A collaboration between professional and amateur astronomers is producing a careful map of stellar brightnesses and colors across the entire night sky.

When I flip through the press conference schedule for an American Astronomical Society meeting, I usually don’t expect to see a presenter listed from a professional-amateur collaboration. So I was pleasantly surprised to find that Arne Henden, Director of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, was speaking at the AAS summer meeting this week in Anchorage, Alaska.

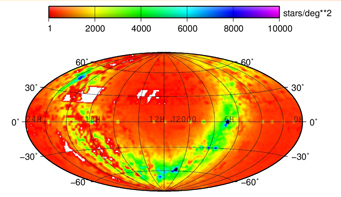

This map shows the current coverage of the primary AAVSO All-Sky Photometric Survey, with two visits per field. The white spot over New Mexico is due to the July monsoon season and fires in the state. About 95% of the sky has been covered; the remainder has one visit.

AAVSO / E. Los

As Henden announced yesterday, the sixth interim release is out for the AAVSO Photometric All-Sky Survey, a pro-am collaboration that’s taking careful color and brightness measurements, through five filters, of stars between 10th and 17th magnitude. This magnitude range has never before been systematically surveyed, although it does partly overlap with previous all-sky work in both photometry and astrometry (high-precision position measurements, such as those done by the ESA’s Hipparcos satellite and the U.S. Naval Observatory’s UCAC program).

The pro-am team behind the project also chose these magnitudes because they’re the ones typically observed in backyard telescopes.

The APASS project uses two pairs of 8-inch astrographs, one in New Mexico and the other in Chile. Each pair sits on a Paramount ME mount and is operated remotely to point at the same position on the sky. One scope takes the blue filter exposures (Johnson B and Sloan g’) and the other the redder exposures (Johnson V and Sloan r’ and i’). Each image is 2.9° × 2.9° in size, a field of view that would encompass roughly 90 full moons. So far, the survey has covered roughly 95% of the sky twice and measured the color and brightness of 42 million stars.

“The 8-inch scopes are the right tool for the job,” Henden said during the press conference. “They may look small, but they’re doing frontline, state-of-the-art science.”

APASS uses solely commercial hardware and software, working thanks to private grants and equipment loans from vendors. Originally the project planned to have only one set of 8-inch scopes, using them first in New Mexico from October 2009 to summer 2010 and then moving them to Chile to observe the Southern Hemisphere. Although the team still moved the tried-and-true New Mexico scopes to Chile as planned, an additional grant from the Robert Martin Ayers Science Fund allowed the AAVSO to purchase a second pair of astrographs to put in New Mexico to continue observing the Northern Hemisphere.

Henden says they have already compared their observations against a number of standard fields and found APASS’s photometric precision is about 3%. He expects that to go down to 1-2% by the final release of the catalog in 2014.

Brian Skiff (Lowell Observatory), who’s spent several years compiling a database of high-quality photometry, says he suspects that for the most crowded parts of the sky observers will still need to rely on photometric data taken with bigger telescopes. “But even within its limits, [APASS] should be a boon for observers — both professional and amateur — doing systematic observing of just about any sort,” he adds. It’s a big deal to have reliable magnitudes and colors for these stars done with a standard system: if you have high-precision photometry for stars across the whole sky, you can more accurately (and more quickly) determine brightnesses for variable stars or for new objects such as supernovae — without searching around the sky or your images for something you do have data for. “Folks have wanted a uniform survey like this for a long time.”

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.