It's easy to like Jupiter. No other planet offers such a bounty of amazing sights through the telescope, especially this week when it reaches opposition.

Bob King

On April 7th, the largest planet in the solar system will rise at sunset and shine all night. That's the date Jupiter lines up behind the Earth in opposition. The planet's closest approach to Earth follows immediately after, on April 8th. On these two nights, Jupiter appears larger than it has or will on any other night of 2017.

What's more, it's in the company of Virgo's brightest star, Spica. Soon after Jupiter rises, Spica does, too, each complementing the other to make for an arresting sight. Although the apparent distance between the two will increase some, their tryst continues through the summer.

Jupiter's a joy, especially now that Venus has slid into the morning sky and Mars and Mercury will soon be overtaken by dusk. I love wrapping up a night filled with faint fuzzies with a bright planet.

And the big guy never disappoints.

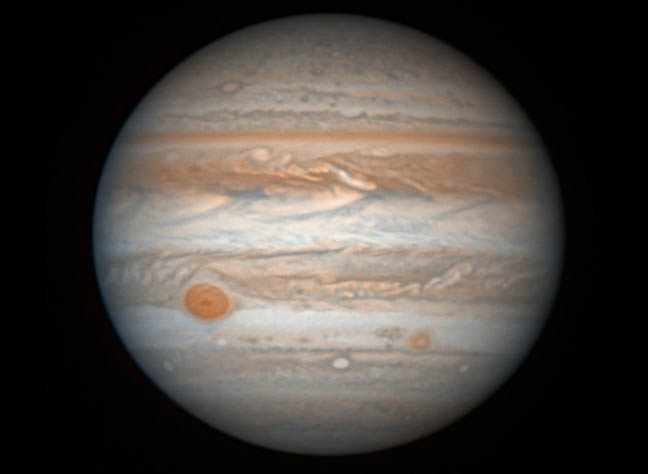

With cloud belts shaped by swiftly shifting weather, oval storms plowing through the cloud tops like migrating salmon, and the ever-changing configurations of its four brightest moons, Jupiter always offers something new on the platter. Want to see a cloud belt disappear? Multiple storms merge into one? Moons cast the most perfectly black, round shadows on wormy clouds of ammonia ice? Regular observation of the planet will show you these and much more.

Damian Peach / Chilescope team

Thanks to Jupiter's rapid rotation of just under 10 hours, you don't have to watch too long to see new features appear at the eastern limb. I can't tell you how many times I've seen the Great Red Spot, a larger-than-Earth hurricane-like storm, peep over the eastern limb, then stayed out another 40 minutes of the planet's rotation to bring it into full view. You feel compelled to find out what's coming round next. Before long, it's 1 a.m.! Jupiter makes the time fly.

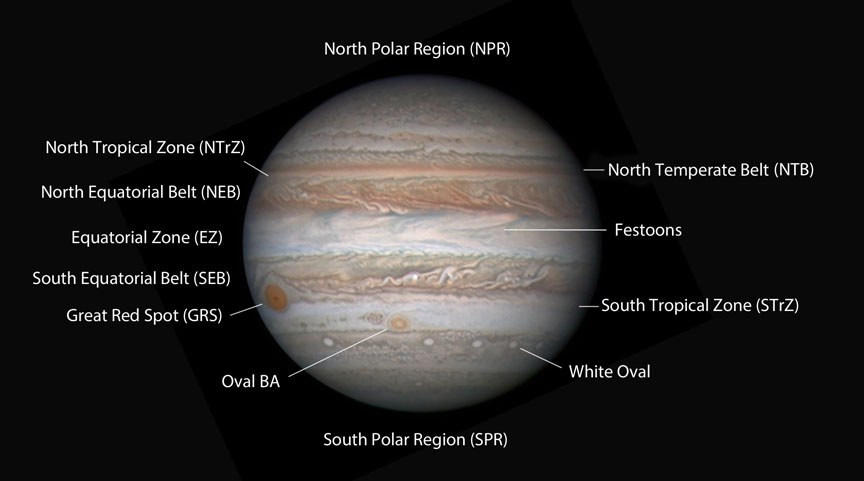

Damian Peach with annotations by the author

Not all oppositions are equal because planets don't orbit in perfect circle, but squashed ones called ellipses instead. One end of the ellipse passes nearest the Sun at a point called perihelion, the other farthest from the Sun at aphelion. Jupiter reached its greatest distance from the Sun on February 17th, just seven weeks before opposition. This makes the April 7th opposition the most remote of the past dozen. Jupiter can shine as brightly as magnitude –2.9 with a disk 50″ across; this time around it will manage –2.3 and 44.2″ diameter. Ah, but what's a few arcseconds when you're having fun?

