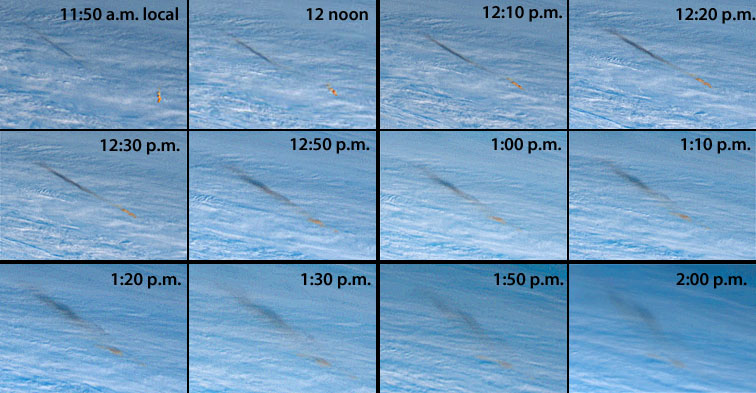

A powerful fireball exploded over the wilds of eastern Russia last December. Satellites captured the whole thing.

Japan Meteorological Agency

I was probably picking up a last-minute Christmas gift when it happened. Last December 18th at 11:48 a.m. local time, a meteoroid exploded with 10 times the force of the Hiroshima atomic bomb over the Bering Sea. It became the second most powerful meteor blast this century, after the Chelyabinsk explosion in 2013 that released the energy equivalent of 20 to 30 atomic bombs.

Japan Meteorological Agency

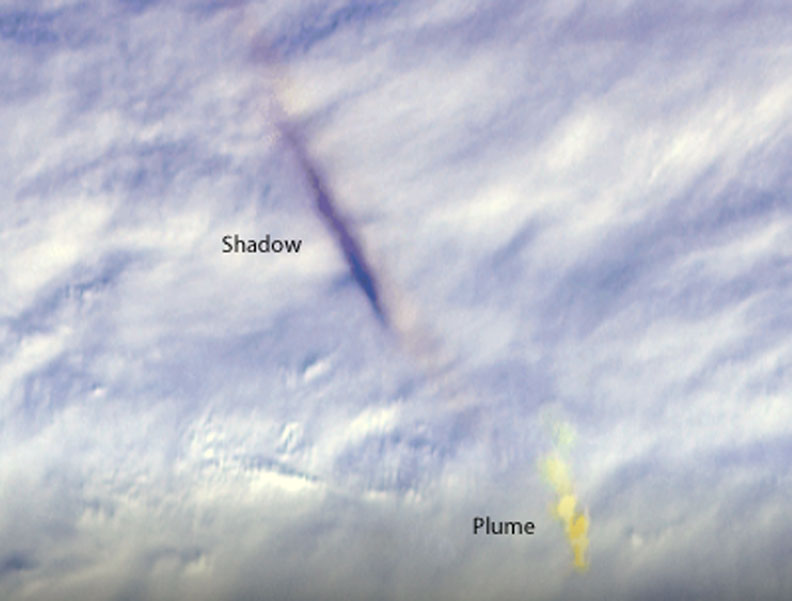

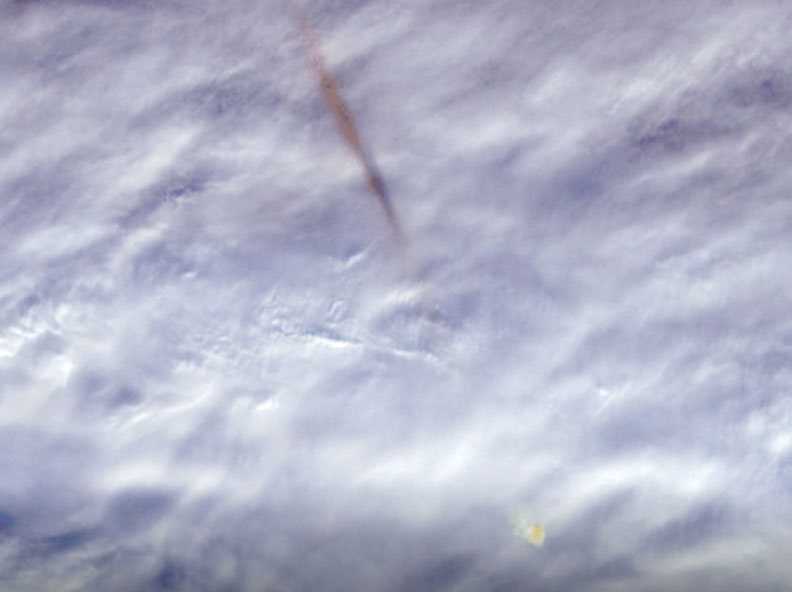

Had there been eyewitnesses, we'd have known about the Bering blast within minutes, but it happened beneath the cloud deck in a sparsely populated region off the east coast of Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula (58.6°N, 174.2°W). Military satellites designed to look for nuclear explosions picked up the blast, as did more than 16 infrasound detectors worldwide. Luckily for us, so did the Japanese Himawari 8 and U.S. Terra satellites, which took striking images of the evolving orange plume of meteoric dust and the shadow it cast on the clouds below during its atmospheric passage.

