The near-Earth asteroid constantly shoots out rocks, leaving planetary scientists perplexed.

The asteroid 101955 Bennu is spitting at us, and we don’t know why.

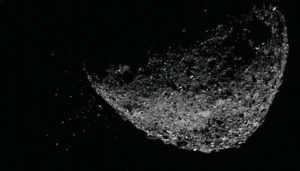

D. S. Lauretta et al. / Science 2019

The spittle takes the form of centimeter-size bits of rock shooting irregularly out from the asteroid’s surface. Some rocks spew forth roughly 100 at a time; others come in batches of a dozen or so. Still others launch as solitary particles. Although many of these pebbles escape forever, others orbit for hours or days before landing again, creating a tiny swarm around the asteroid.

Osiris-REX team member Carl Hergenrother (University of Arizona) discovered the activity in early January 2019, when flicking through backlogged images from the spacecraft’s optical navigation camera. Back in 2005 when he’d first proposed Bennu as the target for NASA’s sample-return asteroid mission, he’d argued that the body might be active — it had a similar appearance to the near-Earth asteroid 3200 Phaethon, which coughs out tens of thousands of kilograms of material each time it comes close to the Sun.

But no one expected anything like this.

After recovering from their initial astonishment and checking that the little bullets weren’t a danger to the Osiris-REX spacecraft, the team amped up its imaging through January to mid-February, ultimately catching nearly 40 outbursts that ranged from tiny explosions of 70 or more shards down to individual particle escapees.

The team announced the surprise discovery in March, but beyond a suspicion that the activity might, like Phaethon’s, be tied to Bennu heating up during its annual close approach to the Sun, the researchers didn’t know what to make of it. Now, in the December 6th Science, mission principal investigator Dante Lauretta (also University of Arizona), Hergenrother, and their colleagues report their analysis of the three largest events and a handful of individual ones from the January/February period to try to figure out what’s afoot. The short answer: we still don’t know.

The team considered a range of options and discounted several, including the ice vaporization that we’re familiar with from comets (Bennu doesn’t seem to have the requisite ice deposits, nor any cometary plumes). They settled on three possibilities: water molecules liberated from minerals by grinding, cracking, and heating sublimate, propelling grains off the surface*; meteoroid impacts; and thermal fracturing.

Bennu rotates every 4.3 hours, which means that every 4.3 hours its airless surface experiences a temperature rollercoaster, plunging to 250 kelvin at night and surging to 400 K just after local noon. This dramatic cycling can cause rocks to crack and crumble — in fact, data from the Japanese Hayabusa 2 spacecraft, which just left its own asteroid target, Ryugu, indicate that more than half of the cracks on Ryugu’s surface line up north-south, as you’d expect if they formed as the rocks repeatedly rotated into darkness and light.

The three largest events explored in the paper, on January 6th, January 19th, and February 11th, all happened during local afternoon at the sites they launched from. This makes sense if the cause is thermal fracturing, because it takes roughly three hours for heat to penetrate the rock’s upper couple of centimeters, creating a big difference in temperature that would stress the rock.

But the other events happened at random times, even at night. Plus, although the paper only includes data from January and February, the team has continued to watch since then, detecting a total of a few dozen or so outbursts — even through Bennu’s aphelion, when it’s farthest from the Sun. Only the major events happen during local afternoon. The range in timing suggests that more than one mechanism may be at work.

“What’s really interesting about this discovery is that it’s very possible this happens on all asteroids, and it just hasn’t been seen yet,” Hergenrother says. No other spacecraft has huddled as close to an asteroid for as long as Osiris-REX has — even Hayabusa 2 only did short excursions close to Ryugu’s surface, and it also didn’t have a sensitive enough camera to see such activity.

Reference: D. S. Lauretta et al. “Episodes of particle ejection from the surface of the active asteroid (101955) Bennu.” Science. December 6, 2019.

*Correction: The original version of this text said that it was the water molecules' liberation from minerals that propelled the grains, not the water's sublimation (which comes after liberation).

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.