As if to celebrate our planet's cosmic connections, the annual Lyrid meteor shower will shoot off silent fireworks on Earth Day this Sunday. We explore the shower's origin and how best to view and photograph it.

S&T diagram

Great news for the Lyrids. This annual meteor showers happens in a dark, moonless sky this year. Although active now through late April, peak meteor numbers are expected Sunday morning, April 22nd before dawn.

The Lyrids typically produce 10–20 meteors per hour that appear to radiate from a point in the sky just west of Vega in the constellation Hercules. Before constellation boundaries were standardized in 1930, the radiant of the shower was associated with the constellation Lyra, hence the name.

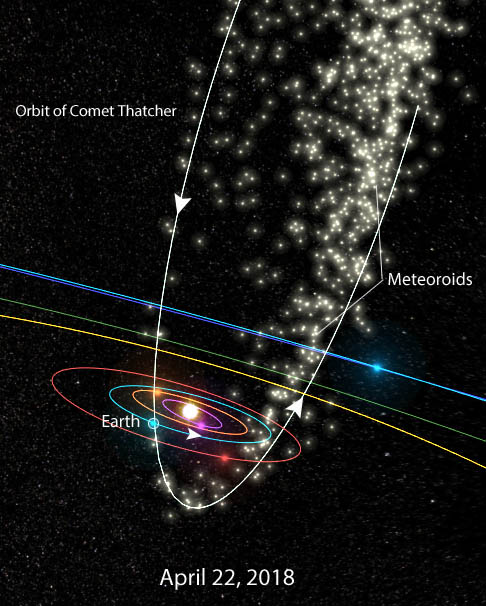

Most meteor showers originate with comets, and the Lyrids are no exception. Its parent is the long-period Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1), which orbits the Sun every 415 years. New York amateur A. E. Thatcher discovered it with his 4.3-inch refractor on April 6, 1861. Six years later, Johann Gottfried Galle (discoverer of Neptune) did the math and found that the comet and the shower were related.

The Lyrids are a reliable if modest shower, but every 60 years or so they show much stronger activity. The last outburst occurred in 1982 when over 100 meteors per hour were seen by some observers. Peter Jenniskens in his book Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets predicts the next Lyrid flare-ups will likely happen in 2040 and 2041. While Comet Thatcher won't come round again until about the year 2276, meteor scientists hypothesize that these cyclic outbreaks may be caused by a recent breakup of Comet Thatcher that deposited a crumbling fragment in a 60-year orbit.

While their numbers may not match the more familiar August Perseids, the Lyrids have at least one claim to fame — no modern shower has been recorded as far back in time. Chinese court astronomers reported a Lyrid outburst on March 16, 687 BC when "in the middle of the night, stars fell like rain."

Meteor data from Peter Jenniskens, visualization by Ian Webster

In current times, the Lyrids retain their fame for a different reason. After more than three months of zilch for meteor showers, they burst on the scene like a wave of spring robins, opening the door for more to follow: the Eta Aquarids in May; July's Delta Aquarids; and the Perseids in August.

The best news of all is that the Moon will be out of the sky for the shower and it stays out of the picture for the maxima of the Perseids, Orionids, Leonids, and Geminids. (Okay, the Orionids will get dinged with a 4 a.m. moonset, but that will still leave almost 2 hours of peak viewing before dawn.) That makes 2018 an exceptional year for meteor-gazing.

Watching the Lyrids is easy. Once the thick crescent Moon sets around 1 a.m., the radiant will have climbed halfway up in the eastern sky, high enough to begin your Lyrid vigil. Better yet, go to bed early and then get up closer to 3 a.m. when the radiant stands some 60° up in the southeastern sky. Without a horizon to cut off shower members that shoot below the radiant, you'll see the maximum number possible.

NASA / MSFC

Maybe my perspective is skewed since we just had a big snowstorm here in Minnesota, but I suggest dressing warmly in hat, gloves, and boots, since you'll be lying still for a time. My favorite observing instrument is a reclining chair like the webbed variety you've probably got stored away in your garage. Angle the chair to face southeast, flop down, and cover yourself with a wool blanket or unzipped sleeping bag. The more light-pollution-free your observing site, the more meteors you'll see. If you're hardy, start at 2 a.m. and watch till the start of dawn (~5 a.m.). If somewhat less hardy, 3–5 a.m. is perfect.

