Comet Borrelly's nucleus, as recorded by Deep Space 1 on September 22, 2001. Details as small as 50 meters can be resolved on the 8-kilometer-long object. The nucleus is actually very black, so contrast has been enhanced here.

Courtesy NASA/JPL.

Scientific intuition tells us that a comet's nucleus should be a frozen mountain of ice and dust. But that's not what Deep Space 1 discovered when it flew past Comet 19P/Borrelly last year. A recently released analysis of spacecraft spectra finds that Borrelly's "icy heart" exhibits no trace of water ice or any water-bearing minerals. Moreover, the nucleus is actually quite hot — ranging from 300° to 345° Kelvin (80° to 160° F).

What this means, according to Laurence Soderblom (U.S. Geological Survey), who led the analysis team, is that virtually all of the comet's surface has become inactive — ice is present on too little of it to be detected spectroscopically. As further evidence, Soderblom notes that gas and dust appear to be escaping only from localized jets totaling less than 10 percent of the surface seen by the spacecraft. Ground-based observations also show Borrelly to be a weak producer of gas and dust, typically releasing less than a ton of water per second. Because this comet has been trapped in a 7-year-long orbit around the Sun for at least two centuries, scientists believe it has exhausted most of the volatile consituents needed to create an impressive coma and tail.

Deep Space 1's spectra weren't entirely featureless: the comet's inky black nucleus exhibits an unexplained absorption at 3.29 microns. Soderblom guesses that this might be the signature of polyoxymethylene (a chained polymer of formaldehyde, H

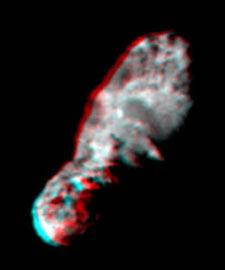

By combining two frames taken a few seconds apart by Deep Space 1 as it swept past Comet Borrelly, mission scientists have created this stereo image. Use anaglyphic (red-blue) glasses to view it in three dimensions. The elongated nucleus has a kink near its center, and the half at lower left juts prominently in the camera's direction.

Courtesy Laurence Soderblom (USGS) and NASA/JPL.

Mission scientists are thrilled to have any spectra at all to work with. Just as it passed 2,170 kilometers from the comet last September 22nd, Deep Space 1 scored a direct hit with its camera-spectrometer, recording 45 scans across the 8-km-long nucleus. And because only a handful of tightly collimated jets were spewing into space, the spacecraft had a clear sightline through the inner coma. The resulting images record features on the nucleus as small as 48 meters — far more detailed than the views of Comet Halley returned by the Giotto and Vega spacecraft in 1986.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.