NASA/GSFC/LaRC/JPL-Caltech, MISR Team

I originally thought the orange glow pictured in the images was part of the ionized trail left by the speeding meteoroid, but this can't be possible because traces of the color lingered for about 90 minutes, far too long. While trains can last for many minutes, the colorful, bright trail typically lasts only seconds.

NASA/GSFC/LaRC/JPL-Caltech, MISR Team

The Sun stood about 11° at the time of impact and slowly declined thereafter, so the color likely comes in part from the low sun angle which tends to "warm" things up. Peter Brown, a meteor scientist and planetary astronomer at the University of Western Ontario, suggested in an e-mail communication the back-scattering properties of the meteoroid dust removed blue from the trail and further reddened its appearance.

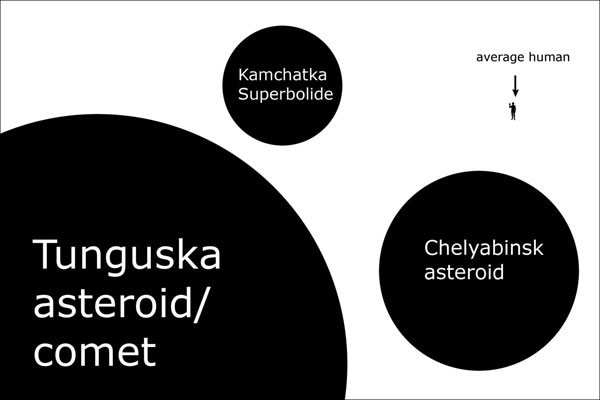

Peter Brown first tweeted the news of the event on March 8th. Now it's making the rounds of the internet in various forms including being falsely reported on a few sites as occurring over Greenland. Based on the imagery and infrasound data, the asteroid responsible for all the fuss measured about 10 meters across, or a little larger than a two-story building. It packed the force of ~176 kilotons of TNT and would have made a spectacular sight. Perhaps ground video may yet surface.

Alex Chamberlin / JPL-Caltech

Given the magnitude of the blast it's very possible that meteorites fell, likely in the Bering Sea. The Cuba meteorite fall on February 1st produced a far less powerful blast — only in the kiloton range — but made a memorable sonic boom and showered the region with many stony meteorites. Significant airbursts like the Kamchatka meteor occur about three to four times a century.

Fireball explosion over Pinar del Rio, Cuba, on February 1st. You can hear the explosion at the 55-second mark.

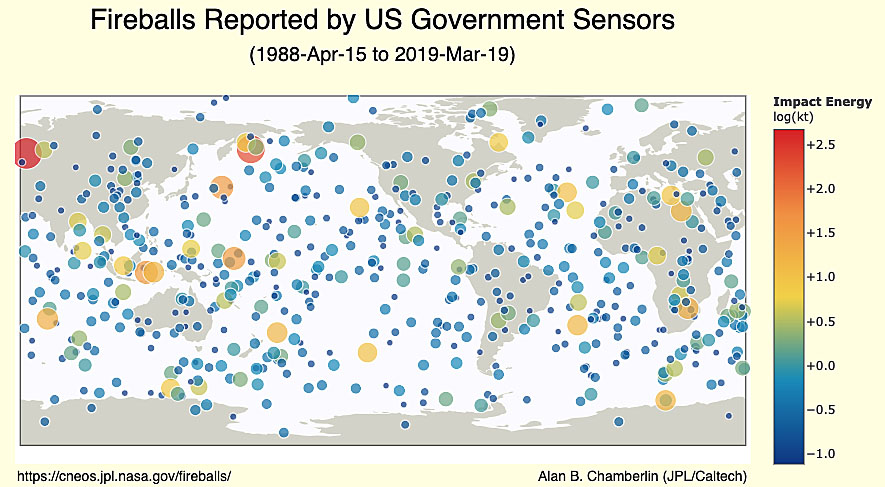

Astronomers have discovered more than 90% of near-Earth asteroids larger than a kilometer across — the ones that would have serious consequences in the event of a strike. But little ones, like Chelyabinsk or Tunguska? Nearly all are unannounced simply because they're so tiny, they escape our notice. Fortunately, the atmosphere serves as an excellent defense against objects up to several tens of meters.

CC 1.0 / Wikipedia

You can always check on the most recent significant meteor blasts at NASA's Fireball and Bolide Data page, which also includes more details on the Bering Sea impact.

Much of a meteoroid's mass is shed as dust, some of which ultimately serves as nuclei for the formation of noctilucent clouds, pale blue clouds that glow just above the northern horizon at the end evening twilight in summer. In this way, such dramatic and potentially harmful events confirm Earth's cosmic connection every single day.

