Visible to backyard observers everywhere, the Great Nebula in Orion is a relatively bright and easily located nebula lit aglow by clutches of newborn stars scattered among its fluorescent gases.

Sky & Telescope photo by Richard Tresch Fienberg.

Welcome to Kosmic Ken's Observing Emporium. You say you need some advice on stargazing? Let me peer into my crystal ball. Ah yes, a picture is emerging . . . .

I see that you're relatively new to backyard astronomy. You own a starter scope and you're getting the hang of using it. You're having fun observing the Moon and planets — and maybe double stars, too. If I'm reading the picture correctly, you also want to go after some tougher targets, such as star clusters. . . a nebula or two. . . maybe even a few galaxies. But you're worried that they might be too faint and fuzzy. This is subtle stuff, they say, and you don't know where to begin.

Well, you've come to the right place! Listen closely . . . .

The things you seek are called deep-sky objects. Simply put, the term refers to all celestial objects outside the solar system. In essence, though, we're talking about star clusters and nebulae within the Milky Way, plus the myriad galaxies beyond. (Individual stars, double stars, and

Three deep-sky categories personified: a globular star cluster (M13 in Hercules), a planetary nebula (the Helix, in Aquarius), and a galaxy (NGC 253 in Sculptor). Each class poses its own challenges and offers its own rewards to the observer using binoculars or a small telescope.

Sean Walker (left) / Lee Coombs (center and right)

constellations, while also outside of the solar system, are a different kettle of fish.) In the lexicon of amateur astronomy, star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies aren't just far — they're "deep."

Yes, most deep-sky objects are a challenge to observe, especially if you're working with modest equipment under a suburban sky. So what makes the little fuzzies so special? In a word, it's their exclusivity. When a faint cluster or nebula materializes in the eyepiece of your telescope, you're scrutinizing a part of the Milky Way that might be several thousand light-years from Earth. Gaze upon a galaxy, and the light-years number in the millions.

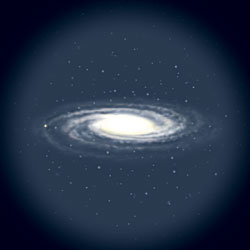

Our Milky Way galaxy, seen from a hypothetical outsider's viewpoint. Open star clusters and emission nebulae typically reside within the curvy spiral arms, while globular clusters pepper the spherical halo surrounding the entire disk. Some 26,000 light-years from our solar system, the central bulge lurks behind dust clouds in Sagittarius.

S&T: Steven Simpson

Galactic Geography

Allow me to put this in perspective with a brief lesson in galactic geography.

Picture our galaxy as a stellar metropolis containing billions of stars. The central hub, or bulge, is congested with mostly older suns. Away from the hub, the galaxy thins into a disk of gas, dust, and stars of all ages. Rippling through the disk like ocean waves, a pinwheel pattern of glowing spiral arms hosts the youngest stars and the nebulae associated with their births. Our middle-aged Sun and its family of planets reside in a suburban neighborhood called the Orion Arm, which is located roughly two-thirds of the distance from the downtown core to the city limits. Finally, in the galactic outskirts, a vast halo dotted with clusters of ancient stars surrounds the whole galaxy.

Viewed from Earth, portions of several spiral arms blend together in our night sky to form the arching band of the Milky Way. Deep-sky treasures abound in and around that glittering band. Click ahead to the next section, and I'll conjure up some examples for you.

Sparkling M35 is a clutch of young stellar siblings at the feet of Castor (immortalized in the constellation Gemini along with his half-brother Pollux). A similarly sized but far more distant cluster, NGC 2158, lies southwest of M35; it looks like a small cloud at lower right here. This photograph, like most in this article, is oriented with celestial north up and east to the left.

Clusters Near and Far

First of all, the Milky Way features not just countless stars but hundreds of eye-catching open clusters. Each open cluster is a gravitationally bound clan of anywhere from several dozen to several hundred stars. These clusters span a wide range of ages, but typically they are no more than a few hundred million years old — mere toddlers compared to our 4.6-billion-year-old adult Sun. Many open clusters are comparatively large and bright. Binoculars are excellent for spotting them against the celestial background.