Lie back, relax, and let your cares float away as you anticipate the next flaming morsel of Comet Thatcher. Watching and waiting for the each flash of light in the quiet of the night makes for a soothing form of meditation. I usually keep an informal count, but if you'd like to contribute your observations so meteor researchers can better understand and characterize the Lyrids, register for free with the International Meteor Organization, then download a report form here.

Yuri Beletsky

Lyrids will appear to stream from the radiant, which is a perspective effect caused by incoming meteoroids from Comet Thatcher arriving at Earth on parallel paths, the same way snowflakes in your headlights at night appear to be coming from a point in the distance as you drive down the road. Traveling at 46 kilometers per second, comet dust strikes the atmosphere about 105 kilometers above Earth's surface, tunneling through and briefly ionizing the air to create a momentary streak of glowing light we see as a meteor. The Leonids, fastest of the meteor showers, impact the air at 72 km/sec.

Bob King

Some of us may want a souvenir from the Lyrid shower in the form of a photograph. For that, you'll need a medium- to high-end camera and a tripod. Choose a medium- to wide-angle lens (17–35mm), then set your camera and lens to manual (M setting) and use the live view feature to focus on a bright star. Next, compose a picture that includes the radiant off to one side of the field of view. Meteors away from the radiant leave longer, more dramatic trails. Open the lens to its widest setting, usually f/2.8, 3.5, or 4, set the ISO to 800 or 1600, and expose for 30 seconds.

Check your progress and exposure by looking at the back display. You can manually take one photo after another or you can automate the process by using an intervalometer, which will snap continuous time exposures hands-free. There's no better tool for meteor shower photography.

All we need now is good weather. With the shower maximum coinciding with Earth Day, what better way to reaffirm the planet's cosmic connection than watching sparks fly as we plow into comet dust. May clear skies meet your eyes when Sunday morning comes.

7

7

Comments

Graham-Wolf

April 18, 2018 at 9:52 pm

Sorry, Bob.

Lyrid shower just not observable from NZ.... too far North!

Regards from 46 South, Dunedin, NZ.

Graham W. Wolf.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 19, 2018 at 10:46 pm

Sorry, Graham! You're as far south as I am north. Better luck with the Eta Aquarids 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ajbeto

April 20, 2018 at 10:11 am

Profesor Bob King: Le saludo desde Loja /Ecuador, estoy situado a 4° Sur. ¿Es posible ver este dom ingo la lluvia de estrellas de las Lyrydas, desde esta ´posición? Solo espero que halla buen clima. Gracias y felicitaciones por su Blog de astronomía.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 20, 2018 at 5:02 pm

Ajbeto,

¡Sí, es posible ver las Líridas de Loja! El radiante tendrá aproximadamente 38 grados de altura en el cielo del norte una hora o dos antes del amanecer. ¡Cielos despejados!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Myth

April 20, 2018 at 5:44 pm

I'll be there for the show on the evening of the 22nd from 8PM-2AM, Point Beach State Park, WIS. Great place, pretty dark, and Lake Mich as the back drop. Here's to clear skies boys and girls, and don't strain your necks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

George Gliba

April 21, 2018 at 12:22 pm

Bob,

I saw 16 Lyrids in two hours this morning from 1:04 AM to 3;04 AM EDT from Mathias,

West Virginia with a limiting magnitude of around 6.4 magnitude. However, the average

Lyrid was a rather faint 3.6 magnitude. As tomorrow morning is the peak on Earth Day,

the rates and average brightness may be a lot better. Unfortunately, our forecast calls for

mostly clouds then. Still not bad show this morning.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Curt

April 21, 2018 at 1:21 pm

Hi George. Nice to hear your report from Mountain Meadows. These days I do my WV viewing from Kile Knob, except during winger.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.