In 1900, a man named John Nevil Maskelyne filmed a solar eclipse — the first movie of its kind.

On May 28, 1900, amateur filmmaker John Nevil Maskelyne captured the first-ever movie of a solar eclipse from the small town of Wadesboro, North Carolina.

John Nevil Maskelyne (not to be confused with the eponymous Nevil Maskelyne, a British Astronomer Royal who lived until 1811) shot this film of a solar eclipse on May 28, 1900, using what he called a kinematograph telescope. Seven seconds into the movie, a tiny bead of sunlight escapes through a lunar valley and creates a diamond ring shape around the Sun. The rest of the movie shows a faintly oblate solar atmosphere that’s brighter near the equator and dimmer near the poles.

Royal Astronomical Society / British Film Institute

The reconstructed film, released by the Royal Astronomical Society and British Film Institute, shows a massive circle of superhot, million-degree gas flying off the surface of the Sun. This corona is a hundred times hotter than the visible surface, but a million times dimmer.

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich

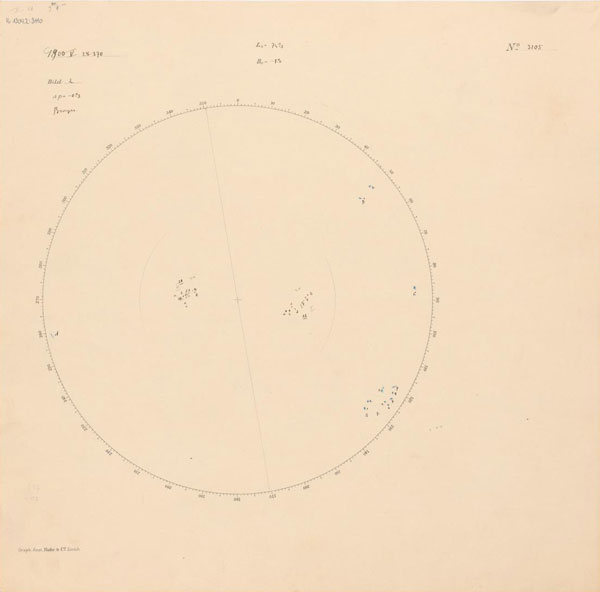

Colleagues at the British Astronomical Association who joined Maskelyne in Wadesboro would have known that the year 1900 marked a particularly calm phase in the Sun’s 11-year cycle. A drawing of the Sun from the same day shows a mostly blank solar surface flecked with a few small spots.

On the day of the eclipse, however, Maskelyne was only focused on making a technically sound film. He knew that, as the Moon slid across the solar disk, the bright and clear summer day would turn into a minute and a half of silvery darkness. He compensated for this change in brightness by adjusting the exposure of each image.

After the eclipse, Maskelyne brought his film back to England. But it disappeared into the Royal Astronomical Society’s archives until Sian Prosser, the Royal Astronomical Society’s Librarian and Archivist, and her colleagues discovered it a few years ago. Bryony Dixon, the curator of silent film at the British Film Institute, and her colleagues restored and digitized the film.

Maskelyne wanted to convince astronomers to embrace cinematography. At the time, few people knew about filmmaking — the entire genre had emerged only two decades before — and fewer still turned their cameras to the night sky. Astronomer David Peck Todd did capture 147 frames of Venus transiting the face of the Sun in 1882, which the Lick Observatory later digitized. But Todd probably wasn’t thinking about filmmaking when he shot these frames, compiled into a movie more than a century later:

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story noted a possible prominence eruption 28 seconds into the movie. However, this feature is likely an artifact, such as a scratch or flaw in the emulsion.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.