14

14

Comments

cjdaniel

March 21, 2019 at 11:29 am

The second image ("single frame from Himawari 8") does not show the "truncated glowing meteor." The visible "orange" bit is the trail (which was nearly vertical) and the thing marked in this article as the "dust trail" is its shadow on the clouds. As evidence, please consider the fact that shadow of the dust trail moves with the changing sun angle in the later frames from Himawari 8.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 21, 2019 at 11:58 am

Hi CJ,

At first, I thought that too. But the single image is one frame grab from the animation. In the animation, you can watch the dust trail (dark streak) twist, change shape and expand into a large, diffuse cloud over the sequence. You would expect a nearly straight-line trail of dust from an incoming meteoroid before air currents and turbulence altered its shape — exactly as shown in the sequence. You can also see the glowing meteor trail within the dust trail almost concurrent with its formation. If the streak were a shadow, it wouldn't twist and expand into a puffy dark cloud. Finally, the photos were taken over many minutes of time. I checked the frame rate for Himawari and it's one frame every 10 minutes. A meteoroid's flight through atmosphere is measured in seconds. A shadow would not linger once its source disappears from the scene. I even wonder whether something that small (about 35 feet across) would cast a noticeable shadow at the scale of the photograph.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

hoehneb

March 21, 2019 at 12:42 pm

Bob,

I'm with cjdaniel on this. The dark patch is not dust, but a shadow of a cloud that is difficult to see because it is roughly the same brightness and color as the clouds behind it. If you look closely, however, you can see the white cloud against the lower clouds. The shadow- which is is the same dimension of the cloud perpendicular to the sunlight- stretches out as the terminator moves over the course of the animation.

The meteorite itself would not cast a shadow- and, indeed, would be far too small to be seen a single image.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 21, 2019 at 12:57 pm

Hi H,

Great discussion here. If a shadow of a cloud then how would you explain the briefly visible orange meteor glow embedded within it? There are also many similar shaped white clouds streaming below that do not cast shadows.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

hoehneb

March 21, 2019 at 1:15 pm

First, a glowing cloud would still cast a shadow. Second, the cloud is being illuminated side-long by light that has been attenuated and reddened (the event occurs near local sunset). The dusty cloud itself attenuates blue light and produces a red-fringed shadow.

The clouds beneath do, in fact, have shadows, they are simply not as long since they are all on the same level and there isn't much vertical relief.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 21, 2019 at 2:15 pm

H,

The event occurred at 11:48 a.m. local time. Sunset would have been around 3:30 p.m. on that date at that latitude. Also the orange in the cloud is distinct and not visible on any other clouds. If it were a shadow how could it have any color at all? I do see that white cloud rising at the end which makes me curious, but it may be unrelated to the argument you put forward for the streak. Also, there is the other image from the Terra satellite to consider. It was taken from a very different angle yet also shows the streak.

PS. I do notice some dark streaks in the distance moving along nearer the terminator, which again makes me curious, but their behavior is different. The move downward and disappear.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

StanR

March 23, 2019 at 10:22 am

I too am with cjdaniel and hoehneb on this. Holding a pencil, oriented towards 10:30, just under the orange, my eye can follow that orange through the animation as its color fades, and it smoothly becomes visible as a noctilucent cloud against the dark background. The dark streak moves more toward 12:00 in the animation. I think the dark is a shadow, later appearing to twist and expand as the setting sun causes the projection to rise in the atmosphere, projected onto a pretty solid cloud bank in the first frames, but projected into some higher level semi-transparent haze by sunset. It also seems to "move" faster toward the end, which a shadow would do as the sun sets.

Beautiful pictures and a very interesting discussion, nonetheless.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

hoehneb

March 21, 2019 at 1:17 pm

Look at how the shadow stretches out in the last few frames. Then look at how the cloud is now visible against the dark background, against the cloudtops where the sun has set.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

dilo

March 23, 2019 at 6:45 am

Dark trail is a shadow for sure. But, if you look carefully to the very first frames of animation, you will see two dark clouds slowly moving to West BEFORE appareance of orange plume and its shadow! I suspect they could arise from meteor first entry in high atmosphere, but I am not sure because I do not know images timing…

Marco

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 23, 2019 at 10:26 am

Hi Dilo,

That's tough to see, but I agree now that we're seeing shadows. If you look closely however you'll see a good deal of meteoroid dust (orange color) mixed in with the streak. I'll post a new photo showing this in a minute.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 23, 2019 at 10:23 am

Hi Brad,

I've looked at more images and I now think you are correct. It's primarily a shadow but there's a good deal of meteoroid dust mingled within. The Terra images make this much more apparent. So I want to thank you for pointing this out and for our discussion. I'll post new photos soon that show how dust and shadow overlap.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

March 21, 2019 at 3:08 pm

"Japan's Himawari 8 weather satellite" I would ask if some of these questions arise from folks who consider Himawari 8 satellite a hoax, thus we live on a flat planet that does not spin.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lfulham

March 22, 2019 at 6:22 pm

Enjoying this article, I note the comment re bifurcation of the trail and wonder if that may be part of a common structure of meteor trails with vortex formation in the wake of the physical object. Such a trail is shown in the image:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/130gt/33568468448/

In the same way as a spherical planetary nebula looks ring like, a long cylinder of glowing gas could appear as two parallel lines

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

March 23, 2019 at 10:24 am

Hi Len,

Beautiful photos! Thank you for sharing the link.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.