Scientists were able to use space-based observations to find high carbon concentrations in Comet ISON before its untimely demise.

Disappointing highest hopes and frustrating skygazers around the Northern Hemisphere, Comet ISON did not survive perihelion. But the comet’s untimely death didn’t prevent scientists from studying it. In an American Geophysical Union (AGU) press conference last week, an international panel of scientists representing several different spacecraft reported preliminary scientific results from observations of the now-defunct comet. It turns out ISON was much smaller than previously believed and had a surprising amount of carbon.

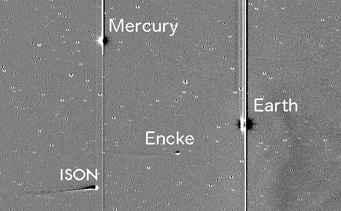

ISON, Encke, Mercury, and Earth as seen by NASA's STEREO-A spacecraft.

Karl Battams / NRL / NASA-CIOC

Since Russian amateur astronomers first spotted the comet in 2012, zooming in from the distant Oort Cloud that surrounds our solar system, scientists have been speculating about its size. Up until its demise, they had estimated its diameter at a couple of kilometers. But Alfred McEwen (University of Arizona) reported that an analysis of observations taken by the HiRISE instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter during the comet’s Mars flyby now suggests the diameter was between 100 and 1,000 meters. HiRISE couldn't resolve the nucleus from its distance, but its albedo measurements suggest that the size of the dirty ice ball lay in the middle of that range, around 600m.

HiRISE wasn’t the only well-placed spacecraft that caught ISON on its way in. Due to a happy accident, the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft, currently in orbit around Mercury, was in the right place at the right time to study both ISON and Comet Encke as they passed through the inner solar system. MESSENGER performed about 9,000 spectral scans of ISON. Most of those data are still onboard the spacecraft, awaiting download and analysis, but the data downloaded so far indicates a large amount of carbon (both CO and C+) compared to Encke, which might suggest the presence of organic grains in ISON. These element species are usually fragile, so scientists don’t see much of them in periodic comets — like Encke — because they burn away during passages near the Sun.

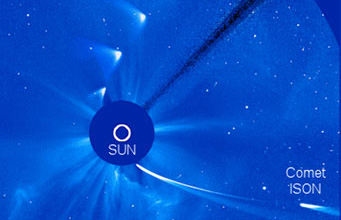

NASA / SOHO Consortium

With the new data, scientists confirmed the comet stopped expelling dust at perihelion, even though it briefly brightened afterwards. One theory for this unexpected brightening is that when the comet rounded the Sun it was pulled apart like a Slinky, with its pieces separated but still travelling together as a cloud of debris. That separation would have increased the surface area reflecting sunlight, creating the illusion that the nucleus was brightening.

While it’s unclear how or why some sungrazers survive perihelion and others don’t, the consensus is that Comet ISON was too small, too volatile, and too new to survive a close encounter with our star.

Emily Poore, Sky & Telescope's editorial intern, has a B.A. in physics and English literature, and is working on her M.A. in publishing and writing at Emerson College.

2

2

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

December 17, 2013 at 12:49 pm

Thanks for this interesting and timely postmortem report. A couple of lessons I'm taking from the Comet ISON story: 1) Predicting the behavior of a new comet is a fool's errand. The amount of ISON hype in the amateur astronomy press and online forums has been embarrassing. 2) Robots in space are able to do more and more, including observations that are wildly different from their primary missions. A couple of planetary probes happened to be in the right place at the right time and were able to analyze a passing comet better than any instruments on Earth. And our fleet of solar space telescopes caught ISON's final days and moments. It makes more sense to invest our limited space exploration budgets into many robots that can be in space for a long time than in one or a few brief human missions, even if the human missions would be more telegenic.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andy Briggs

December 21, 2013 at 5:53 am

ISON was another 1973 Kahoutek all over again (which I did manage to see....in binocular). We all get excited at the prospect of a bright comet, but the astronomical community really needs to rein in the hype. If comet research has taught us anything over the last few decades, it's that each comet is unique, unpredictable and rarely follows a predicted brightness curve. But we never seem to learn this lesson.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.