Friday, October 6

• The Moon, just past full, rises in the east in late twilight. As night arrives, look for the two brightest stars of Aries to the Moon's upper left by about a fist and a half at arm's length. The stars are 4° apart (less than half a fist) and lined up almost horizontally. Can you see that the brighter one — Hamal, on the left — has an orange tint?

Saturday, October 7

• The Great Square of Pegasus balances on its corner high in the east at nightfall. For your location, when it is exactly balanced? That is, when it the Square's top corner exactly above its bottom corner? It'll be sometime after the end of twilight, depending on both your latitude and longitude. Try lining up the stars with the vertical edge of a building.

Sunday, October 8

• The starry W of Cassiopeia stands high in the northeast after dark. The right-hand side of the W (the brightest side) is tilted up.

Look along the second segment of the W counting down from the top. Notice the dimmer naked-eye star partway along that segment. That's Eta Cassiopeiae, magnitude 3.4, a Sun-like star just 19 light-years away with an orange-dwarf companion. It's a lovely binary pair in a telescope, with an easy separation of 20 arcseconds.

Left of Eta Cas along the segment is a fainter, much wider pair: Upsilon1 and Upsilon2 Cassiopeiae, separation 0.3° (1,200 arcseconds). This pair consists of two orange giants, and they're unrelated to each other; they're 200 and 400 light-years from us.

See also October 12 below.

• The waning gibbous Moon rises in midevening with the Pleiades to its upper left and Aldebaran and the Hyades to its lower left.

Monday, October 9

• As the last of twilight fades away, look above the northeast horizon — far below Cassiopeia — for bright Capella on the rise. How high you'll find it depends on your latitude. The farther north you are, the higher it will be.

Tuesday, October 10

• Sometime around when nightfall is complete, you'll find zero-magnitude Arcturus low in the west-northwest at the same height as zero-magnitude Capella in the northeast. When this happens, turn to the south-southeast, and there will be 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut at the same height too — if you're at latitude 43° north. Seen from south of that latitude Fomalhaut will appear higher; from north of there it will be lower.

Wednesday, October 11

• The last-quarter Moon rises around 11 or midnight tonight, depending on your location. Once the Moon is well up you'll see that it's in Gemini, with Castor and Pollux shining to its left. Farther to its right you'll get an early look at Orion — your first of the season?

Thursday, October 12

• After dark, spot the W of Cassiopeia high in the northeast, it's standing almost on end. The third segment of the W, counting from the top, points almost straight down. Extend it twice as far down as its own length, and you're at the Double Cluster in Perseus. This pair of star-swarms is dimly apparent to the unaided eye in a dark sky (use averted vision), and it's visible from almost anywhere in binoculars. It's lovely in telescopes.

Friday, October 13

• Now that we're in mid-October, Deneb has replaced Vega as the zenith star soon after nightfall (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes) — and, accordingly, Capricornus has replaced Sagittarius as the most notable constellation low in the south.

Saturday, October 14

• Vega is the brightest star in the west these evenings. Less high in the southwest is Altair, not quite as bright. Just upper right of Altair, by a finger-width at arm's length, is little orange Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae). Straight down from Tarazed runs the stick-figure backbone of Aquila, the Eagle.

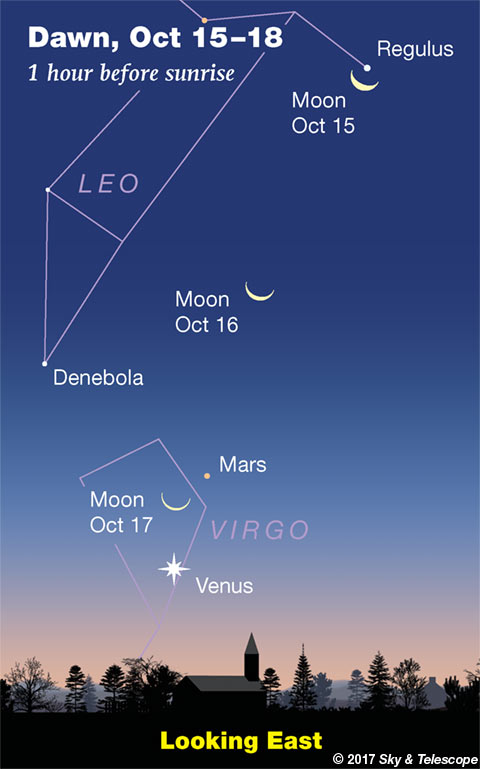

• Early on Sunday morning the 15th, the bright limb of the waning crescent Moon occults Regulus for telescope users in much of North America. The disappearance happens during dawn for the East and earlier in darkness farther west. The West Coast misses the disappearance; the Moon won't have risen yet.

But then, up to an hour or more later, Regulus reappears from behind the Moon's dark limb. This will be a naked-eye event for much of the USA and southeastern Canada! The reappearance will be "arguably the best lunar occultation of the year for the US, with the Moon only 20% sunlit," writes David Dunham of the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA). "And for those with telescopes of about 10 inches or larger, it might provide a fleeting opportunity to see Regulus’s elusive, 12th-magnitude white-dwarf companion, discovered in 2005, just before the blazing primary emerges. The only other time that the companion was imaged was during an occultation of Regulus by the asteroid 268 Adorea that Joan and I recorded with a 10-inch 'suitcase' telescope from Papua New Guinea on Oct. 13, 2016."