A splendid example is Messier 35 (M35). Located 2,800 light-years away in the constellation Gemini, M35 contains about 200 suns. In 7×50 binoculars, you might count half a dozen stars sprinkled against a coarsely textured haze spanning nearly a half degree (nearly the apparent size of the full Moon). Viewed through a telescope at low magnification, M35 fills the eyepiece field with curving chains of stars.

Globular clusters are quite different. Our galaxy's halo is dotted with about 150 globulars, each a dense ball of several hundred thousand stars. And get this: their stars are 12 to 13 billion years old, making the globular clusters the senior citizens of the Milky Way.

One of the finest globulars in the northern heavens — and certainly the easiest to track down — is Messier 13 (M13), the Great Cluster in Hercules. Some 21,000 light-years distant, M13 shows up in binoculars as a faint, out-of-focus "star." However, a 6- or 8-inch (150- to 200-mm) telescope used at moderately high magnification (100× or 150×) can resolve the blur into a hive of glowing dots.

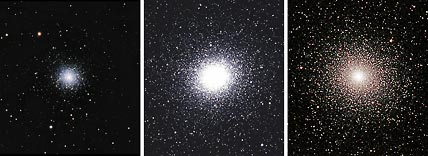

Messier 13, Omega Centauri, and 47 Tucanae personify globular clusters, spheroidal gatherings of ancient stars by the hundreds of thousands. M13, in Hercules, is a perennial favorite for telescope users north of the equator, while Southern Hemisphere observers can enjoy rich views of the other two globulars even with binoculars.

Lef to right: Sean Walker / Akira Fuji / Hermann von Eiff

In the far-southern heavens, two magnificent globulars vie for attention. 47 Tucanae (NGC 104), 16,000 light-years away in the constellation Tucana, is a fuzzy "star" to the bare eye. And though it's slightly farther away, Omega Centauri (NGC 5139 in Centaurus) appears as a larger circular haze that is partly resolvable even in binoculars. In a telescope, this massive chandelier of suns is simply spellbinding. "Omega Cen" is the acknowledged king of globular clusters.

Misty, Mysterious Nebulae

A variety of nebulae can be found throughout the Milky Way, but I'll describe just two main kinds. The first, called an emission nebula, is an immense store of hydrogen gas that has been excited (that is, energized) to incandescence by hot, newborn stars within or near it. Some emission nebulae are the sites of active star formation.

In the middle of Orion's Sword (or scabbard) lies a nebulous jewel, Messier 42 (M42), whose glowing tendrils, dusty indentations, and bright baby stars can be inspected with even a small telescope and even through moderate light pollution. (In the wide-field photo at left, the diagonal row of three bright stars at top is the familiar Orion's Belt.)

Left: Akira Fujii; right: Rick Fienberg

Messier 42 (M42), the Great Orion Nebula, is a superb example of an emission nebula. This celestial nursery, some 1,400 light-years away, cradles a quartet of bright infant suns called the Trapezium. The fan-shaped nebulosity illuminated by the Trapezium is an absorbing subject to study through any telescope. M42 is plainly visible in binoculars and can even be discerned by sharp-eyed people from dark backyards. Moreover, because Orion straddles the celestial equator, the Great Nebula is accessible to amateur astronomers all over the world.

A second type of nebula, called a planetary nebula, represents a brief moment in the last stages of a star's life cycle. A planetary nebula is a shell of gas that has been ejected from a dying star — one that has exhausted its ability to generate energy by nuclear fusion in its core and is destined to fade to near-invisibility. Viewed through a small telescope, a typical specimen offers little more than a blue-green, vaguely planetlike disk — hence the name "planetary."

The castoff mantles of dying stars, planetary nebulae like the Ring Nebula in Lyra (left) and the Helix Nebula in Aquarius (right) can be highlighted slightly by using a so-called 'nebula filter' at your telescope's eyepiece. The Ring, tiny but relatively bright, hardly calls for a filter. But the Helix, large and very faint, shows up much better when one is used.

Left: Rick Fienberg; right: Lee Coombs

Fortunately, the best planetaries have more character. The Ring Nebula, Messier 57 (M57) in the constellation Lyra, is famous for its sharply defined structure. Viewed at high power, the small but conspicuous Ring is a cosmic Cheerio adrift in space 1,400 light-years from Earth. No other deep-sky object visible through amateurs' telescopes looks quite like it.

