The upcoming total solar eclipse is understandably getting a lot of attention, but don't overlook the trusty Perseids. They'll be getting things warmed up Saturday night.

What? There's a meteor shower? Oh yeah, the Perseids! If anything's been eclipsed this month, it might be this reliable, annual shower expected to peak Saturday night–Sunday morning, August 12–13.

Although the Perseids have taken a back seat in recent years to the more numerous Geminids of December, it remains the best known meteor event of the year. With up to 80 vaporizing comet granules visible per hour from a dark sky and pleasant weather to boot, meteor watching doesn't get much easier.

That's assuming the Moon doesn't throw a bucket of cold light on the scene. And it won't until around 11:00 p.m. local time Saturday, when the 70% waning gibbous rises in Pisces. That means reasonably dark skies until at least 11:30 p.m. for a good evening show. Meteors will spitball from a point 5° east of the Double Cluster, some two fists high in the northeastern sky. Numbers will peak toward 4 a.m. on the 13th, but the Moon will shine high in the southern sky then, rendering the fainter shower members invisible and reducing counts to 20–30 per hour. That may be low for the Perseids, but well above the I-don't-feel-like-getting-up threshold.

See the Earth pass through the 109P/Swift-Tuttle's stream of debris in this interactive visualization. Click and drag to turn. Right-click to pan. Scroll to zoom.

Peter Jenniskens and Ian Webster

Perseids originate from material boiled off the nucleus of comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. In its yearly run around the Sun, Earth bumps into the first bits of 109P's dust and ice around July 17th and exits the stream around September 1st. We're right in the thick of it in mid-August, when for several nights flaming meteoroids get the attention of even the most casual skywatchers.

Zoran Novak

Lots of people head out to their hammocks or sprawl out on a sandy beach or grassy lawn, talk quietly, check their phones, and share a few laughs to the shower's paired rhythms — spells of sweet languor punctuated by sudden bursts of meteoric excitement. I like a reclining lawn chair, a warm coat, and camera at my side just waiting for that jaw-dropping javelin of light.

Perseids enter the atmosphere on parallel paths, which is the reason they appear to radiate from one spot in the sky and a sure way to tell them apart from sporadic or non-shower meteors. Follow a suspected Perseid path backwards and it will point to Perseus. Looking toward the radiant is the same as looking down a set of train tracks. The tracks are parallel but appear to converge in the distance due to our perception. Things farther away look smaller, so the parallel rails of a railroad track appear to get closer together as you look farther away. Same with the Perseids!

Bob King

As Earth tears through the stream of debris, Perseids slam the atmosphere at speeds of 59 km/sec (133,000 mph), become heated by friction, and vaporize to fine dust. The incoming grains heat and compress the surrounding air, causing the air molecules to lose electrons and become ionized. These "ionization trails" make excellent reflectors of radio energy; hams use them as temporary reflecting "surfaces" to bounce signals all around the globe.

When the molecules snatch back their electrons, they release energy as a luminous streak — the meteor — as well as the occasional longer-lasting, smoke-like "train." Perseids have frequent trains that resemble chalk marks drawn against the sky that disappear in a second or two.

Like fishermen, we'll all be waiting for meteors to bite Saturday night. Whichever direction you choose to face, avoid looking at the Moon to preserve whatever night vision you can. If you plan to take photos, keep the Moon out of the frame.

Capturing the View

Alexander Vasenin

Meteor photography is best with a wide-angle lens (17mm–35mm) set to its widest aperture (f/2.8-4). Click the lens from auto (A) to manual (M) and focus at infinity by pointing the camera at a bright star. Select the live view feature that lets you see a preview of the photo you're about to take on the back LCD screen. Change the ISO to 800 and exposure time to 30 seconds, then click away. You're best off using an intervalometer (available on eBay and Amazon for many makes and models) that does the picture-taking for you, while you kick back, sip coffee, and relish the night scene.

If poor weather prevents you from watching the Perseids, Italian astrophysicist Gianluca Masi will be at your service, live-streaming the shower starting at 3 p.m. CDT (20:00 UT).

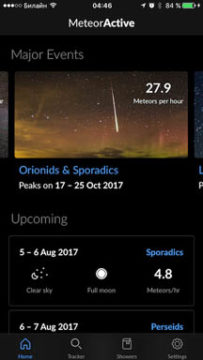

And just this month, Russian software developer Alexander Vasenin released his free MeteorActive app (iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch only) that includes detailed meteor activity forecasts of major and minor showers now and in the future. It makes a great planning tool. I like that he includes sporadics and other meteor types in the total number of meteors one might see when watching a meteor shower.

Enjoy the calm and solitude of the Perseids before you have to jockey with the madding crowd for a spot under the moon's shadow only a week later.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.