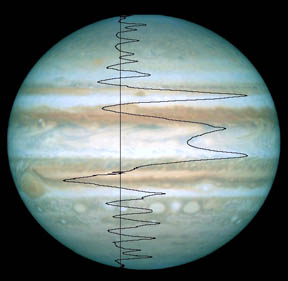

NASA

Easiest to see and visible in almost any telescope are the two "tire tracks" of the North Equatorial Band (NEB) and South Equatorial Band (SEB) along with the bright Equatorial Zone (EZ) that separates them. The bright zones have higher, thicker clouds compared to the ruddy-gray belts that lie deeper in the atmosphere and are overlaid with a thick, smoggy haze.

Additional narrower belts are also visible especially if you increase the magnification to 100× or higher. At that power, the North Tropical Band (NTB) comes into clear view and other more delicate bands, including the South Tropical Band (STB), a thin gray stripe that parallels the SEB just south of the Great Red Spot (GRS).

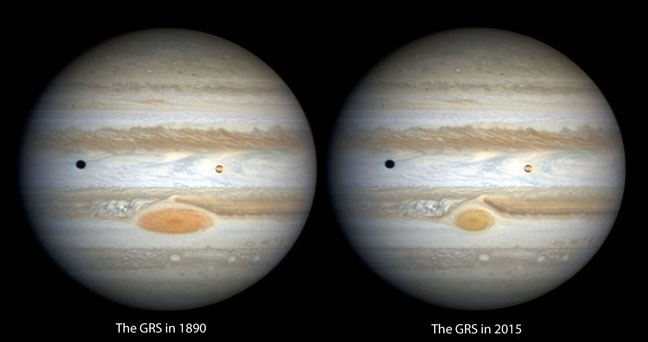

Like any storm, the GRS is subject to change in size and ferocity. Back in the late 1800s, the beast extended for 47,700 km (29,000 miles), 3.6 times the diameter of Earth. By 2016 it had contracted to just 16,500 km (10,250 miles), or 1.3 Earths, and become more circular, too. Will it stabilize, re-bloat, or fade away for good? No one knows.

Happily for spot seekers, the GRS nests in a pale white nook called the Red Spot Hollow, which sets it off from its surroundings. While the GRS can seen at 60×, 100×–150× will provide a clearer view. Like a chameleon, the Spot also changes color. I've seen it peach, orange, tan, pink, and brick-red. Currently, its flush-pink like a child's cheeks after playing outside on a winter day.

Damian Peach

Finer features that require steady seeing and magnifications of 150× or higher include the mini Red Spot nicknamed "Red Spot Jr.," or more formally, Oval BA. This modest spot, about 1/3 the size of the GRS, formed in 2000 when three smaller ovals merged. Also be sure to keep your eye out for the smaller-yet whiter ovals, which are fairly common along the south edge of the Southern Polar Region (SPR) but can appear elsewhere on the planet. Some of these have shown up in recent photos taken by NASA's Juno spacecraft. Reserve them for the best nights.

Christopher Go

Finger-like festoons often streak the EZ and occasionally, smaller belts will show gaps or missing sections. One of the most fascinating features to watch for is the long stream of turbulent clouds east of and in the wake of the GRS. When conditions are right, you'll be astounded by the detail visible.

One caution: don't expect the features you see in pictures to necessarily stick around. Changing weather erases cloud bands, creates new ones, alters spots, and changes the number and shape of the festoons. Jupiter's all atmosphere and clouds, and those are subject to change much like the weather on Earth.

The only thing that changes more than the weather at Jupiter are its moons. Each of the four brightest — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — lies at a different distance from the planet and orbits with a unique period, ranging from 1.7 days for Io to 16.7 days for the more remote Callisto.

Stellarium

Together, they weave the most amazing arrangements and combinations imaginable. Make a regular habit of watching the satellites and you'll see sometimes see all four strung out on one side of the planet like laundry drying on a clothesline. Other times all are missing save one. Or three will gather in a compact triangle on one side of Jupiter with their sibling shining all by itself on the other.

