Caesar's fleet arrived first at the white cliffs of Dover on the southeastern coast of Britain, but he decided this was not a suitable landing spot.

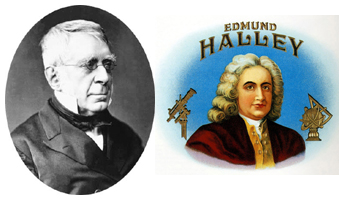

Donald W. Olson

It's not every day that a famous historical event, scrutinized by generations of classical scholars, can be re-dated by two astronomers and their college honors class. But that's exactly what Donald W. Olson and Russell Doescher of Texas State University did, with the help of students Kellie Beicker and Amanda Gregory. They report their findings in the August 2008 Sky & Telescope, which has just hit the newsstands.

Tipped off by Don in advance, I was fortunate to be able to join the team's research trip to the southern coast of England last summer. The white cliffs of Dover, subject of a memorable song from World War II (listen), were also the setting for a much earlier clash of civilizations. Along this very shore, Julius Caesar first landed with two legions of Roman soldiers in 55 BC.

Javelin-wielding Celtic warriors line the tops of the white cliffs to oppose Caesar's initial landing attempt.

Collection of Donald Olson

Caesar, in his first-hand account of the invasion, carefully noted the phase of the Moon, the approach of the equinox, and above all the unexpected ocean tides his fleet encountered. So it's a simple matter for any astronomer to determine the precise date of the invasion, right?

Wrong! No lesser astronomers than Edmond Halley and George B. Airy carefully studied the astronomical aspects of 55 BC in hopes of letting historians know the exact date and location where Caesar and his legions came ashore. But Airy and Halley disagreed with each other. And what's more, they both got it partly wrong, as Olson's Texas State team found out on their research trip.

After moving about seven miles northeastward from Dover, Caesar chose the flat beach between the present-day towns of Deal and Walmer for his landing. But the native Britons had kept pace with the ships, and they were waiting.

Collection of Donald Olson

Some years back, Don realized that the summer of 2007 offered a unique chance to settle this tricky problem once and for all. In 55 BC the full Moon came about three days before lunar perigee and about 3.5 weeks before the equinox, just as in 2007, so the key tidal factors would be virtually identical. On less than a dozen dates in the last 2,061 years has this match been so good. August 2007 offered the perfect chance to find out just where and when Caesar came ashore in 55 BC.

What Needed to Be Determined

There were two top uncertainties to answer about the ocean currents when the Roman fleet arrived off the white cliffs of Dover:

(1) Which way was the current flowing on the traditionally accepted invasion date on the afternoon of August 26 or 27, 55 BC?

(2) Which way was the current flowing on an invasion date four days earlier, one that the Texas State researchers had already started to focus on?

Tides in the English Channel are notoriously difficult to predict, but astronomers George B. Airy (left) and Edmond Halley before him both weighed in on the debate over where Caesar came ashore.

Collection of Donald Olson

To address the first question, our group went to the coastal town of Deal, the area historians have long believed to be the Roman fleet's eventual landing spot because it's roughly seven miles north of the stretch of white cliffs Caesar says he first encountered. That beach is indeed "open and flat," just as Caesar described. I noticed it wasn't sandy at all, being thickly paved with golf-ball-size pebbles its entire length, and wouldn't have been an easy place for Roman warriors to scramble ashore as they dodged a hail of spears and arrows from Britain's hostile Celtic tribes.

Don Olson tosses an apple off the end of the Deal pier to measure the direction and rate of the ocean current.

S&T: Roger Sinnott

On the date in 2007 that corresponded closely to August 26 or 27, 55 BC, we walked out to the end of the Deal pier, which sticks out hundreds of feet into the English Channel. There Don tossed an apple into the ocean at roughly the same time of afternoon Caesar described the movement of the fleet. Sure enough, the apple drifted southwest toward Dover. No way could an invasion fleet, arriving in oar-powered triremes and other ancient warships, have come up from Dover on that particular afternoon.

To address the second question (the current's direction on the revised invasion date, August 22 or 23), we chartered a sightseeing boat that normally takes tourists around the Dover inner harbor. The skipper agreed to take us well beyond the breakwater, into the open Channel and northward along the white cliffs. To view my not-quite-ready-for-YouTube video clip as we pulled away from the Dover dock, click here (QuickTime player required).

Russell Doescher, Kellie Beicker, and Don Olson survey the cliffs from the freely drifitng boat.

Marilynn Olson

Once we were out in the open sea, the skipper turned off the boat's engine. Kellie and Mandy began noting GPS readings and times, crucial data for determining the current's rate and direction by the drift of our boat. And yes — we were drifting northeast toward Deal. So on that afternoon, with lunar conditions so nearly matching those of 55 BC, the Roman fleet would have had no trouble making its way along the coast toward Deal.

I don't know about the others in our group, but I was starting to feel a little queasy as our small boat bobbed around in the choppy seas. I was glad when we got back ashore at Dover. The Roman fleet, its mission only just begun, had no such option.