If your skies are truly dark, you'll also want to chase down NGC 7293, the Helix Nebula in Aquarius. Only 400 light-years distant, the Helix appears about 10 times larger than M57 on the sky, but it is extremely dim. Even so, this ghostly cousin to the Ring will materialize as a misty oval in a good pair of binoculars or a wide-field telescope used at low magnification under a black sky.

Beyond the Milky Way

Now for the really exotic stuff. Beyond the Milky Way are the galaxies. Spot a galaxy and you're peering millions of light-years into the universe at large. Obviously, these incredibly remote targets present a challenge for beginners. Although galaxies come in various classifications, you might consider the distinctions academic because most galaxies appear featureless in small telescopes. But there are exceptions.

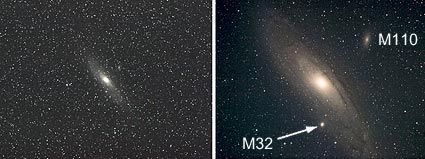

Left: Our nearest neighboring spiral galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, looms nearly overhead late on autumn evenings for observers at midnorthern latitudes. Right: While M31's elliptical bulge (which dominates this photo) is the only component readily seen in binoculars or small telescopes, hints of the galaxy's dust lanes can be seen telescopically under pristine skies, as can M31's two miniature satellite systems, M32 and M110.

Left: Akira Fujii; right: Rick Fienberg

The Andromeda Galaxy is one. Even though it's 2.5 million light-years away, the Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31 (M31), is visible to the unaided eye as a tiny, diffuse cloud on a perfect autumn night. A spiral system like our Milky Way, M31 is inclined somewhat to our line of sight. Under pristine skies, good binoculars will show M31 as an elongated wisp with a bright central condensation (this bright, oval bulge is the only part that readily punches through suburban skyglow). A short-focus, wide-field telescope can frame the whole galaxy in a low-power eyepiece. Bumping up the magnification (again, under very dark skies) might provide hints of spiral arms and of pencil-thin dark lanes — the silhouettes of dust clouds congregating in M31's midplane.

Diversity amongst the disks. Three spiral galaxies displaying disparate forms, thanks to their varied orientations. Left: The Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51 or M51), seen face-on in Canes Venatici, near the Big Dipper's handle. Middle: NGC 4565, seen edge-on in Coma Berenices. Right: NGC 253, seen at an intermediate angle in far-southern Sculptor.

Left: Akira Fujii; center/right: Lee Coombs

Two galaxies in the Northern Hemisphere's springtime sky offer different perspectives. The Whirlpool Galaxy, Messier 51 (M51) in Canes Venatici, is presented fully face-on. Despite being 35 million light-years away, M51's spiral structure is distinct through telescopes as small as 8 inches under dark skies. By contrast, a spiral in Coma Berenices called NGC 4565 appears almost exactly edge-on. About 10 million light-years closer than the Whirlpool, this galaxy's spindly form stretches across a high-power field of view if sky conditions are good.

And a mere 9 million light-years away is NGC 253, a prominent galaxy in the Southern Hemisphere springtime constellation of Sculptor. Aligned not quite edge-on to our view, cigar-shaped NGC 253 displays an uneven, grainy texture in good 4-inch telescopes, and it is a relatively easy catch in binoculars.

M51 stands apart in another way: it's really two galaxies, not one. A smaller body, NGC 5195, orbits the main spiral (you can see it in the photo above, near the tip of one spiral arm). And while M51's spiral structure can be seen at the eyepiece only under relatively dark skies, the system's double nature can be perceived as two tiny, unequal dim blurs even with a small telescope contending with suburban viewing conditions.

Hooked Yet?

Yes, it's true — I see fuzzies in your future. If you're like the other backyard astronomers I know, you'll be drawn to the deep sky — not in spite of its challenging nature, but because of it. You'll find yourself targeting the same objects over and over. Just as you strain to glimpse fine detail on Mars or Jupiter, you'll develop a thirst for your best-ever observation of a particular star cluster, nebula, or galaxy, and soon you'll develop your own list of personal favorite friends to visit again and again through the seasons.

For the fine points of deep-sky observing, plus more about the objects you can see in small telescopes, browse through the How To and Observing sections of this Web site. You'll be hooked in no time.

Oh-oh, now I see trouble. My crystal ball shows you lusting after larger telescopes and better star charts. But don't blame me; I'm just the messenger. Five dollars, please.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.