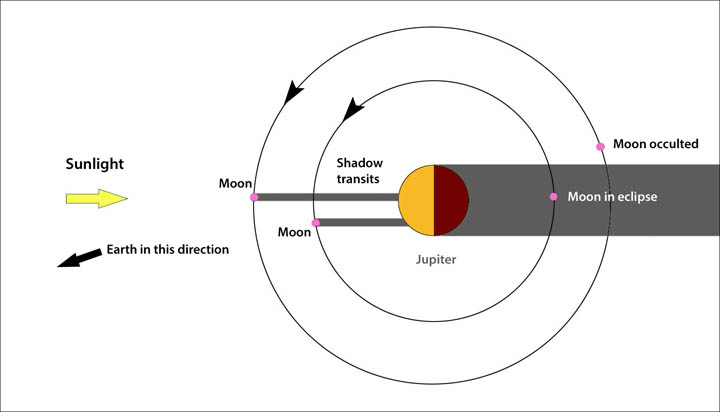

Bob King (after Encyclopedia Britannica)

The moons also cast shadows on Jupiter's cloud tops during events called shadow transits, suffer eclipses by the planet's shadow, and disappear and reappear next to the planet's limb during occultations. Jupiter's got it all. Come see!

** This just in. To take advantage of Jupiter's proximity at opposition, the Hubble Space Telescope just snapped a brand new closeup image of the planet. The new photo will be released on Thursday, April 6 on the Hubblesite. Check it out.

Resources for Jupiter Observers

- Transit Times of Jupiter's Red Spot. Want to see the GRS? Use this handy Sky & Telescope utility to find out when it transits Jupiter's central meridian. Jovian features are well visible for about 2 hours centered on the time of transit.

- Find Jupiter's Moons. This S&T interactive tool will show you which moon is which!

- Phenomena of Jupiter's Satellites. A .pdf file listing the times for every transit, eclipse, and occultation of Jupiter's four brightest moons for the year 2017.

3

3

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

April 5, 2017 at 3:55 pm

Thanks Bob. I think I most enjoy watching Jupiter around the times of quadrature, when Jupiter is 90 degrees away from the Sun in the sky, rather than opposition, when Jupiter is 180 degrees away from the Sun. Around opposition you have to stay up until midnight (1 am daylight saving time) to see Jupiter high in the sky. At western quadrature, about three months before opposition, Jupiter is high in the south before sunrise, and at eastern quadrature, three months after opposition, Jupiter is high in south after sunset. Around quadrature, those of us with day jobs can see Jupiter at his best and still get a good night's sleep. While it's true that Jupiter looks biggest around opposition, Jupiter *always* looks pretty big in even a small telescope. Observing when Jupiter is at maximum altitude above the horizon is the most important factor in getting good views.

The geometry of Jupiter and the moons is most interesting around quadrature, when the shadows of Jupiter and the moons fall at the greatest possible angle away from the objects as seen from Earth, so you can see a moon disappear into eclipse a good distance from Jupiter's disk at western quadrature, or suddenly pop into view as the moon emerges from eclipse away from Jupiter's disk at eastern quadrature. This is quite dramatic! When the moons pass in front of Jupiter, around western quadrature you can see a moon's shadow on Jupiter's cloud tops while the moon is still visible to the east of Jupiter, or watch the moon move off Jupiter's face while the moon's shadow is still on the planet, around eastern quadrature. Also, around quadrature Jupiter's limb looks a bit darker and more squashed on the side that's farther from the Sun from our perspective, which makes the planet look a bit more three-dimensional to me.

I definitely make a special effort to look at Jupiter around opposition, but for me the prime Jupiter observing season lasts about six months of the year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 5, 2017 at 4:05 pm

Hi Anthony,

Excellent points! I totally agree with the quadrature timing for moon phenomena especially eclipses and to a good degree, transits too. Though I still like trying to see both a moon and its shadow simultaneously over the planet closer to opposition. Your comment gives me the idea for a second installment on just the moons once we're past opposition. Thanks for writing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

April 5, 2017 at 5:32 pm

Thanks Bob. I'm looking forward to the next episode of the Jovian saga!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.