For more more about the Texas State researchers' findings, check their press release as well as the August Sky & Telescope.

So You Never Knew All This About Caesar?

Time was when all high-school students translated Caesar's Commentary on the Gallic War in second-year Latin class. You know, the famous narrative that begins, "Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres...." The other night I dug out my old textbook. (And Mr. Dalton, if you're out there, I saved a great caricature of you that was surreptitiously drawn by a fellow classmate of mine back in 1961!)

Flipping those old pages to Caesar's Book IV, I saw that I'd underlined the words, "Eadem nocte accidit, ut esset luna plena...," meaning "That night, it happened that there was a full Moon...." Caesar was from the Mediterranean, where there is very little tide, and he didn't know that true ocean tides have nearly their maximum range whenever the Moon is full. As a result, his invasion fleet faced unexpected challenges as they looked for a suitable landing beach on the British shore.

Picking up on subtle astronomical clues like these has been a hallmark of the many projects undertaken by Don Olson and his Texas State researchers for past articles in Sky & Telescope — whether in a well-known painting, the original marathon, or a famous photograph by Ansel Adams.

Located less than 30 miles from mainland Europe, modern Dover is an important seaport. An abundance of harbor lights, designed to help maintain security, has also made this one of the most light-polluted cities on Earth.

Roger Sinnott

The Roman army's historic landing on the coast of Britain in 55 BC involved perhaps 100 ships and 10,000 men. But this was a rather limited incursion, by Caesar's own standards. Buoyed by the sensation his exploits caused back home, Caesar returned to Britain the following spring (54 BC) with an invasion fleet perhaps 10 times larger. It was like a D-day in reverse.

Caesar's crossing of the Channel, nearly 21 centuries ago, would alter the course of British history forever.

6

6

Comments

Gerald Hanner

June 25, 2008 at 1:34 pm

Roger:

In reading you comments of queasiness bobbing around there in the English Channel, I can identify with you. I've beed fishing on the North Sea, a bit farther north than you were; I have hung my head over the side of the boat more than once. The ocean conditions there are rough by any standards almost every day of the year.

I used to listen to the BBC radio sea conditions report most mornings. Many times it was reported as "blowing like Billieo."

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joseph Slomka

June 27, 2008 at 11:50 am

Ah!

I remember fondly reading Caesar's Gallic Wars, also Cicero's Oration

against Cataline, and the Aenid!

I consider myself the last of the liberal arts majors, amid a swam of

geeks and engineers. I also read New Testament Greek.

Oh, for the good old days!

Clear Skies

Joe Slomka

Albany Area Amateur Astronomers

You must be logged in to post a comment.

C.L. Mullins

June 28, 2008 at 7:46 pm

I am dedicated to the "hobby" of astronomy and appreciate articles that help me in my quest for more information and knowledge about the sky above. But for the life of me I fail to see the importance of the landing of Caesar in England. I am also a retired teacher OF HISTORY but that doesn't change my thougths about the article and why it was in your publication.

Please in the future publish MORE things that pertain to the "hobby" of astromony.

Thanks,

C.L.Mullins

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Geoffrey West

July 2, 2008 at 4:25 am

A number of questions arise from reading this article! What was the sea level at that time, how wide was the English Channel, how does the bathymetry of the offshore waters then compare to the present day, was the tidal regime the same then, is it correct to assume that the direction and strength of the offshore/longshore currents were the same, at what rate have the cliffs eroded since then, etc?

In other words, what is the point of floating apples or boats off the present shore line when the shore in Roman times must have been so different?

A modern cross section shows that a drop in sea level of about 30m would result in a shoreline some 8km further out than at present, with the width of the channel reduced from 38 to 20km!

If only we had a palaeogeographical reconstruction!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Elena

July 3, 2008 at 2:43 am

I happen to be reading at present Oxford's History of Britain, book 1, Roman Britain, so this article comes rather timely. I am Italian and as such at school I went through several readings of the Gallic Wars, rigorously in Latin, and later on in life I went back to them with relish, Gaius Julius Caesar was a brilliant commentator of other peoples and customs, with a keen eye for geography and local conditions (although a bit biased, like most Romans of the time).

It may not change someone's life to know with a bit more certainty when Ceaser landed in Britain, we can certainly sleep without this knowldege, but so can we with everything else in life apart from the most immediate survival needs. It is part of the human spirit to be curious and to seek answers. It is also part of the scientific method to seek independent proof of one's theories, and in this case the astronomers gave proof to historians conjectures based on different data. It is in my opinion a good example of two very different sciences helping each other towards scientific proof of an event. AND the event certainly had momentous and lasting consequences for Britain itself!!!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Howard

July 9, 2008 at 11:03 am

I agree with Elena. This was a nice synthesis of multidisciplinary data, some of which was certainly astronomical. A mix of amateur and professional work and it dealt with a famous historical event. I certainly learned a bit more basic astronomy and history, what more can you ask for?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.