Have you ever spent hours assembling some complicated gizmo and then anxiously hoped it would work when you turned it on for the first time? Boy, I sure have.

So imagine what must have been going through the minds of the European Space Agency's scientists and engineers a few weeks ago as they recorded the first swaths of sky with their shiny new Planck spacecraft.

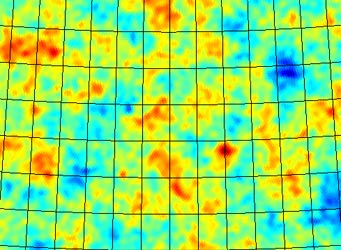

A 10°-wide swatch of sky from Planck's first-light survey reveals minute temperature fluctuations, differences of only millionths of a degree, in the Cosmic Microwave Background.

ESA / LFI & HFI Consortia

Launched on May 14th (together with an infrared observatory called Herschel), Planck is designed to map feeble microwave emissions over the entire sky. This cosmic microwave background, or CMB, is the relic radiation from the Big Bang — think of it as the afterglow of a dying campfire — and its subtle details can teach us much about how the universe began.

Planck is now situated about 1 million miles (1½ million km) from Earth, opposite the Sun, at a gravitational balance point known as L2. From there it will scan the entire sky at multiple wavelengths for at least the next 15 months.

This isn't the first spacecraft to map the CMB — the Soviet Union's Prognoz 9 spacecraft took measurements in 1983, and NASA followed with two hugely successful missions: the Cosmic Background Explorer and the still-kicking Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, which established our current "era of precision cosmology."

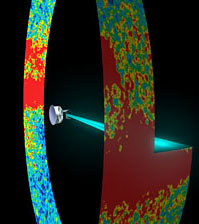

Planck will scan the entire sky to build the most accurate map ever of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the relic radiation from the Big Bang. Planck will take about 6 months to complete a full scan of the sky, charting two maps during its 15 month-lifetime.

ESA / C. Carreau

Planck will extend this work. To record the minuscule temperature variations present in the CMB, the spacecraft's must be cryogenically cooled to near absolute zero (-460°F or -273°C). The resulting maps should reveal details down to 10 arcminutes (one-third the full Moon's diameter), and the wide frequency coverage will allow astronomers to disentangle foreground radiation from galactic and extragalactic sources from the primordial background signal.

So far, everything is working well. The Planck team has just released the spacecraft's first swaths of survey data, representing two weeks of data collected last month at nine different frequencies. Now Planck is pressing ahead to finish its first all-sky map in about six months. ESA has a nice video that explains how this mapping is done, and you can learn more about the successful first-light observations here.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.