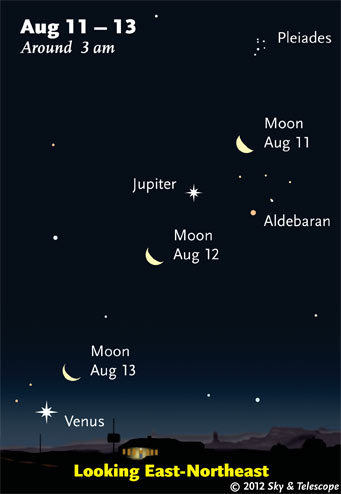

Night owls can watch the weird waning Moon with Jupiter, Venus and company. The Moon (enlarged three times here) is positioned for viewers near the middle of North America.

Sky & Telescope diagram

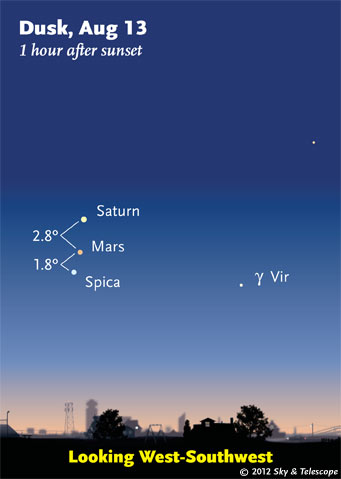

Don't miss the Saturn-Mars-Spica lineup in evening twilight on Monday and Tuesday the 13th and 14th. The lineup fits easily in the view of most binoculars. Notice how pointlike Spica twinkles much more than the planets. Planets' apparent disks are made of many points, which twinkle nearly independently of each other, thus averaging out.

Sky & Telescope diagram

As the Moon wanes further, dawn is the time to catch it descending toward Mercury.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Friday, August 10

Saturday, August 11

The thick waning crescent Moon rises by 1 or 2 a.m. (with Jupiter above it). But its modest light, notes the International Meteor Organization, "should be considered more of a nuisance than a deterrent."

You're also likely to see occasional Perseids for many nights before and after. See our article Perseids at Their Prime.

Sunday, August 12

Monday, August 13

Tuesday, August 14

Wednesday, August 15

Thursday, August 16

Friday, August 17

Saturday, August 18

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

Sky Atlas 2000.0 (the color Deluxe Edition is shown here) plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5. That includes most of the stars that you can see in a good finderscope, and typically one or two stars that will fall within a 50× telescope's field of view wherever you point. About 2,700 deep-sky objects to hunt are plotted among the stars.

Alan MacRobert

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The standards are the little Pocket Sky Atlas, which shows stars to magnitude 7.6; the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 8.5); and the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts effectively.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic if dated Burnham's Celestial Handbook.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? I don't think so — not for beginners, anyway, and especially not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (able to point with better than 0.2° repeatability). As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their invaluable Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury is having a good apparition low in the dawn, brightening daily. Look for it above the east-northeast horizon, far lower left of brilliant Venus. Mercury is only magnitude +0.9 on the morning of August 11th but brightens to –0.4 by the 18th.

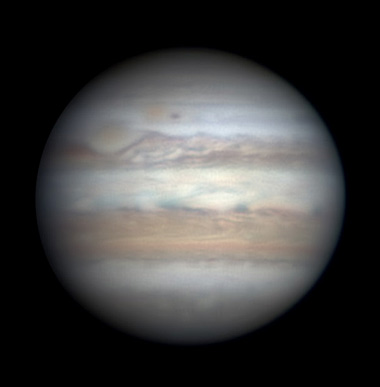

Jupiter on August 8th. The brownish North Equatorial Belt (below center) remains extremely broad. Really, what we're seeing is a combination of the NEB and the North Temperate Belt below it. Above center, the South Equatorial Belt is disturbed by the whitish wake of the Great Red Spot. The GRS itself now appears paler orange than Oval BA ("Red Spot Junior") just to its upper right here. Oval BA is catching up to the GRS and should pass it in coming weeks, writes imager Christopher Go, perhaps with interesting interactions.

Venus and Jupiter (magnitudes –4.5 and –2.2) shine dramatically in the east before and during dawn. They've widened to about 24° apart, with Jupiter high to Venus's upper right. They're in Gemini and Taurus, respectively. Look for orange Aldebaran, much fainter, 5° right or lower right of Jupiter. Near Aldebaran are the Hyades, and above are the Pleiades.

The asteroids Ceres and Vesta, magnitudes 9.0 and 8.2, are in Jupiter's vicinity too! See article and finder charts: Ceres and Vesta, July 2012 – April 2013.

Mars, Saturn, and Spica (very similar at magnitudes 1.1, 0.8, and 1.0 respectively) are bunched low in the west-southwest at dusk, far below bright Arcturus. They form a triangle 4½° tall that changes every day. Mars passes between Saturn and Spica on Monday and Tuesday, August 13th and 14th — turning the triangle into a slightly curved, nearly vertical line.

Uranus (magnitude 5.8, at the Pisces-Cetus border) and Neptune (magnitude 7.8, in Aquarius) reach good heights in the southeast by late evening. Finder charts for Uranus and Neptune.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 4 hours.

Like This Week's Sky at a Glance? Watch our weekly SkyWeek TV short. It's also playing on PBS!

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.