What is the "autumnal equinox" — and how do we know when it happens?

If you've gotten your coat out of the closet, closed your windows at night, and felt that telltale crispness in the air, it seems like autumn has already begun. Astronomically speaking, however, fall comes to the Northern Hemisphere this year on Thursday, September 22nd, at 14:21 Universal Time (GMT). That's 10:21 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time.

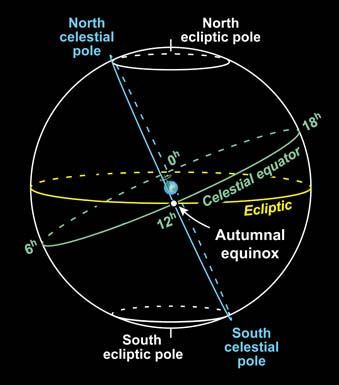

Why? This is the moment when the Sun crosses precisely over Earth’s equator as it heads south for the season. Or to put it another way, it's when the Sun crosses the celestial equator as astronomers define coordinates on the sky: declination 0°. For us northerners, this is called the autumnal equinox.

Timing the start of fall to 1-minute precision may seem pretty obsessive for seasons that, around us on Earth, gradually flow from one to the next. But from a celestial standpoint, such precision naturally falls out of the wheeling of our tilted planet around the Sun.

Sky & Telescope illustration

If you were watching the scene from far away in space, you'd see Earth's Northern Hemisphere tipped sunward during its hot months, and tipped away from the Sun a half year later when Earth is on the opposite side of its orbit: winter. The spring and fall equinoxes are the instants halfway between, when the Sun shines equally on both hemispheres.

From our own point of view here on the ground, we see the Sun follow an arc across the sky each day, from east to west, as Earth turns. During the months when the Sun is north of the equator, its daily route takes longer and it's higher in the sky for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. That's why summer is hot, and why the Sun of June and July passes so high at midday.

In December and January we see the Sun's daily arc at its shortest and lowest, which is why winter is cold.

The same sequence happens in reverse for the Southern Hemisphere. There, the September equinox marks the beginning of spring. Christmas in Australia is a hot summer holiday for the beach, and July is when you shovel snow.

And if you live on Earth's equator? There the traditional seasons don't really happen; people think more in terms of local cycles like “wet” and “dry.”

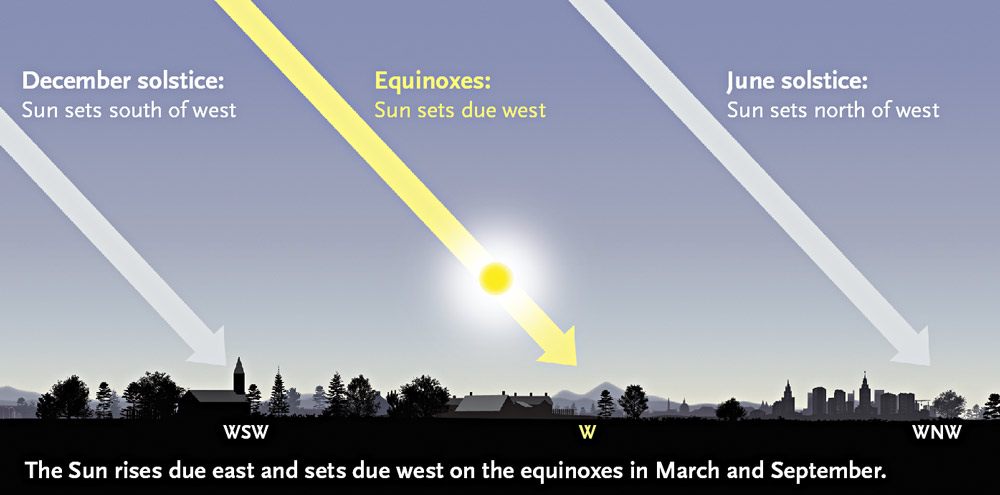

Sky & Telescope illustration

Several other noteworthy situations occur on the equinoxes:

- Day and night are nearly the same length; the word “equinox” comes from the Latin aequinoctium, meaning “equal night” (says the Oxford English Dictionary). That's if you define "night" as starting right at sunset and ending at sunrise, rather than as the period of complete darkness. However, your almanac will show that sunrise and sunset on Thursday are not precisely 12 hours apart. This is for two reasons. First, "sunrise" and "sunset" are defined as when the Sun’s top edge — not its center — crosses the horizon. Second, Earth’s thick atmosphere at the horizon refracts the Sun’s apparent position upward by about ½° around sunrise and sunset. The “equal night” business would be truly correct only if the Sun were a point rather than a disk, and if Earth had no atmosphere.

- On this day the Sun rises due east and sets due west (for anywhere on Earth), as shown above. The equinoxes are the only times of the year when this happens (again with a slight fudge factor for the two reasons above).

- It you're standing on the equator, the Sun will pass exactly overhead at midday and you'll cast no shadow. Stand at the North or South Pole, and you'll see the Sun skim completely around the horizon over the course of 24 hours.

2

2

Comments

September 22, 2016 at 8:32 pm

A few years ago, I saw a halo with "sun dogs" (those 2 bright spots that sometime appear in a halo) late one September afternoon. In the late afternoon, the "sun dogs" appear on either side of the sun, and parallel to the horizon. A halo is 22 degrees in diameter - roughly the same angular width as the distance between where the sun appears at the equinox and either solstice point. Since the setting sun was near the autumnal equinox, the "sun dogs" marked the approximate points where the sun would be setting on the Winter and Summer solstices. If anyone is lucky enough the see a rising or setting sun with "sun dogs" nearby in the next week or so (or in six months near the Spring Equinox), be sure take note of the event!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

September 22, 2016 at 8:33 pm

Oops, it should have read, "A halo has a radius of 22 degrees ... "

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.