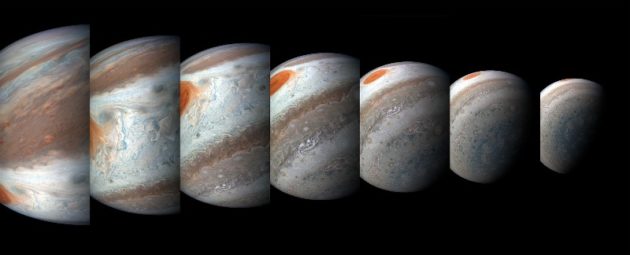

Ahead of a decision on whether to fly the NASA spacecraft over Jupiter's Great Red Spot, hobbyists back on Earth provided crucial intel about the effects of an intruding disturbance.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / MSSS / Gerald Eichstadt / Sean Doran

Planning observations for the Juno spacecraft at Jupiter is a group effort, and Candice Hansen (Planetary Science Institute) should know. As the scientist in charge of JunoCam — one of the cameras onboard the probe — she spends a lot of time chatting with professional and amateur astronomers, keeping tabs on what’s happening in Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere. Their intel is critical to figuring out where to point JunoCam each time the spacecraft makes another close pass over the planet.

But lately, this worldwide network of backyard Jupiter enthusiasts has been helping mission scientists figure out where precisely Juno should fly. Speaking last week at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington, D.C., Hansen described how Juno’s army of amateurs were key players in deciding whether or not to go ahead with an impending flyover of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

Hansen sat down with Sky & Telescope to chat about the upcoming flyby and the role that amateur astronomers played in planning it out.

Juno, which has been in a polar orbit since July 2016, is about halfway through its mission to map out Jupiter’s deep interior. The spacecraft spends most of its time far from the planet, but once every 53 days, it comes in low and fast, zipping from north pole to south pole in roughly 2 hours. Near the equator, the probe hurtles along at roughly 250,000 kilometers per hour (150,000 mph) just a few thousand miles over the cloud tops.

For each of these close approaches, mission scientists can tweak Juno’s speed to control precisely what longitudes it will fly over. While planning the spacecraft’s eighteenth flyby — referred to as perijove 18 in mission parlance — scientists realized they had a chance to make a second pass over the Great Red Spot if they swapped the original plan for perijove 18 with the plan for perijove 23.

But amateur astronomer John Rogers, head of the Jupiter Section of the British Astronomical Association, urged caution. “John warned us that before you make that swap, you might want to make sure the Great Red Spot is even going to be there,” says Hansen.

A disturbance in the sky

Christopher Go

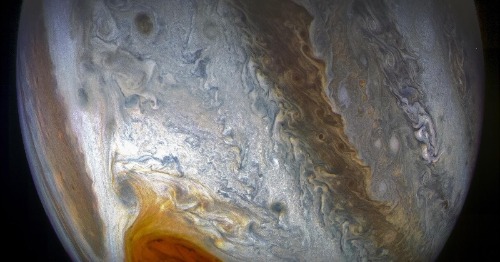

Back during perijove 9 — on October 24, 2017 — JunoCam imaged an atmospheric disturbance not far from the Great Red Spot. Rogers, who keeps tab on the worldwide web of Jupiter hobbyists, recognized what it was right away: the re-appearance of a turbulent morass known as the South Tropical Disturbance. This churning dark smudge occasionally pops at the same latitude as the Great Red Spot . . . and has a history of nudging its more famous cousin.

The South Tropical Disturbance was discovered in 1901 by another amateur, British military officer Percy Molesworth. It stuck around until 1939, lapping the Great Red Spot eight times. Writing in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association in 1997, Richard McKim described Molesworth’s disturbance as a “darkened stretch of the south tropical zone of Jupiter through which the normal pattern of alternating dark belts and bright zones is interrupted.” Since then, it has appeared seven times, with one in 1979 nicely timed for the flyby of the Voyager 2 spacecraft.

Rogers knew this history well, and also knew that the South Tropical Disturbance had a propensity for changing the speed of the Great Red Spot on its east-west trek through Jupiter’s skies. He was concerned that this appearance would make the Red Spot miss the hoped-for meetup with Juno in February 2019.

“We needed to wait as long as we could to see how this was all going to shake out,” says Hansen. She and her colleagues convinced project managers to give them as much time as possible while amateurs sent along updates on how the Red Spot and the Disturbance were getting along.

Ground-based observations showed the Disturbance snuggling up to the Great Red Spot in February 2018. Over the next couple of months, dark gasses swirled around the Spot’s southern boundary as the South Tropical Disturbance once again lapped the ruddy storm. During April’s perijove 12, Juno passed just 10 degrees to the east of the Great Red Spot and saw the Disturbance pulling away, teasing out tendrils of haze in its wake.

Data from amateur astronomers were invaluable, says Hansen. In the end, the team decided to go for it and try for the Red Spot on February’s close approach. “We might not fly right over the middle of it,” she says, “but it will be close enough to do the science that we want to do.”

Green light for the Red Spot

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / MSSS / Kevin M. Gill

This isn’t the first time that Juno has buzzed the Great Red Spot. On July 2, 2017, (perijove 7) the spacecraft went right over with its microwave antenna probing the roots of the mammoth storm. Those data revealed that the Spot — spanning 1.3 times the width of Earth — extends at least 300 km (200 miles) below the cloud deck.

During the next pass, Juno will orient itself to probe the gravity field over the storm, which will reveal how much excess mass is swirling around down there. Researchers map out Jupiter’s gravity by tracking slight changes in Juno’s speed, revealed by Doppler shifts in the radio link back to Earth. By combining the microwave and gravity data, scientists should learn a lot about the Spot’s vertical structure, says Hansen.

Amateurs were always going to be an integral part of the mission. JunoCam was designed to be a citizen science camera, with observations from hobbyists on Earth providing a continuously updated “big picture” view of where to look next. And without a dedicated team of professionals cleaning up JunoCam’s images, the mission has provided the raw data to an eager public who have gone on to produce surreal Jovian scenes that often blur the line between science and art.

“One of the really good things about amateur astronomers is that they can go out in their backyard on any given night and decide what they want to look at,” says Hansen. “They are actually the best-positioned community to see when something changes. . . . We’ve been relying on them since the beginning of the mission to keep on top of what’s going on at Jupiter.”

Until now, though, those interactions were limited to decisions about where to point the camera. But with the emergence of the South Tropical Disturbance and its potential effect on the trek of the Great Red Spot, notes Hansen, “that’s the first time that it’s really affected our mission design.”

References:

C. J. Hansen et al. "Images of Jupiter: Science and Art." 2018 Meeting of the American Geophysical Union. December 11, 2018.

J. H. Rogers et al. “The New South Tropical Disturbance and its Interaction with the Great Red Spot.” European Planetary Science Conference. September 18, 2018.

R. J. McKim. “P. B. Molesworth's Discovery of the Great South Tropical Disturbance on Jupiter, 1901.” Journal of the British Astronomical Association. October 1997.

1

1

Comments

fif52

December 20, 2018 at 6:27 pm

why miss it? the most important feature on the surface (about it). on the surface there is almost certainly a crater where the great red spot is a cloud formation around a deeper part, mostly due to down drafting winds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.