December 9, 2013

Contact:

Alan MacRobert, Senior Editor, Sky & Telescope

855-638-5388 x2151, [email protected]

Tony Flanders, Associate Editor, Sky & Telescope

855-638-5388 x2173, [email protected]

The annual Geminid meteor shower, one of the best shooting-star displays each year, returns to our skies late this week. Skygazers and nature enthusiasts throughout the Northern Hemisphere will be out watching. Anyone can join in. You need no equipment and no special knowledge.

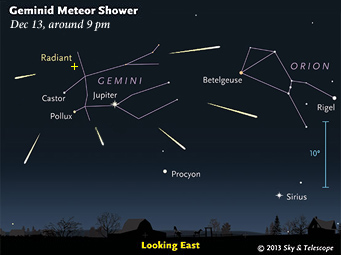

Click for high quality version (HD format), free for use with credit to SkyandTelescope.com.

Every year in mid-December, Earth passes through a stream of rock bits that are being shed by a superheated asteroid named 3200 Phaethon. In 2013 we should see the meteor shower at its most active from 9 or 10 p.m. (local time) on Friday December 13th until the first light of dawn Saturday morning.

"We'll have interference from moonlight in the sky this year," says Robert Naeye, editor in chief of Sky & Telescope magazine, "but the brighter meteors will shine through anyway. You'll probably see quite a few."

For real night owls, the Moon sets about an hour before the first glimmer of dawn, affording a one-hour window of dark sky for serious meteor counters.

The shower will also be active for a few nights before Friday, and the Moon sets about an hour earlier for each morning before the 14th. The Geminids drop off more quickly after that date.

How to Watch

"Bundle up as warmly as you can," says Alan MacRobert, a senior editor at Sky & Telescope. "Go out around 9:00 or preferably later. Find a spot with an open view of the sky and no lights to get in your eyes. Bring a reclining lawn chair, face it away from the Moon, lie back, gaze into the stars, and be patient."

You might see a Geminid every couple of minutes on average, depending on the brightness of your sky.

Oddball Space Bits

As meteor showers go, the Geminids are unusual in several ways. This is often the richest reliable shower of the year, and it seems to be strengthening from decade to decade. It becomes nicely active as early as mid-evening, so you don't have to wait until after midnight as for many other showers. Geminids are relatively slow, hitting the top of Earth's atmosphere at 36 km (22 miles) per second, hardly more than half the speed of the Perseids, Orionids, and Leonids.

Also, these meteors often appear yellowish, and their deep plunges into the atmosphere betray them as dense bits of rock rather than fluffy dust clods like most cometary meteors.

In fact they come not from a comet but a tiny asteroid, Phaethon, that is itself an oddball. It's in a tight, highly elliptical orbit that, every 1.43 years, brings it three times closer to the Sun than Mercury's average distance. This means the Sun repeatedly shines on it 50 times brighter than sunlight on Earth.

How does it produce the Geminid meteoroid stream? Solar-system researchers David Jewitt and Jing Li at UCLA say they've figured it out, reports Sky & Telescope. Astronomers had thought that Phaethon — discovered as recently as in 1983 and only 3 miles (5 km) wide — had to be an old comet nucleus. But during its loops around the Sun every 17 months its surface roasts to more than 1300°F (700°C), so all water and other volatiles must have been baked out ages ago. So, how could it continue to shed any particles at all?

Jewitt and Li found proof that it does. NASA's two STEREO spacecraft, designed to observe the Sun, are also able to see Phaethon when it's nearest the Sun despite its tiny size. STEREO images show that Phaethon brightens and sheds a trail of dust and debris when it's in the most intense heat. With no volatiles left in Phaethon to vaporize and carry particles away, the two astronomers propose that its bare rock cracks and crumbles by thermal fracturing. Jewitt calls Phaethon a "rock comet."

Become a Meteor Counter

Many amateur watchers plan to do scientific meteor counts. The International Meteor Organization always wants more observers around the globe. You'll need to follow the IMO's standardized instructions so that your counts can be meaningfully compared with others. See the IMO's website and also Sky & Telescope's introduction to advanced meteor observing.

For more skywatching information and astronomy news, visit SkyandTelescope.com anytime or pick up Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy since 1941.

Sky Publishing (a New Track Media company) was founded in 1941 by Charles A. Federer Jr. and Helen Spence Federer, the original editors of Sky & Telescope magazine. In addition to Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.com, the company publishes two annuals (Beautiful Universe and SkyWatch), as well as books, star atlases, globes, and other fine astronomy products.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.