Here are a map and detailed timetables of the disappearance and reappearance for many locations, including the altitudes of the Moon and Sun at those times. (The page consists of three long tables, not very clearly divided: first the disappearance, then the reappearance, then the locations of cities.)

To record the grazing occultation along the northern limit, writes Dunham, "I believe the best place will be Bemidji, MN, but other places, such as Billings, MT, and Bismarck, ND, will be good too, as well as rural parts of Ontario and Quebec." Details of the graze.

________________________

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations! They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, is the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts with a telescope.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, or the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (meaning heavy and expensive). And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury is hidden behind the glare of the Sun.

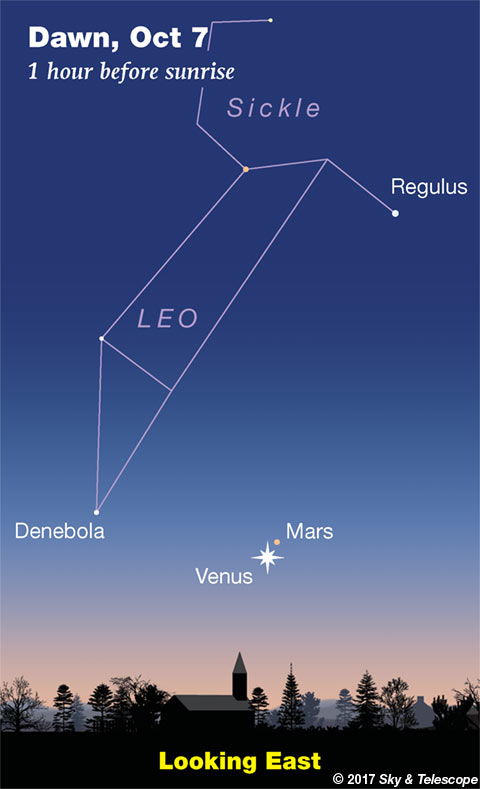

Venus is the bright "Morning Star," (magnitude –3.9) is low due east in the dawn. Just above it is faint Mars, magnitude +1.8, only 1/200 as bright. They were in conjunction on the morning of October 5th and are now drawing apart. On the morning of Saturday the 7th they're 1° apart (at dawn for North America), and by the 14th they're 5° apart. Venus is getting lower, Mars higher.

Why their great brightness difference? Whenever Mars appears anywhere near Venus, it seems to get scared and fade. That's because Venus is never seen far from our line of sight to the Sun. Whenever Mars is anywhere near our line of sight to the Sun, it has to be on the far side of its orbit from us: about as far and faint as it gets.

Jupiter is hidden deep in the glare of sunset.

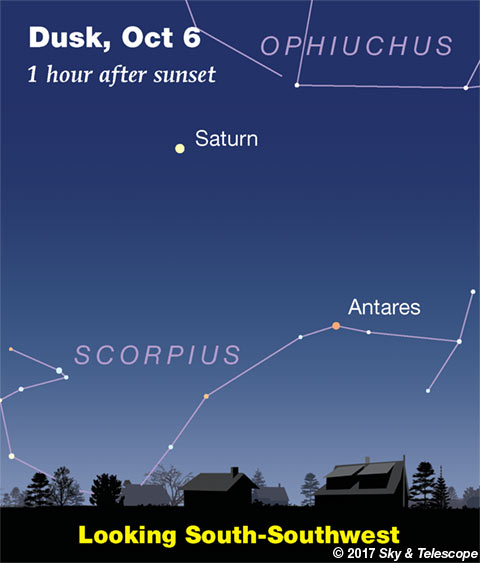

Saturn (magnitude +0.5, in Ophiuchus to the right of the Sagittarius Teapot) glows low in the southwest at dusk. It soon sinks lower and sets.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in Pisces) and Neptune (magnitude 7.8, in Aquarius) are up in the east and southeast, respectively, by mid-evening. Use our finder charts online or in the October Sky & Telescope, page 50.

______________________

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time (UT, UTC, GMT, or Z time) minus 4 hours.

______________________

"This adventure is made possible by generations of searchers strictly adhering to a simple set of rules. Test ideas by experiments and observations. Build on those ideas that pass the test. Reject the ones that fail. Follow the evidence wherever it leads, and question everything. Accept these terms, and the cosmos is yours."

— Neil deGrasse Tyson, 2014

______________________

"Objective reality exists. Facts are often determinable. Carbon dioxide traps global heat. Vaccines save lives. Bacteria evolve to thwart antibiotics, because evolution. Science and reason are not a political conspiracy. They are how we discover reality. Civilization's survival depends on our ability, and our willingness, to do so."

— Alan MacRobert, your Sky at a Glance editor

______________________

. . . Because "Facts are stubborn things."

— John Adams, 1770

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.