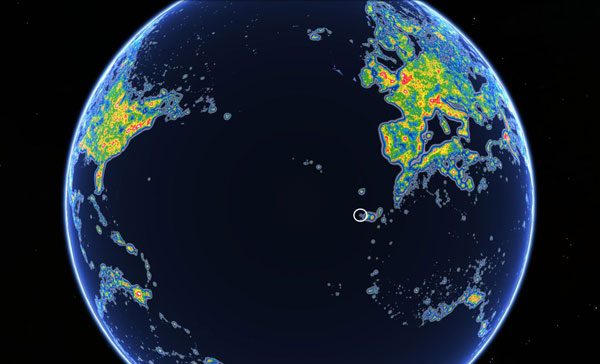

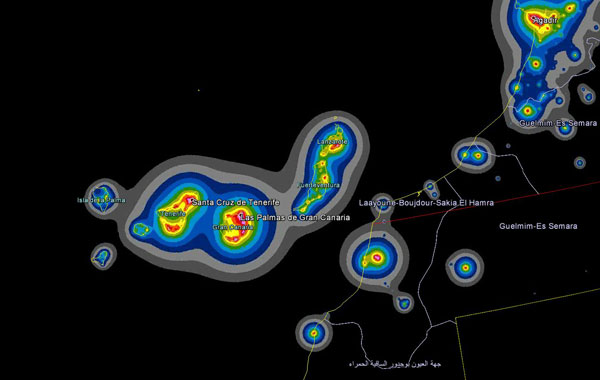

Ten years later I attended a conference held in the island’s capital, Santa Cruz, to commemorate this event, and assess how efforts to preserve the night sky have worked out. A look at the recently released “New World Atlas of Artificial Sky Brightness” (book available online), compiled by Italian researcher Fabio Falchi and others, proves that La Palma’s skies are indeed quite dark compared to the neighboring (and more populated) islands Tenerife and Gran Canaria. Satellite data recorded since the 1990s show that night brightness on La Palma has evolved differently compared to other Canaries and, for that matter, most of the world. Since 2000 nightly illumination has remained stable and the northern regions, where the observatories are located, are still pitch-dark.

Falchi et al. / Sci. Adv. / Jakob Grothe / NPS contractor / Matthew Price / CIRES

Falchi et al. / Sci. Adv. / Jakob Grothe / NPS contractor / Matthew Price / CIRES

The very strict anti-light pollution regulations on La Palma seem to have done the job. All street lights must have an upper light output ratio (ULOR) of 0%, which allows only full-cut-off housings that direct all light to the ground. All ornamental lights have to be switched off at midnight. The regulations also require that streetlights be dimmed by 50% between midnight and dawn. La Palma also specifies maximum levels of light flux, while the rest of Europe limits only minimum levels. The “minimum utilance factor,” which describes the amount of light of a fixture directed to the area that is actually to be illuminated, has to be 50% or more.

Jan Hattenbach

As in the rest of the world, sodium-vapor lamps are being changed out for LEDs, but authorities are planning, as of 2018, to restrict emission with wavelengths below 500 nanometers. Blue light is scattered in the atmosphere and contributes to skyglow more than light at longer wavelengths. So instead of blue-rich white LEDs, La Palma will use phosphor-converted (PC) LEDs, whose amber light resembles the orange glow of the sodium-vapor lamps.

But regulations only work if they are implemented. In northern Chile, for example, similar regulations exist but are not fully enforced. Fortunately, on La Palma, astronomers can count on the continuous support of the local administration and population of the island — this may be the island’s most important advantage.

While astronomy in general, and professional observatories in particular, may have been a bit detached from the island’s everyday life in the past, today’s La Palma is redefining itself as “Stars Island.” The local government strongly promotes the emerging industry of astro-tourism, and the island is a prime destination for amateurs fleeing the oft-clouded and light-polluted skies of the European continent. Even the reluctance of the Instituto Astrofísico de Canaries to welcome visitors has waned: A visitors’ center atop the Roque is nearing completion. The island’s new self-image is perhaps best seen in its network of astronomical viewpoints, areas well-suited to stargazing and outfitted with information placards, scattered over the island.

TMT

La Palma’s hospitality towards astronomers extends to new professional facilities. In March the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) consortium signed an agreement with the IAC to build on the Roque should the original site on Hawai‘i’s Mauna Kea prove infeasible. At the Santa Cruz conference, TMT’s Christophe Dumas explained that both sites are equally excellent with respect to usable nights and seeing conditions, with one important caveat: The Roque is about 2,000 meters lower than Mauna Kea. This lower altitude means more water vapor in the atmosphere above the telescope, which limits observing at near-infrared wavelengths. For this reason, Hawai‘i remains the preferred site for the TMT — but it’s good to know that there’s a backup site waiting with open arms.

1

1

Comments

John-Molineaux

May 9, 2017 at 1:52 pm

Instituto Astrofísico de Canarias

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.