A database run by the American Association of Variable Star Observers will organize and archive data on transiting exoplanets collected by amateur astronomers.

JPL-Caltech / NASA

A putative frigid planet orbiting Barnard’s star, the second closest star system to the Sun, made headlines last week. The discovery relied on 20 years of data gathered from seven major observatories. What’s less well known is that amateur astronomers also pitched in by providing intel on the star’s fluctuating brightness.

Searching for planets outside our solar system might seem like a task best left to the pros. But amateurs have quite a bit to contribute as well. That’s the impetus for a new online database for collecting and archiving amateur exoplanet observations.

The database, managed by the non-profit American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), will provide a central hub for the long-term monitoring that is essential for refining the orbits and properties of known exoplanets as well as looking for hints of worlds that have yet to be discovered.

The AAVSO announced the venture on November 16th at its annual meeting at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz. This new tool builds on AAVSO’s century-long worldwide mission to support observers of variable stars.

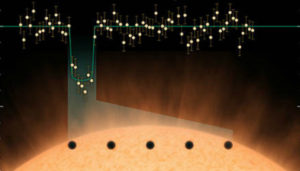

Amateurs, like most pros, can’t directly see planets beyond the solar system. But they can monitor a star and watch for dips in the brightness caused by a planet passing between its sun and Earth — a technique known as the transit method. The amount of blocked starlight relates to the size of the planet while the frequency of the dips reveals info about the planet’s orbit.

Hobbyists are uniquely suited to these kinds of observations. Unless a planet is snuggled up close to its star, these transits may happen just once every several months or even years. Time on big professional telescopes is precious and often difficult to devote to this kind of work. Amateurs, meanwhile, can stare at a planet-hosting star for as long as they like.

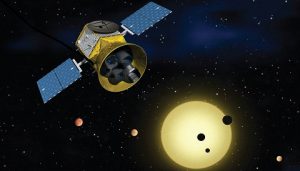

NASA

The AAVSO says that this database is especially important with the recent launch of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which in April began its two-year mission to scan over 90% of the sky for planets orbiting many of the brightest and closest stars. Unlike the Kepler space telescope (R.I.P.), which initially stared at one patch of sky for nearly 4 years, TESS will hop from one region to another, with most areas getting as little as 27 days of coverage. Ground-based monitoring from pros and amateurs will therefore be essential to refining our knowledge about the worlds that TESS digs up.

What’s more, amateurs may even be able to look for worlds that have yet to be discovered. An unseen planet can show itself by tugging on planets that are already known. This gravitational tug-of-war causes the known planet to transit its star either a little early or a little late. Repeated observations of these “transit timing variations” can reveal not only the presence of another planet but also details about its mass and orbit.

At AAVSO’s exoplanet database, observers can upload their observations and sift through data submitted by others. Users provide information about their equipment, where and when they made their observations, links to images of the target star, and a text file that lists measurements of the star’s brightness. Visitors can also search by star, exoplanet, date range, and even specific observers for extant data.

“This [database] emphasizes the value that nonprofessionals bring to the field of science,” said AAVSO Executive Officer Stella Kafka in a press release. “People with moderate means can contribute from the ground to the knowledge base of the community. In principle, one can see the AAVSO as an international collaboration between professional and non-professional astronomers, working together to understand some of the most exciting phenomena in the universe.”

Detailed instructions for using this resource are provided at the database website.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.