NASA's newest rover is finding ample evidence that the floor of Gale crater was once inundated with water.

Curiosity used the Mars Hand Lens Imager at the end of its robotic arm to record this 55-image self-portrait amid an area called "Rocknest Wind Drift" on October 31, 2012 — the 84th Martian day, or sol, of its mission. The rover's robotic arm is not visible because MAHLI is on the turret at the end of the arm. At upper right is Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), the rover's ultimate destination. Click here for a larger, annotated view.

NASA / JPL / MSSS

The 44th annual Lunar & Planetary Science Conference, which attracts nearly 2,000 solar-system researchers to Texas each March, is drawing to a close. There's been plenty of buzz — three oral sessions and five sets of posters — about early results from Curiosity, a.k.a NASA's Mars Science Laboratory.

It's been just over six months since the beefy rover plopped onto the floor of Gale crater, and even though the craft has only traveled about 500 meters (less than 2,000 feet), it's already got quite a story to tell. With its various hardware tests and instrument checks long since completed, Curiosity has made a solid case that the sprawling crater floor was once soaking wet — and probably more than once.

A few weeks ago, the rover drilled into a fine-grained mudstone and then delivered a powdered sample to two diagnostic instruments housed inside its chassis. Those analyses show that the rock contains a suite of elements in clay minerals — sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and carbon — that, together with water, would make a brew quite suitable for life.

A small rock nicknamed Tintina broke apart when Curiosity drove over it on January 17, 2013. Inside is a fresh, bright white surface that might be the same as bright hydrated minerals forming veins in the nearby bedrock of the "Yellowknife Bay" area. The rock measures roughly 1.2 by 1.6 inches (3 by 4 cm). This raw image was intentionally dark so that the rock's interior texture would not be saturated in brightness. Click here for a larger version.

NASA / JPL / MSSS

Later, it found that cracks between rocks in the surrounding terrain are filled with hydrated minerals, which formed in the presence of water. These compounds are obvious in infrared images taken by the rover's Mast Cameras, and its Russian-built Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument is sensing the presence of hydrogen (in water-derived hydroxyl, or OH, ions) beneath the rover as it trundles along.

In fact, Curiosity is finding good science even in its "oops" moments. Back in January the 1-ton rover drove over a small rock dubbed Tintina, which cracked open to reveal a startlingly white interior. It's full of hydrated minerals too.

As it's rolled along, Curiosity has been heading slightly downhill, a drop of some 65 feet (20 m) in all, and that gradual descent has taken it through a changing geologic landscape.

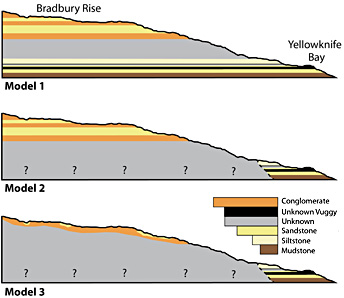

During its first six months on Mars, the rover Curiosity descended in elevation roughly 65 feet (20 m). Along the way it encountered several kinds of rock — but the area's underlying stratigraphy remains uncertain, as these three possible models suggest. Click on the image for a larger version.

Katie Stack & others

Whereas the rocks near its touchdown site at Bradbury Landing were loose conglomerates of pebbles rounded in ancient streambeds, the lower elevations exhibit thin, platy layers of sandstone and mudstone. These latter areas were where the rover first drilled into a rock about a month ago.

Curiosity's progress was briefly slowed in late February and mid-March by electronic glitches, but those have been resolved. Now, with Mars nearing a close conjunction with the Sun on April 17th, the mission's engineers will stop beaming commands to the rover for 2½ weeks centered on that date and also reduce the telemetry being radioed to Earth.

After conjunction, the science team wants to have another hole drilled and its contents tested. Then, barring discoveries that justify lingering in the area longer, project scientist John Grotzinger says Curiosity will "hit the road to Mount Sharp" — the rover's primary objective.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.