When it comes to planets, there's a fundamental reality: Cratering happens.

Things slam into other things and make holes all the time. Big or small, old or new, simple or complex, impacts are the most ubiquitous geologic features in our solar system. Roughly 1,600 named craters (and countless lesser pits) scar the Moon's ancient surfaces. On Earth, where wind and water continually wear down the land, the census of confirmed impact craters stands at just 176.

Mars, a mixed bag of ancient and modern terrains, lies somewhere in between. Over the years spacecraft have glimpsed ever-finer features in the Martian landscape. These days, the HiRISE camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) can pick out objects only 1 foot (0.3 m) in size; the High Resolution Stereo Camera on the European Space Agency's Mars Express is no slouch either, with a ground resolution of 7 feet (2 m).

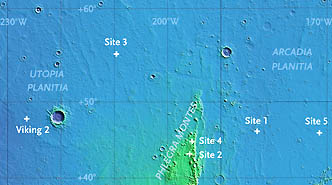

A map of mid-northern plains on Mars shows five sites where craters have excavated ice from a shallow subsurface layer. Click on the map for a larger view.

Data: Shane Byrne; base map: MOLA team

So HiRISE researchers were elated, but not particularly surprised, to discover some small, freshly gouged craters in images taken last year. Seen at five sites over a latitude range of 43° to 56° north, the excavations are typically 10 to 20 feet across and a foot or two deep. How fresh is fresh? One cluster must have appeared sometime between June and August, and a somewhat larger pit showed up between January and September.

What did astound the team were splashes of white seen in and around a handful of these craterlets. Could it be water ice? Colleagues operating the spacecraft's CRISM instrument soon confirmed, for the one case large enough to yield a spectrum, that it was! Apparently fist-size impactors had punched into a layer of ice hidden by a foot-deep topping of dust.

Formed sometime between January and September 2008, this fresh crater has dredged up barely buried water ice and splashed it onto the Martian surface. The HiRISE camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter recorded this false-color close-up on November 1, 2008. The scene is about 100 feet (30 m) across.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona

In the months that followed, these snowy splashes gradually faded from view. Water ice isn't stable at the craters' latitudes, so most likely it gradually sublimated (vaporized) into the atmosphere, leaving behind veneer of any dust that had been mixed with it. The disappearing act might also be due in part to a coating of dust blown in from the atmosphere. Either way, notes HiRISE investigator Shane Byrne (University of Arizona), the icy deposits had to be at least a couple of inches (several centimeters) thick, and they couldn't have been unearthed from more than a foot or two down.

Byrne announced these findings today at a meeting of solar-system specialists in Houston, Texas. He points out that prior surveys, particularly one done by the neutron spectrometer aboard NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter, show that vast reservoirs of ice lay barely buried across most of the planet's polar and mid-latitude regions.

But scientists are only now realizing just how near the surface the ice lies — and how easily it can be reached. When NASA's Phoenix lander dropped onto a northern polar plain last May, its braking engine blew off a few inches of loose dirt and revealed slabs of nearly pure ice.

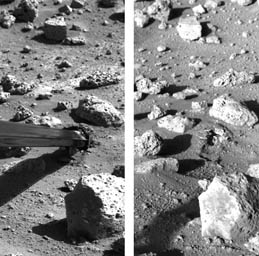

When the Viking 2 lander used its sampling arm to dig a shallow trench in September 1976, mission scientists had no clue that water ice probably lies buried just a foot or two below the surface.

NASA / JPL

The irony in all this is that the Viking 2 lander, which arrived in September 1976, sits just 500 miles (800 km) southeast of the ice-splashed craterlet shown above, and scientists now realize that a layer of water ice almost certainly lies not far beneath its footpads. "It's probably just tens of centimeters down," says HiRISE team leader Alfred McEwen. Had Viking's sampling scoop been able to dig a little deeper, he adds, "we might have sampled ice on Mars 30 years ago."

Beside a robotic arm, each of the twin Viking landers also carried a miniaturized biological testing laboratory — they're the only spacecraft to test for life on Mars before or since. Imagine how much farther along we'd be in our search for past or present Martian microbes if Viking 2 had been able to scoop up some of that ice and test it. And imagine if the mission's twin orbiters had used neutron spectrometers to search for landing sites oozing with buried ice instead of infrared spectrometers to detect water vapor in the thin Martian air.

My guess: astronauts would be making footprints in the Martian dust by now — instead of endlessly circling around Earth in the International Space Station.

2

2

Comments

Rod

March 28, 2009 at 9:01 am

I see the word âimagineâ used twice in this report. Concerning the origin of Martian microbes, how could this happen? Consider the complexity of the genetic code and cell engine in microorganisms compared to rock, dust, and ice on Mars. Do such chemicals spontaneously evolve into the complex genetic code and cell engines of microorganisms given enough time?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rebecca

April 6, 2009 at 2:19 am

Rod, trying to figure that out what science is all about. Hopefully you've not missed the point of the article and the exploration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.